Glencairn Museum News | Number 7, 2016

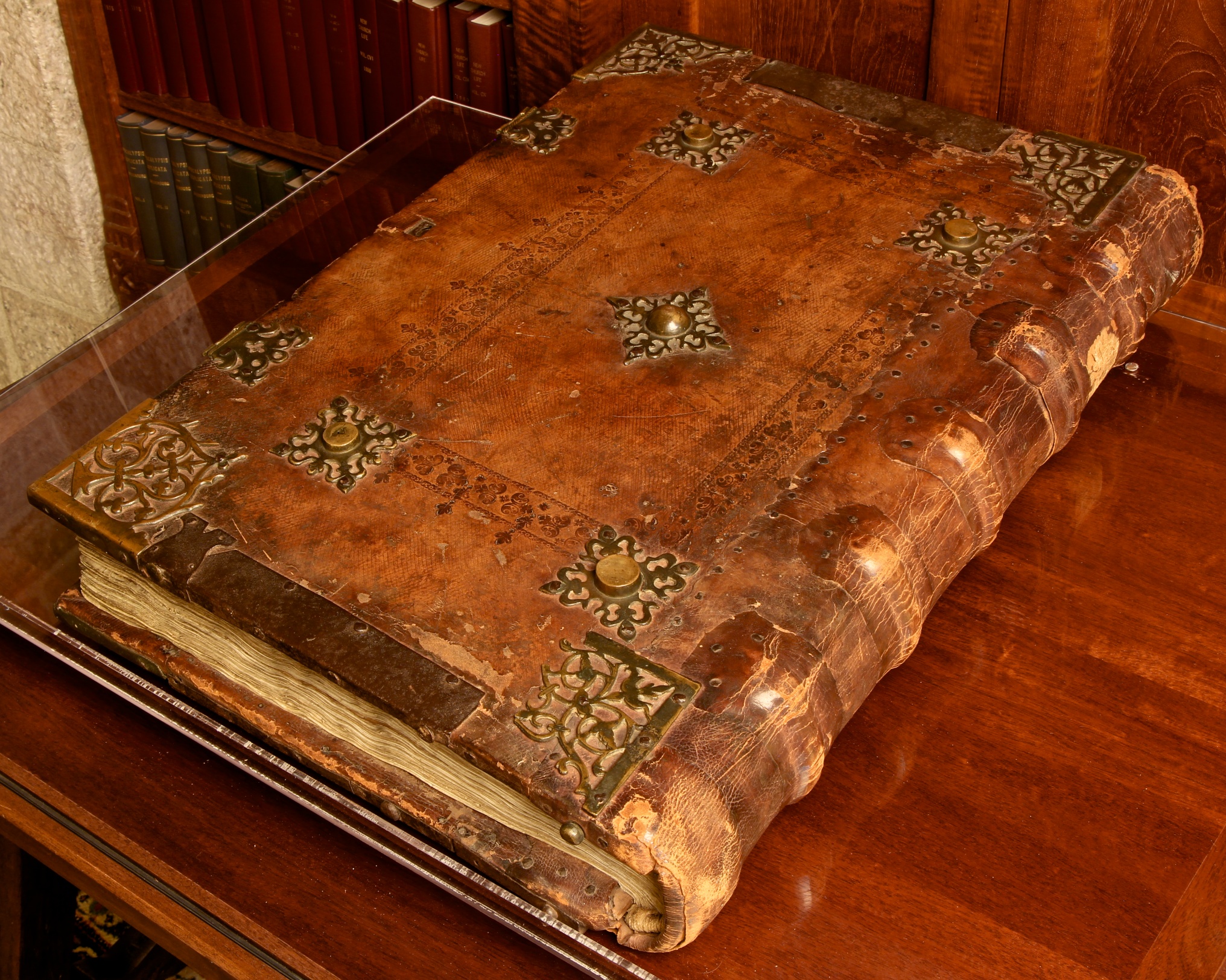

Figure 1: The cover and binding of Glencairn Museum’s manuscript 07.MS.778 showing the binding, metalwork, and tooled leather.

Keeping company with statues and stained glass, the book of plainchant filed as 07.MS.778 is unique among the collections at Glencairn for the mixture of art forms that it represents. Along with a few orphan pages from other sources, this 460-year-old, 157-page music book represents an intersection between sound and sight, between tool and artwork.

As a work of art, the manuscript is the result of significant effort by its makers. The pages are over two feet tall (75cm) and made of vellum, which is a high-quality paper made out of stretched and scraped calfskin. Each page is filled with black noteheads on red lines, underlaid with calligraphic text. Songs and sections begin with decorative capital letters known as illuminations. The cover is of hefty wooden planks, covered in tooled leather and decorated metalwork. Like other manuscripts of its time and earlier, it would have been created by a team of bookmakers and scribes in a scriptorium, each monk or group of monks responsible for a particular type of work. This is an amount of care not uncommon in books made prior to the availability of cheap printing. Books themselves were labor-intensive and rare, and the effort required to make them by hand heightened their importance as treasured possessions. Beyond its functionality, this manuscript was meant to be beautiful.

Figure 2: An example of the inkwork from folio 38v showing an illuminated letter “S” using blue and red ink as well as red and black text and music notation. Beyond the musical function, this hymnal was intended as a valued possession and a work of art folio, although the illumination style is relatively modest compared to some of the lavish presentation manuscripts that were made; see Figure 3 for one example of a contrasting style.

As a musical tool, the manuscript occupies a different place than a book of music produced today would hold. Like a modern liturgical hymnal, it is a collection of the music required for religious services. This music was sung by monks at several services each day, and the reason for the large size of the book becomes apparent when one considers that the entire monastic choir was singing from the same copy (see Figure 3). Even at 3.5 times the size of the average modern hymnal, that seems a difficult undertaking. However, the monks were not strictly reading from the book—it served instead as a memory aid. Less in keeping with the highly-literate classical music tradition we know today, early forms of music notation bear more similarity to the modern pop tradition of writing the names of chords above the notes. Much of what we think of today as “Gregorian chant” existed as an aural tradition for several centuries before it was written down for the first time. Although this particular manuscript comes from a time when music notation was becoming commonplace and highly developed, it was created in a monastic tradition of singing that was primarily based on memory. It has been estimated that monks in Benedictine monasteries, where they sang around six hours a day, would have had around 80 hours of plainchant memorized.1

Figure 3: This illuminated letter “C” is from folio 151 of a breviary in the collection at the Getty Museum, thought to have been made around 1420 in northeastern Italy. It illustrates how a large group of monks would have sung from a single choirbook. Image courtesy of the Getty Museum's Open Content Policy.

The story of this book begins with the history of the Order of Calatrava. Medieval Spain was defined by the lengthy reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from the Moors who had invaded from Northern Africa in the early eighth century. In the twelfth century, the Knights Templar abandoned the fortress of Calatrava, expecting to be overrun. A group of Cistercian monks moved in and formed a military order, obeying the Cistercian rule, but with the added duties of defending Calatrava against the Moors. This order was recognized in 1164 and was central in the reconquest, growing in size, importance, and wealth. At their height, they held more border castles than any other Spanish order, and could contribute to the field around 2,000 knights.2 Like many military orders, after the eras of the Crusades they gradually transformed from an organization of militant monks into a powerful political interest made up of nobles and royalty. By the sixteenth century, the Order of Calatrava had strayed from its original religious and military purpose, with only a few establishments where brothers still kept the religious observances.

Figure 4: The illuminated letter “T” on folio 144v includes the name “Mata” as well as two mentions of the date 1556.

In 1556, a monk named Mata was putting the final touches on the manuscript that now resides in Glencairn Museum. His identity is recorded by working his name into five of the illuminations, one of which also contains the date 1556 (see Figure 4). Mata’s work is consistent and accounts for the illuminations up through folio 136. At this point the illuminator appears to change and the quality of the ink and of the illuminations deteriorates across the remaining twenty pages of the manuscript. The bulk of the book up until folio 136 represents a concerted project, possibly in honor of the order’s 400th anniversary.3

The original length is unknown, since the first surviving folio picks up in the middle of a piece and implies that the first part of the book is missing. The additions starting on folio 138 may mean that the project was presented before it was complete and required later additions, or may be the result of repair work. The pages are trimmed, which implies that the manuscript was re-bound at some point in its career.

Figure 5: One of several pieces of metalwork on the cover of the manuscript that appears to reference its connection to the Order of Calatrava. Note the similarity to Figure 6.

Figure 6: The emblem of the Order of Calatrava: a Greek cross with a fleur-de-lis at each point. Wikimedia Commons: http://ow.ly/zn3M302QylV

Although the Calatravans as an order did not place a great emphasis on music, the several worship services held daily included a sung office. The high amount of wear and tear on the manuscript, particularly with regard to chants performed more frequently (such as the “Te Deum”), implies that it saw regular use as a working book. There are vellum patches and sewn up tears, and the corners of many of the pages are worn and darkened by oils from the hands of those who turned them. The addition of hymns by later scribes, including six crammed in on the last page in much smaller notation, suggests that efforts were made to keep the manuscript relevant and add to or replace its contents. While we have no reason to doubt the Calatravan provenance, it is stated by a secondary source—written on the 1920s sale card—and not confirmed by any evidence yet found in the book. However, there is one piece of evidence on the book that supports the connection: the metal decoration on the center of the cover bears a strong resemblance to the cross emblem of the Order of Calatrava. Although their significance waned after the fifteenth century, the last dissolution of Calatravan property did not take place until 1838. Then, or at some point prior, this manuscript probably fell into state or private hands. The first time it appears in modern sources is as a gift from Spain in 1926 for the Sesquicentennial celebration of the United States. It was then offered for sale through John Wanamaker’s store and purchased by the Reverend Theodore Pitcairn in 1927. In the 1950s, Rev. Pitcairn gifted the manuscript to the composer Richard Yardumian to serve as inspiration in his workshop, and it was given to Glencairn Museum by his widow, Ruth, on August 4, 1986.4

Figure 7: On the left is an example of a capital letter that was never illuminated, and on the right a more cramped copying job with a different style of illumination. This opening shows folios 156v-157 at the end of the book.

The music contained in this manuscript is not unique: it had been sung for hundreds of years before being copied in 1556 and is still sung today in some monasteries and Catholic churches that hold traditional services. This book can be likened to an intense game of whisper-down-the-lane, involving aspects of hand copying and memory, combatted by a Vatican that had for many centuries been trying to enforce the uniformity of how sacred music was being sung across the Catholic empire. The music being written in 1556 was part of the high polyphonic renaissance, and bears little resemblance to the unison plainchant contained in this manuscript. In more decadent churches, many of the antiphons were being sung to more recent music, but in the austere setting of a Calatravan monastery, the plainchant continued to be used. Thus it is that we have a book of medieval music created in the Renaissance.

The first 26 surviving pages contain nine settings of Psalm 95, the invitatory psalm for Matins. These are followed by 38 antiphons and responsories for the hours of Matins, Lauds, and Vespers. Folios 54-59 contain the lengthy hymn “Te Deum,” sung at the end of Matins services through most of the year. The remainder of the manuscript is filled with hymns. There are ten pairs for Matins and Lauds, followed by a section of special hymns to celebrate festival services, with 63 in the polished section of the book, and 33 additional hymns added by other scribes. This adds up to a total of 164 pieces of plainchant in the book as it survives today. The 116 hymns are strophic, which means that there are multiple verses to the same music. Unlike the other music in the manuscript, which is through-composed, the hymns show music only for the first verse, and then continue as text only. If opened to a page in the middle of a long hymn, it would not be apparent that the book contained music at all. In support of the notation’s use as a memory aid, many of the hymns require a page turn to reach subsequent verses when the melody would no longer be visible. In addition, from page 136 onward, the first line of music is given to remind the singer of the tune, but the rest of the music is not even included.

Figure 8: Most of the manuscript is dedicated to hymns where the chant is notated with the first verse, and subsequent verses are written without repeating the music. Folios 126v-127 show the last three verses of “Eterna Christi munera” as well as the first three verses of “Deus tuorum militum.” As is evident, the singers would need to have the melody memorized before turning the page to the later verses. Note also the vellum patch on the lower right corner, showing the wear and tear of a book that was in regular use.

Three large illuminations show the importance of different sections of the book, using not only the red and blue inks seen elsewhere, but also a green ink and gold highlighting. These are four times the size of the other illuminations and decorate the first letter of the “Te Deum,” of the first item in the hymn section, and of the hymn “Exultet celum laudibus.” The “Te Deum” and several of the later hymns are on folios with vellum tabs sewn on for ease of access. The unexpected focus on “Exultet celum laudibus” is intriguing, with both a tab and a large illumination that isn’t justified by its place at the start of a section. This is the hymn for the feast day of St. James the Just, and perhaps contains a clue as to the provenance of the manuscript.

Figure 9: One of the three large illuminated letters that show the height of artistic detail in this manuscript, the “V” on folio 59v begins the section of hymns.

07.MS.778 is an important part of Glencairn’s collection, displaying not only the art of bookmaking and illumination, but also serving as an artifact of the performance of music in the historic church, an ephemeral sacred art that nonetheless featured centrally in monastic life. Although there are many earlier sources of the music it contains, this manuscript tells a story of the continuing use of sacred music that may become more detailed as research continues.

Figure 10: Members of the ensemble Les Canards Chantants perform from the manuscript during one of their concerts as Ensemble in Residence at Glencairn. From left to right: Graham Bier, Alex Nishibun, and Owen McIntosh. Photo by Frank Slezak.

Figure 11: The hymn “Urbs Jerusalem beata” in modern notation with each verse underlaid. This is the piece featured in the YouTube video above. Edition by Graham Bier.

Graham Troeger Bier, PhD

Adjunct in Music, Bryn Athyn College

Director of Music, Bryn Athyn Cathedral

Music Director, Reading Choral Society

Endnotes

1 Anna Maria Busse Berger, Medieval Music and the Art of Memory, Berkeley: University of California Press: 2005, p. 49.

2 A. J. Forey, “The Military Orders and the Spanish Reconquest in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries,” Traditio, Vol. 40 (1984), pp. 197-234.

3 Carla Zecher mentions this possibility in her unpublished notes on the manuscript, written in August 1986 and held by Glencairn Museum.

4 Ruth Yardumian’s notes connected to her gift are held by Glencairn Museum.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.