Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2017

Crispin Paine at Stonehenge, a prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England.

Religion in Museums: Global and Interdisciplinary Perspectives is divided into six sections: “Museum Buildings”; “Objects, Museums, Religions”; “Responses to Objects, Museums, and Religions”; “Museum Collecting and Research”; “Museum Interpretation of Religion and Religious Objects”; and “Presenting Religion in a Variety of Museums.” According to Marcia Brennan, Professor of Art History and Religion at Rice University, “This project engages the fascinating—and culturally important—conjunction of the subjects of museums and religion. The book has the potential to address and shape the future of this interdisciplinary discourse through an intriguing conjunction of cultural, scholarly, and curatorial perspectives.”

You are one of the editors of the new book, Religion in Museums: Global and Interdisciplinary Perspectives (published by Bloomsbury Academic, London/New York). Why this book, and why now?

Things have changed hugely in the last ten or more years. In 2004 Sullivan and Edwards edited Stewards of the Sacred; in 2000 I edited Godly Things: Museums, Objects and Religion. Both books found museums largely ignoring religion. But since then very many museums have begun taking religion seriously, and there have been some major exhibitions, even in quite conservative art museums, directly addressing the topic. And there have been a good number of books (including some important ones in German and Italian) both on the topic generally, and on Catholicism and museums, Islam and museums, and Buddhism and museums.

Meanwhile religion has grown stronger and stronger in much of the world. The movement of people has meant more and more of us live beside people of other faiths. And religion has taken on a key role in the world’s politics. So we thought the time was right to look at the whole topic of religion in museums again, point out some of the issues, and have a shot at peering into the future.

For many years, the religious dimensions of objects in museums—especially art museums—were deemphasized, sometimes out of a fear of creating controversy. Should museums make explicit the religious meaning of the objects in their care? If so, why?

Was it fear of controversy? Yes, I think perhaps it was. Religion is difficult—it lies at the heart of who we think we are, and how we understand the universe we live in.

But, yes, I do think museums should make explicit the meaning of their objects. Sometimes, of course, the emphasis of the exhibit will be on the object’s beauty, its recent history, what it is made of, and so forth. But always visitors should also be helped and encouraged to understand the religious significance of the object, both because they have a right to know, and because this may be a first step to a wider understanding of our faith, other people's faith, and faith itself.

Note, though, that a number of contributors to the book raise the question of traditions of restricted access. For example, what should Australian museums do about “sacred/secret” objects? As Samantha Hamilton, conservator in Melbourne, asks: “who has the authority to speak on the presentation and preservation of sacred materials?” (in “Sacred Objects and Conservation: The Changing Impact of Sacred Objects and Conservators.”) And we mustn’t forget those countries where a secular tradition feels itself under attack by militant religious groups. In India, for example, many people see museums as bastions of reason against unreason.

A modern home altar in the “New Age” tradition. In addition to a number of family photos, the altar includes objects from Buddhist, Catholic, Hindu, Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Tibetan and Chinese traditions. Photo: Crispin Paine.

To what extent should museums allow religious objects to “speak for themselves,” and to what extent should curators interpret them for the public? Should anyone outside the museum be involved in the interpretation process?

Maybe just because of my local history background, I don't really believe any object “speaks for itself.” Just by putting two objects in a case together the curator is interpreting them—in fact, by putting an object in a museum at all we are saying something about how we understand it. So if we are interpreting an object willy-nilly, let’s try to do the job as well as we can!

As for whom to consult, that can often be more difficult than it seems. I sometimes give the example of a family friend who has on her bedroom chest of drawers an “altar,” on which there’s a crucifix, an image of the Holy Trinity, figures of Guan Yin, Siva and Buddha, and family photographs. Each morning she lights incense and meditates in front of it. If one day my friend gives her Guan Yin statuette to a museum, who will the museum consult about it? The scholar may explain how the Indian male Boddhisattva, Avalokitesvara, changed into the Chinese goddess Guan Yin. The people at the local temple may explain Guan Yin’s role in their religion and culture. But only if the museum interviews my friend will we ever understand the special (and very 21st-century) meaning the figure took on under her care.

Does a curator’s own religious faith (or lack thereof) affect the experience of the religious objects in his or her care?

Such an interesting question! I firmly believe yes, and I can point to directors of big museums whose faith has turned around their museum’s attitude to religious objects. But I can’t prove anything at all—there’s a wonderful topic here for a PhD!

In Europe one can generally assume that most curators, like most museum visitors, have no faith, and very often have no understanding of what faith feels like inside. In the US—and much of the rest of the world—of course, it’s quite different.

Are there museums that allow—or even encourage—visitors to show devotion or relate in a religious way to objects in their galleries? How many museums consider this to be desirable?

Indeed there are. I feel there are two aspects. Firstly, there are any number of museums which double up as shrines, or which include shrines in their galleries. This is common in Buddhist Asia, but it’s found all over the world: look at the Father Michael J. McGivney Gallery and Reliquary in the Knights of Columbus Museum in New Haven, Connecticut. He was the founder of the Knights of Columbus, he’s being considered for sainthood by the Vatican, and his reliquary in the museum contains second-class relics obtained during the exhumation of his remains in 1981. Another bigger example (and even more political!) are the Relics of the Prophet in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul, Turkey. In what has been since 1923 a secular museum, the relics are nowadays honored by the Qur’an being read beside them, 24-hours-a-day.

A shrine containing relics of the Lord Buddha presented by the government of Thailand to the National Museum in Delhi, India. According to the museum’s website, “These objects are of great reverence to Buddhist pilgrims, and the Museum gets hundreds of visitors of Buddhist faith from all over the world who come to this room to pay homage and venerate the relics.” Photo: Crispin Paine.

Secondly, devotees are often going to insist on showing their devotion even if they are discouraged. The National Museum in New Delhi was given a relic of the Buddha by the Thai government; when I visited there was a notice beside it stating, “Offerings and Donations of Any Kind are Strictly Prohibited.” (What about prayers?) Many museums, though, are quite relaxed about the less assertive visitor behavior: flowers left by the image, people prostrating in front of it, and so on. Some museums do positively encourage it, inviting local religious groups to hold ceremonies in the gallery, and so on. Generally this is to draw in a more diverse audience, to encourage minority communities to feel at home in the museum. Another reason, of course, is to help all visitors to understand how the object is seen, understood and treated—a Hindu god-image feels very different when clothed and enshrined than when it stands naked on the museum plinth.

Mind, encouraging cult activities in the museum demands all sorts of compromises: not upsetting other visitors, and not breaking the conservation rules. I’ve yet to see an animal sacrifice in a museum gallery. . .

A number of the essays in the Religion in Museums book raise these questions. For example, Australian anthropologist Denis Byrne remarks, “With few exceptions, museum collections represent a dead-end street for religious objects. While devotees may visit them in custody, so to speak . . . for the most part their careers as sacra are over” (in “Museums, Religious Objects, and the Flourishing Realm of the Supernatural in Modern Asia”). He calls for devotees at least to be allowed to make offerings, pointing out that in popular Asian religion gods and spirits need the prayers, offerings and support of devotees.

How can museum buildings (i.e. the architecture) structure the visitor’s experience of the sacred?

Crucial—and the subject of the whole first section of the book. Gretchen Buggeln offers a chapter that directly addresses the question, outlining four different modes “in which museum architecture can operate to engage the transcendent or sacred: associative, magisterial, therapeutic, and redemptive” (in “Museum Architecture and the Sacred: Modes of Engagement”).

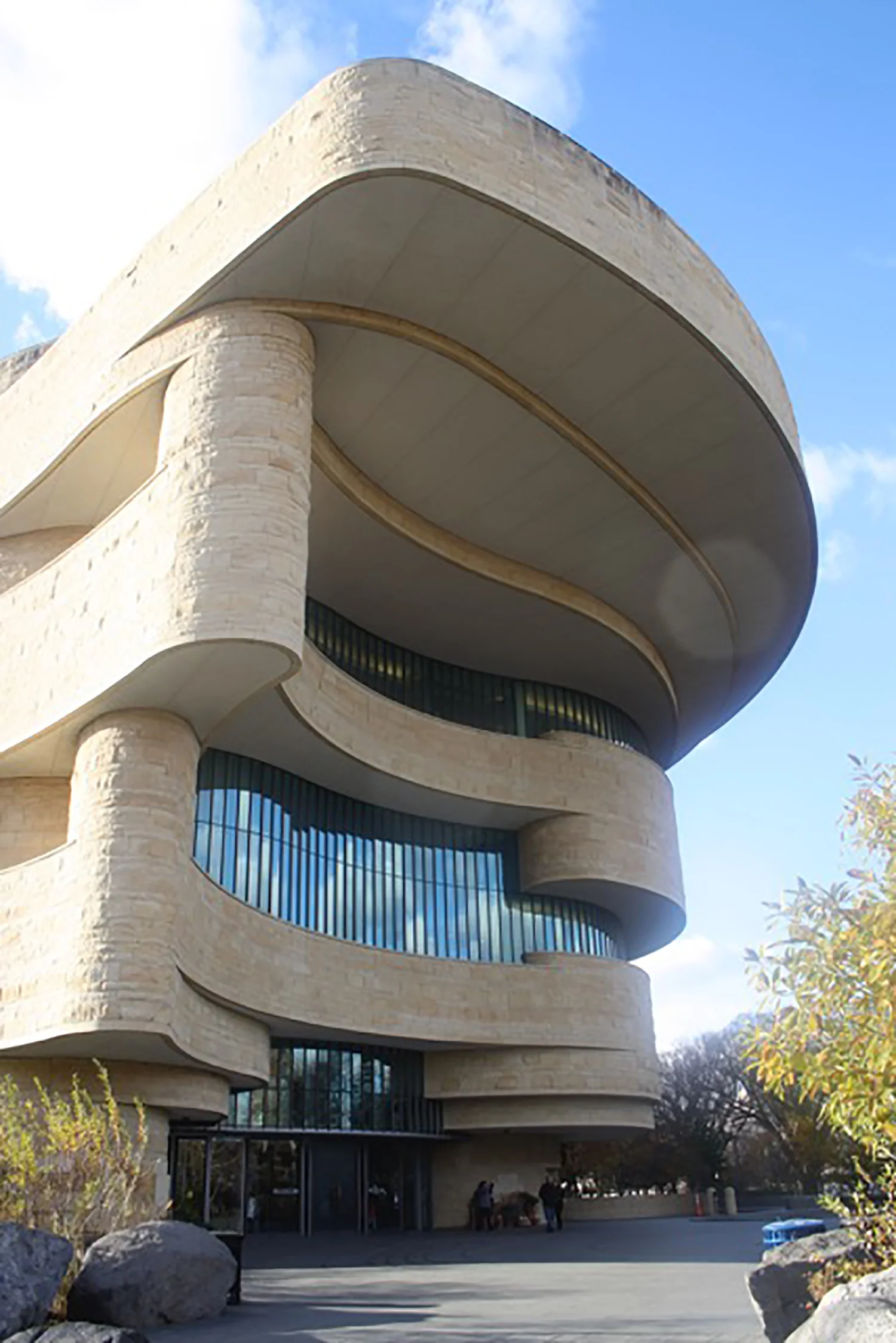

The book includes an interview with Douglas Cardinal, the architect of the Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC.

During the design phase of the building in the 1990s, the National Museum of the American Indian consulted with Native communities and individuals across the Western Hemisphere. According to the museum’s website, it was decided that “the building's design should make specific celestial references, such as an east-facing main entrance and a dome that opens to the sky. . . The building’s distinctive curvilinear form, evoking a wind-sculpted rock formation, grew out of this early work, forming the basis for the architecture.” Photo: Crispin Paine.

Recent trends in the museum profession indicate a growing consensus that museums should not be “neutral” places, but should seek to contribute to the betterment of society. What implications might this approach have for museums with religious objects?

I think this is precisely why museums have started to take religion so much more seriously. For the past generation society has asked two things of museums: that they provide entertainment and education to as wide a public as possible, and that they contribute to the promotion of harmony within the community. Museums with religious objects (surely that’s the great majority?) have a special opportunity to forge links with minority communities, and to help them to explain some, at least, of their culture and traditions to the public at large. We all need to understand each other, and though because I understand you it doesn’t mean I love you, at least it’s a first step!

You have visited Glencairn Museum yourself, and have included an essay about Glencairn in your latest book. Do you have any thoughts about how Glencairn is positioned in relation to other museums that exhibit and interpret religious objects?

Glencairn has a wonderful opportunity to offer an example to the handful of “religion” museums worldwide, but more importantly, to the museum movement as a whole. It has strong collections, but also it is small enough and flexible enough to take risks and do things differently. What’s more, it has a record of imaginative and successful exhibitions, events and outreach (Glencairn Museum News is an example!) that push the boundaries.

What might Glencairn Museum do in the future? We will all have our favorite ideas! Mine is an exhibition and associated events on the subject of religion in the classical world. We are all used to seeing ruined temples, statues of gods, and bas-reliefs of rituals. But perhaps we’re so used to seeing them that we don’t often pause to wonder how the ancients—outside the heroes in the epics—actually felt about their gods, whether they trusted the priests, believed in the auguries, actually made their sacrifices? I’m sure it would be possible to put on an exhibition that asked (at least) questions like these—and then went on to compare classical religion with modern-world practices and ideas. I would hope to see the emphasis on practice, what people actually did, and so what they felt, rather than on the familiar myths. I take it that is what Glencairn's curator Ed Gyllenhaal in the book calls understanding religion “from the inside” (in “Religion at Glencairn Museum: Past, Present, and Future”).

At the conclusion of the annual Sacred Arts Festival at Glencairn Museum, visitors are invited to participate in the ritual dismantling of a Tibetan sand mandala. Mandalas are an ancient art form of Tibetan Buddhism. Drawn in colored sand, they represent the world in its divine form, and serve as a map by which an ordinary human mind can be transformed into an enlightened mind.

Religion in Museums: Global and Interdisciplinary Perspectives (2017), published by Bloomsbury Academic, London/New York, was edited by Gretchen Buggeln, Crispin Paine, and S. Brent Plate. It can be ordered though Amazon.com.

(Interviewed by CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.