Glencairn Museum News | Number 2, 2019

Hex Signs: Sacred and Celestial Symbolism in Pennsylvania Dutch Barn Stars, an exhibition in Glencairn's Upper Hall.

Nestled in the rolling hills and valleys of southeastern Pennsylvania, a cultural treasure lies hidden in plain sight. Vibrant murals of stars, sunbursts, and moons painted in vivid colors punctuate the exteriors of the generously-proportioned barns of the Pennsylvania Dutch country in a manner that is unique among American artistic traditions. Complex, geometric, yet deceptively simple, these abstract representations of heavenly bodies once saturated the rural landscape, and now serve as cultural beacons of the robust and persistent presence of the Pennsylvania Dutch, who once settled and still maintain a strong presence in the region.

Figure 1: Weathered Barn Star, Windsor Castle, Berks County, ca. 1920.

Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, Gift of Bart Hill, Nephew of Milton Hill.

This restored sixteen-pointed star is one of a series from a barn in Windsor Castle, Berks County. Due to the star’s complexity, it was attributed to the work of the prolific barn star artist Milton Hill, who painted extensively in the immediate area. These stars were likely painted in the early twentieth century, but show patterns of highly pronounced relief, produced by the sun’s weathering of the wooden barn siding.

The residents of these quiet rural communities regard the stars as something to be cherished, yet perfectly ordinary—an agricultural expression of folk art, and as commonplace as eating pie. Nevertheless, for the outside world, the barn stars, also commonly called hex signs, have captured the American imagination as generations of visitors to the region marvel at the seamless integration of art into the agrarian countryside.

Just as humanity has marveled at the stars in the sky throughout history, and sought some sense of meaningful interpretation of their order and light, so too have these folk art depictions of the stars evoked a sense of wonder in all who behold them. For the Pennsylvania Dutch they are part of the fabric of life, but for those from outside of the community, the stars are thought to be representative of that which is otherworldly, mysterious, or supernatural.

Between these two different views, the history of the folk art barn stars has been the subject of debate for nearly a century, and is only now beginning to take shape yet again as Pennsylvanians in the present day not only rediscover the art form, but also strive to preserve their open spaces and agricultural communities. It is abundantly clear, however, that no matter how the stars have been celebrated, interpreted, commercialized, or appropriated throughout the centuries by inhabitants and visitors alike, their history is inextricably linked to the Pennsylvania barns themselves, and the Pennsylvania Dutch folk culture that built the barns, transformed the landscape, and continues to persevere in an ever-changing world.

Figure 2: A Classic Decorated Pennsylvania Barn, Albany Township, Berks County, ca. 1850, courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

The barn standing at the location of the old Ida Bond Hotel was last painted in the 1980s by Johnny and Eric Claypoole of Lenhartsville, Berks County. The barn is a classic mid-nineteenth century Pennsylvania barn, featuring arches over the doors, and four twelve-pointed stars across the barn’s forebay siding. No longer visible are three sets of arches over the windows, with three crosses within the arches.

A Survey of the Region

Although the decorated barns of the region have been photographed and documented in numerous waves over the years, beginning in the first half of the twentieth century,1 the landscape is in a state of constant change. Until recently, no comprehensive surveys of the region’s decorated barns had taken place since the 1950s,2 when the tradition was still very much in its hey-day and farming communities were substantially more stable. Due to rapid land development, suburbanization, changes in ownership, and economic circumstances, the range of visual expression in Pennsylvania barns of the region has diminished, leaving behind fragmented rural landscapes.

It was with these dramatic changes in mind that I embarked on a journey to comprehensively document all decorated barns in Berks and Lehigh counties—the heartland of the tradition—and to continue beyond the counties’ borders into Northern Montgomery, Northampton, Upper Bucks, Southern Schuylkill, Eastern Lebanon, and Northern Lancaster counties. As an artist myself, I felt compelled to document this cultural and artistic phenomenon before significant portions of the work were lost to memory.

Figure 3: Map of Southeastern Pennsylvania, Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Photos of Stars by Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Southeastern Pennsylvania is home to two distinct concentrations of barn decorations, defined by geographical features that separate the region. Star patterns are predominant along the Blue Mountain, part of the Appalachian Mountain Range bordering Berks, Northern Lehigh, and Schuylkill counties. Floral motifs are found throughout the Lehigh Valley, which spans Northampton, Lehigh, Bucks, and Montgomery counties. Barn stars are rarely found west of the Susquehanna, except for traditional wooden applique stars found in Bedford, Somerset, and Washington counties.

I set to work advocating for the support of a present-day survey of the region, and received research funding through the Peter Wentz Farmstead Society of Montgomery County, which awards the Albert T. and Elizabeth Gamon Scholarship to support studies in Pennsylvania Dutch culture. Although I had already started photographing barns as early as 2006, in the summer of 2008 I set out with atlases, and systematically drove every public road in Berks County to photograph and document the locations of decorated barns with original barn star paintings.3

Although I had expected to document an artistic tradition in decline—and that was precisely what I found in some areas—I was surprised and delighted to find that the sheer number of decorated barns in Berks alone had outstripped previous estimates for the whole region.4 I documented over 400 decorated barns in 2008 with the majority in Northern Berks, and have added scores from neighboring counties ever since, tallying over 500 for the total region. The epicenter of the barn star region is geographically located in Kutztown, with the overwhelming majority of the total tradition within a 30 mile radius.

Most surprising of all was the fact that these numbers continue to increase by as many as half a dozen barns a year, as active artists, such as Eric Claypoole of Lenhartsville, as well as property owners, continue to paint barn stars in the region. This is a sign of a healthy folk tradition, and one that is currently in no danger of disappearing from the landscape altogether. While the value of a survey is to create a snapshot in time, this survey has become a living record, including both the occasional loss of a historic barn, as well as the documentation of a living tradition that continues to shape the landscape in new and exciting ways.

Figure 4: A classic eight-pointed star, Albany Township, Berks County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

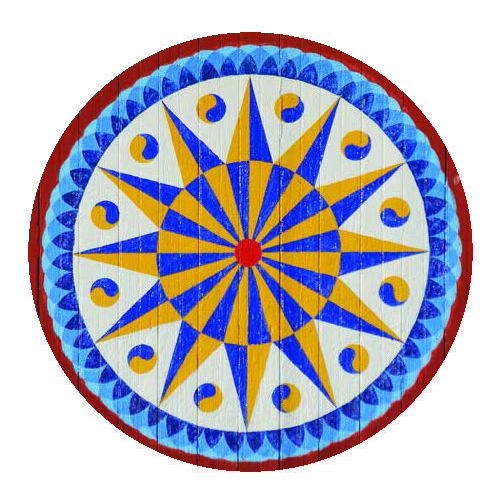

Figure 5: A Lehigh County star, including raindrop shapes and floral petal border characteristic of the region. Lower Macungie, Lehigh County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

As with all forms of research, an understanding of the barns was only possible through close cooperation with the cultural community of the Pennsylvania Dutch. As a native of Lebanon County, with roots in Berks, and as a speaker of the Pennsylvania Dutch language, my research is based not only in surveying the barns, but also in exploring the cultural memory of the region through oral histories, interviews, and other primary source documents, and continued dialog with the elders of the community and the families of property owners and artists. It is through this lens that the cultural significance and social history of the art form is best understood, and in doing so we can reach a better understanding of the folk culture of the Pennsylvania Dutch.

The Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch are the present-day descendants of several waves of German-speaking immigrants from central Europe beginning at the tail end of the seventeenth century, up until the time of the American Revolution, and shortly thereafter. These immigrants came from German-speaking regions of what is today Germany, including the Rhineland-Pfalz, Rhine-Hesse, and Baden Württemburg, as well as parts of Switzerland, Alsace, France, and as far east as Silesia in Poland and the Czech Republic.5

Fleeing the economic, social, and religious disruptions of perpetual warfare throughout the continent, these agrarian people departed Europe through the corridor of the Rhine River Valley, and arrived at ports in Philadelphia and New York before settling southeastern Pennsylvania. Upon their arrival in the New World, they were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the British Crown, and their English neighbors referred to them as “Dutchmen”—a word that originally applied to the broader family of German-speaking people from European territories.6

Figure 6: Twenty-Four Original Barn Stars, Surveys of Berks, Lehigh, Schuylkill, and Montgomery Counties. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Barn decorations exist in a wide diversity of forms, drawing upon celestial imagery blended with floral geometry. While the influence of specific artists can be clearly seen in certain communities, as a whole the entire region displays a broad range of patterns, colors, and proportions. Star patterns occur most commonly in eight, six, twelve, and four-pointed varieties, with numerous border styles and articulations between each point. Floral patterns combine lobed points, raindrop shapes in a variety of configurations, and borders suggesting the petals of a blossom.

Beginning with the founding of Germantown in 1683, and spreading throughout the region, the Pennsylvania Dutch settled much of what is today the counties of Berks, Lehigh, Schuylkill, Northampton, Northern Montgomery, Upper Bucks, Lancaster, Lebanon, and beyond. Their distinctive agriculture, religious expression, arts and architecture, industry, and trades, have shaped and been shaped by the broader American experience as these immigrants and their descendants migrated throughout the United States and into Southern Appalachia and the Shenandoah Valley, the Midwest and the Ozarks, the West Coast, and Ontario, Canada.

The majority of the Pennsylvania Dutch established communities organized around Lutheran and Reformed congregations. Only roughly four percent were members of sectarian groups, consisting of Anabaptist and Pietist Communities, including the plain communities of the Amish, the Mennonites, as well as the German Baptist Brethren and the Moravians. Around one percent were Roman Catholics.7

What originally unified them, in all their diverse creeds and places of origin, was the German language, spoken in a wide variety of distinctive dialects at the time of immigration. This coalesced into the spoken vernacular language of Deitsch, or Pennsylvania Dutch, a distinctive American hybrid that is similar in structure and sound to the Palatine dialects of High German today, along with an admixture of Swiss elements and English loan-words. Pennsylvania Dutch is spoken by over 400,000 people in North America today, and it is considered one of the fastest growing small minority languages in the United States, with the core of its speakers in the plain communities of the Old Order Amish and Mennonites.8

However distinct the plain communities may be in the American public imagination of today, these groups once formed only a relatively small portion of the Pennsylvania Dutch population, while the Lutheran and Reformed families who embraced American fashions and customs were the majority.9 It was from this broader cultural group that the tradition of decorated barns proceeds, culled from a vibrant past and rendered in colorful folk art expression into the present day.

Figure 7: An eight-pointed star within a star, characteristic of the Northern Berks-Lehigh border. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Figure 8: An eight-pointed star with raindrops between each star point, painted in the classic Lehigh Valley color scheme of red, white, and black. Upper Milford Township, Lehigh County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Art of the Barn

As a living tradition, barn star painters have graced the landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania with their artistic presence for centuries. No one knows who the first artists were and precisely when they began to paint stars on the wooden siding of Pennsylvania barns.10 They were likely farmers, carpenters, builders, and tradesmen who painted as a secondary occupation. Over time, their art inspired the classic arrangements of stars, painted arches, and decorative borders that characterize the rural landscape. Although the first artists kept no records of their work, wrote no firsthand accounts, and even their names are lost to the sands of time, their story is preserved in the nineteenth-century barns which still stand proudly throughout the region. Little did they know that their work would one day capture the interest of people across the United States, and come to symbolize Pennsylvania Dutch culture as a whole.

Large and bold enough to be seen from across fields and valleys, barn stars appear in series across the façades and gable ends of barns and outbuildings, serving as focal points in the farmscapes of the Pennsylvania Dutch. These elaborate geometric murals, when paired together with decorative painted trim, accent an otherwise quite ordinary agricultural structure, elevating it beyond mere utility to the level of folk art. Many of these designs are celestial, depicting sunbursts and geometric stars of varying numbers of points. Other designs are floral, featuring radial bursts of petals in organic patterns. These two types of motifs form the basic visual vocabulary of Pennsylvania’s barn decorations.

These classic geometric star patterns have been called a variety of names over the years, even within the predominantly Pennsylvania Dutch communities where the tradition originates.11 In the local vernacular, these motifs have been called Schtanne (stars), a term descriptive of their angular, radial forms as abstract, geometric representations of heavenly bodies. Another name in Pennsylvania Dutch is Blumme (flowers), suggesting the very same geometry that is also commonly found in the delicate blossoms of the terrestrial sphere. In keeping with this notion of plant geometry, barn decorations in this region also feature distinctive rain-drop shapes between each point of the radial patterns. These are combined in ways that suggest certain floral species, and were once occasionally called Lillye (lilies) or Dullebaane (tulips).12

Although these Pennsylvania Dutch terms predominated long before English terms were in common use, nevertheless the barn decorations are widely known as “hex signs”—an idea that did not originate among the folk, but first appeared in tourism literature of the early twentieth century.13 These outsider theories promoted the spurious claim that the stars served the sole purpose of protection from the supernatural. Although these accounts were highly imaginative and lacking any basis in fact, they were nevertheless some of the very first travelogues written about the decorated Pennsylvania barns, which served to introduce broad American audiences to the folk art of Pennsylvania.

Nevertheless, these stars of seemingly infinite variety, color, and form, tell an altogether different story of the vibrant artistic, agricultural, and spiritual traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Barn stars were not expressions of “superstition” as the tourist literature suggested, but abstract images of the heavens, refined by generations of artistic interest in geometry and agricultural interest in the stars. These beacons of celestial order and heralds of the annual progression of the seasons were once an essential part of the folk-cultural world view, and the inspiration for artistic expressions that permeated the material culture and architecture of Pennsylvania.14

Figure 9: An eight-pointed star with maltese cross pattern in the center. Jackson Township, Lebanon County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Figure 10: A twelve-pointed star recently restored by artist Eric Claypoole, with interlacing border and circular motifs between each star point, composed of two of the raindrop shapes common in the Lehigh Valley. Albany Township, Berks County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Figure 11: A four-pointed star from the Berks-Lehigh border with symmetrical arrangements of raindrops, suggesting the opening of a flower. District Township, Berks County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Sacred and Celestial Geometry

Paralleling the wide variety of barn star motifs and designs, there has been a diversity of associations and meanings for the various star patterns throughout the centuries. While artists and barn owners alike see the stars as alternately “decorative,” “representative,” “symbolic,” or all of the above, very few resist the idea that the star patterns have represented many different things throughout the generations. Just as humans throughout the ages have projected countless interpretations upon the orderly movements of the celestial sphere, so too have the artistic renderings of these celestial bodies on Pennsylvania barns been the subject of a wide variety of interpretations, theories, and organizing principles.

While some historic barn star painters resisted the idea that the star patterns had any inherent literal meaning, others embraced a very basic form of visual symbolism that parallels many aspects of the folk culture in Pennsylvania, as well as in Europe, where similar designs appear in folk art and architecture. Certain contemporary painters, such as Eric Claypoole of Lenhartsville, Berks County, draw upon oral history in the region to describe what the stars may represent numerically. On the most basic level, many associated meanings are based upon the number of star points or other visual elements. However, since the numbers do not have a single, fixed meaning, but are associated with a wide variety of concepts, the numerology of the barn star is also thought to express a wide variety of cosmological or religious ideas.

Figure 12: Historic Bucks County Barn, Photograph by Guy F. Reinert, ca. 1950, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

This barn once stood in Bucks County, near the border with Lehigh and Montgomery, and was painted by the prolific Noah Weiss (1842-1907), a hotel proprietor, wood carver, and folk artist of the Lehigh Valley. Weiss had no formal training, but was a master carver and painter, producing religious scenes of biblical stories for the walls of his hotel. He was also an innovative designer whose elaborate barn stars featured intricate raindrop patterns in radial formations that have become classic in the Lehigh Valley.

For instance, some have considered four-pointed figures to be expressions of the four seasons, or the cardinal points of the compass, while others have attributed the four-pointed star to the Christian concept of the cross. This alternately cosmological and religious significance of numbers is also applied to the pattern of the twelve-pointed star, which according to some is illustrative of the twelve months, and according to others is representative of the twelve apostles with a solid red circle in the center to symbolize Jesus Christ, while still others have compared the twelve points to the twelve tribes of Israel.15

Other examples of numerical significance that are religious in nature include the six-pointed star—as a symbol of the six biblical days of creation in Judeo-Christian tradition; the five-pointed star corresponding to the five wounds of Christ; the seven-pointed star representing the six days of creation plus the Sabbath day of rest; the nine-pointed star as the manifestation of the Holy Spirit in the nine “fruits of the spirit” in the Book of Galatians; and the eight-pointed star as a reference to resurrection, as Christ rose on the first day of the next week following his death, or the eighth day, signifying renewal and a new beginning.

Figure 13: Historic Lehigh County Barn, Photography by William Ferrell, ca. 1940, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

Once called “the most decorated” in the region, this barn is located in New Smithville, Lehigh County, close to the border with Berks. The front forebay wall features three pairs of six-pointed repeating star patterns. Each door and window is crowned with a star and a pair of moons. On each gable end, there is a triad of star patterns with a small star in a white triangle appearing to shine down from just under the pinnacle of the roof, as if the other stars were projections of its light.

These classic Christian interpretations of geometric figures are widespread in church liturgical symbols and architecture,16 but have never been uniformly accepted in their entirety as part of Pennsylvania’s folk culture. Protestant communities in early Pennsylvania deliberately avoided the continuation of Roman Catholic symbolic emblems, and only later accepted these ideas when Protestant churches in America intentionally reintegrated such liturgical elements during the Victorian gothic revival. However, these ideas certainly held some appeal among the Pennsylvania Dutch of the late nineteenth century, who treasured their highly ornamented Victorian family Bibles, and eventually replaced many of their small, austere meetinghouse churches with the rural and urban American equivalents of cathedrals.17

For barn star patterns, however, numerological religious meanings are complementary and are interwoven with cosmological significance, such as in the case of the number seven. The seven days of the week are not only a measurement of time specific to biblical literature, but are also connected with the seven visible planets of the ancients, who named the days of the week after these celestial bodies. Likewise, the number twelve is not only the number of the establishment of earthly spiritual authority and organization through the Apostles, it is also the number of the signs of the zodiac, the twelve-fold division of the solar year. In this same manner, the four-pointed star can symbolize the four elements and physical manifestation, and the eight-pointed star the cardinal and intermediate points of the compass, defined by the annual progression of the sun.18

Although many of the celestial patterns found on Pennsylvania barns have held countless symbolic associations over the centuries, their use as traditional decorative motifs has remained constant both in Europe and the New World.

Figure 14: The Barn at Grim Manor, Maxatawny Township, Berks County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

A classic Berks County arrangement of stars, painted trim, and decorative borders. Although the stars are not locally believed to serve a protective function, the three crosses above windows and doorways are not merely a decorative scheme, but a blessing of the structure.

The Decorated Pennsylvania Barn

It was once commonly believed that the barn stars first appeared on the landscape with the advent of commercially available ready-mixed paints and the widespread establishment of painting crews in the late nineteenth century.19 We know today that the earliest stars were painted generations prior, when paints were mixed by the artists from old recipes combining oils, pigments, and raw materials that were both locally available and imported for sale. Thus the availability of paint was never a limiting factor in the painting of barn stars, architectural elements, or decorated furniture.20

The Pennsylvania barn was the veritable canvas of agricultural expression. This distinctive architectural structure was unlike anything in the Old World, and is distinctly American in its evolution and form. Indigenous to Pennsylvania, yet informed by centuries of agricultural production, this barn was developed as a practical solution to the needs of a variety of immigrant groups farming the Pennsylvania countryside.

Drawing upon architectural traditions of Europe, eighteenth-century German and English-speaking immigrants from Central Europe and the British Isles had built a variety of barns in the fertile valleys of Pennsylvania before settling upon a New World form that revolutionized farming in early America.21 Standing separate from the home, the Pennsylvania barn was a two-level hybrid engineered for diversified farming operations. Banked into the gently sloping landscape, the lower level consisted of stables for dairy cows and draft horses, and the upper level was divided into bays or work areas dedicated to grain processing and storage, copious space for hay and straw, and the housing and loading of wagons.

This new Pennsylvania barn combined the distinctive cantilevered overhang, or forebay, of Swiss dairy barns, and the convenience of a banked, ramped access to the second story shared by both English and Swiss barns. These two identifying features—the forebay and the bank ramp—served to set the Pennsylvania barn apart from other types of barns in early America. The framing largely followed English patterns, but the form was distinctively Germanic, and often referred to early on as a “Swiss barn” or a “Pennsylvania German bank barn.”

As integrating features, barn stars are not simply decorations applied to the barn, but an important part of the overall architectural plan that visually connects and completes the appearance and function of the structure.

Figure 15: The Blümlisalp Chalet, constructed in 1571, in Aeschi, Canton Solothurn in Switzerland. A decorated folk-house, it bears sunburst and rosette patterns, as well as running borders, and the following inscription: “Highest Lord above us, with your graceful hand protect our house and village from sickness, storm, and fire, Amen.” And elsewhere on the same structure: “It is not in the field nor in the trees, but it must germinate in the heart, if one is to become better.” From Gilfian Maurer, Hausinschriften in Schweitzerland. Spiez: Verlag G. Maurer AG.

European Precedents

Considering the point of origin for the ancestors of the Pennsylvania Dutch, the Pfalz or Palatinate region provides surprisingly little or almost no direct correspondences, either in barn types or barn decorations, that compare to Pennsylvania. These European barns differ dramatically from the Pennsylvania barn and are typically neither banked into the earth nor equipped with a cantilevered overhang of the second story. The barns of the Palatinate are constructed largely of stone, and leave no large expanses of wooden siding upon which to decorate.22 Such barns are often connected structurally to the farmhouse as part of a courted farm complex or Hof, and clustered in small rural towns, rather than scattered throughout the landscape as in Pennsylvania. As a by-product of the medieval era, rural and urban spaces are blended in the European countryside in a way that is unknown in Pennsylvania, and the barns bear no large murals of stars (or anything else for that matter) to set them apart from other buildings in the landscape.

Figure 16: Stars in the Architectural Traditions of the Palatinate in Rhineland-Pfalz and Rhine-Hesse, Germany. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Clockwise from top left: A door panel carved with six-pointed rosettes, Keiserslautern; rosettes and a cross on the ventilators of the fifteenth-century St. Martin’s Catholic Church, Ober-Olm; 1891 house blessing inscription for Jos[eph] and Katherina (Theobald) Bootz, Oberalben; a rosette on the eave of a half-timbered home in Romersheim; an arched farmyard gate, featuring a sunrise, Oberalben; a whirling swastika on a home in Romersheim; a house blessing inscription for Karl and Katherina (Gilcher) Helm, 1883, Oberalben.

Figure 17: An elaborate rosette on the back of a nineteenth-century chip-carved chair from the Palatinate, from the collection of the Mennonite Research Center, Mennonitische Forschungsstelle Weierhof, Germany.

Nevertheless, the same basic star patterns emerge as a common theme in the Rhineland countryside with a close inspection of the timber framing of homes, painted and carved furniture, the stonework of churches, cemeteries and tombs, and the widespread use of architectural inscriptions. Although smaller and more subtle than the large barn stars of Pennsylvania, these carved, painted, or inscribed stars are often found in significant locations, above doors and windows in centuries-old town houses, carved into arches and fenestration of city gates and churches, inscribed into the eaves or upper gables of timber-frame buildings, or integrated into elaborate house blessings.

But just as elements of the architecture of the Pennsylvania barn can be traced to parts of Switzerland, so too are Swiss alpine farmsteads, called folkhouses,23 some of the most decorated structures in Europe, combining a wide variety of house inscriptions, geometric motifs, religious emblems, and heraldry, or family crests. This combination of decorative and religious elements produces a decidedly different aesthetic than the barns of Pennsylvania, but the basic star patterns are still present, suggesting the likelihood of a common origin.24

The appearance of celestial elements on architectural inscriptions is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the European connection to Pennsylvania’s barn stars. Often featuring stars, dates, the names of the founding family or builder, and mottos or religious poetry, European house and barn inscriptions are the intersection point of the religious and the mundane, and the integration of belief into the domestic and agricultural spheres.

Located above the front door or façade of the house, at the transition between the inner and the outer worlds, separating the public and private, these inscriptions serve as public dedications of establishment and blessings of the house and occupants. While these blessing inscriptions are diverse in format and structure, common themes are present throughout the tradition, indicating a number of parallel approaches to the dedication of a building. Some of these European blessings are no more than date-stones, capturing the specifics of the time of construction, while others are literary and religious, alternately invoking divine protection or offering some inspirational message for those passing by.

Two excellent examples of these blessing inscriptions, written in tandem with circular star patterns remarkably similar in form and scale to the barn stars of Pennsylvania, adorn the façade of a sixteenth-century Swiss folkhouse in Aeschi, Canton Solothurn. Folkhouses are massive alpine farm dwellings combining the house, barn, stables, and grain storage under one roof for convenience during the harsh winter weather. The Blümlisalp Chalet folkhouse, built in 1571, bears the following prayerful inscription:

Herr Höchster über uns mit deiner Gnaden Hand beschutz uns Haus und Dorf vor Krankheit, Sturm und Brand, Amen. (Highest Lord above us, with your graceful hand protect our house and village from sickness, storm, and fire, Amen.)25

Elsewhere on the same structure, an inspirational inscription is also proudly displayed in letters large enough to be read from a short distance:

Nicht im Feld und auf den Bäumen, in den Herzen muss es keimen, wann es besser werden soll. (It is not in the field nor in the trees, but it must germinate in the heart, if one is to become better.)

These two inscriptions characterize two primary genres of architectural blessing inscriptions in Europe, namely, those which serve to invoke the protection of the divine, and those which serve to inspire righteous living.

Echoing the house-name of the Blümlisalp folkhouse in Aeschi, named after a so-called “floral” peak in the Bernese Alps, its latter message, that all true betterment must proceed from the heart, makes use of a botanical metaphor, comparing the refinement of the human soul to the blossoming of a flower. This clever connection may also shed light on two large geometric designs situated directly below the gable of the roof, which appear to blend both floral and celestial geometry, just as the two inscriptions alternately appeal to righteous living on earth and the protection of the heavens.

While these two classic examples of European house blessing inscriptions are positively rife with symbolism of the sacred, not all European blessings offer such detailed explanations to accompany the geometric visual depictions of floral and celestial patterns found with them. Just like Pennsylvania’s barn stars, some of the alpine Swiss decorated folkhouses feature large star or floral patterns with no accompanying text to lend meaning to the art. Nevertheless, such stars are often placed in locations that suggest a silent blessing to the structure, such as under the roof overhang or at the upper gable apex, simulating the starry heavens above.

Similar uses of stars are found in the alpine architecture of Switzerland and Austria, and along the border with northern Italy, as well as in Alsace, France, bordering the Rhine to the west, and across the Rhine in the Black Forest of Germany. While no one region of Europe can claim to be the single point of origin of the Pennsylvania Dutch culture, such is also the case for the Pennsylvania barn star. Just as the Pennsylvania Dutch proceed from a wide variety of European roots to form a distinctly American culture, currents of artistic expressions from many regions poured into Pennsylvania to create new artistic traditions in America.

Figure 18: Above (clockwise from the top left): A spread of circular house and barn blessing plaques—An 1820 barn star from Perry Township, Berks County; an elaborate star from the 1801 Isaac Bieber Homestead, near Kutztown, Maxatawny Township, Berks County; an 1805 star on a Georgian farmhouse, Oley Valley, Berks County; a six-pointed star in plaster on a mill in Northern Lehigh County; a sixteen-pointed star painted on a plaster farmhouse medallion, ca. 1780, Upper Frederick Township, Montgomery County; 1816 Peter Solomon Steckel House, Egypt, North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County; 1819 barn star on the Kistler barn, Greenwich Township, Berks County; an eight-pointed star in plaster on a farmhouse in Upper Macungie, Lehigh County; 1813 Joseph Peter barn, Washington Township, Lehigh County. Bottom: Paired house blessings painted on wooden plaques on the 1819 farmhouse of Johannes and Anna Maria Bolman, and their son Jorg Bolman, Millcreek Township, Lebanon County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Architectural Blessings and the Earliest Barn Stars

Among the earliest expressions of Pennsylvania’s folk art stars still extant in today’s landscape are those which appear in the domestic and sacred architecture of the first communities established by the Pennsylvania Dutch in the southeastern part of the state.

Figure 19: An elaborate house blessing plaque dated 1820, with painted faux-brick border from North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County. Courtesy of Eric Claypoole.

In a similar manner to European blessing inscriptions, early examples of painted architectural medallions emblazoned with stars appear on early architecture along corridors of early settlement, stretching from Northern Montgomery County clear to the Blue Mountain ridge bordering Berks County to the north. Featuring colorful geometric patterns in combination with early dates, initials, or even full names, these early structures run the gamut of architectural expression—everything from houses built in the late eighteenth century, to early nineteenth- century houses, barns, and mills.26

With elaborate examples located in Berks, Lehigh, Montgomery, and Northampton counties, some of the most notable of these star medallions occur on English Georgian farmhouses on the upper gable apex. One of the earliest of these Georgian houses, located in Upper Frederick Township, Montgomery County, features two sixteen-pointed stars with split points in contrasting green and white painted on plastered medallions on either of the upper gables. While no dates or names can be found on this particular dwelling, which dates to the 1780s, a central circle in the middle of the star is large enough to have featured a date. This is comparable to another star found on a nearby barn in Douglass Township, which bears the remnants of a six-pointed rosette with a central circle of the same size, inside of which is a date from the 1780s that is weathered beyond full legibility. This latter example occurs on an original wooden date-board set into the masonry of the gable end of an English bank barn, which was modified with the addition of a forebay to match the local Pennsylvania barns favored by the Pennsylvania Dutch.

In both of these early Montgomery County examples, it is clear that Pennsylvania Dutch people created a hybrid of English architectural styles and Germanic features, reinforcing the notion that the culture was formed from a culmination of Pennsylvania’s diverse communities. These early forerunners to the barn stars must be considered in this light—not as a transplant of European artistry, but as something formed of new American identities.

Dozens of these medallion plaques exist, with scattered examples in remnants along the Kings Highway in Lehigh County, in the Oley Valley of Berks County, and along the base of the Blue Mountain, stretching throughout Northampton, and Northern Lehigh and Berks counties.

Figure 20: This semi-circular house blessing board was salvaged from the upper gable end of a stone farmhouse built for John and Lydia Anders in 1849, and originally located near Towamencin, in Lower Salford Township, Montgomery County. Courtesy of the Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center. Glencairn Museum staff photo.

A wide variety of such inscriptions in alternate formats can be found on the gables of early nineteenth-century barns and houses throughout Pennsylvania. These include semi-circular date boards featuring images of the rising sun in Northern Lehigh, arched and rectangular plaques presenting stars and floral motifs along the border of Berks and Lebanon Counties, as well as semi-circular or oval-shaped plaques displaying images of stars or the Federal Eagle in the corridor of the Perkiomen Valley spanning Berks, Lehigh, Montgomery, and Bucks counties.

Some of these plaques and their dated inscriptions highlight the sense of pride of ownership present in the decades immediately following the Revolution, and the emergence of a new American identity in the era of the Early Republic. One such pair of house blessing inscriptions records the names of revolutionary soldier Johannes Bolman and his wife Anna Maria Bolman, who settled near Millbach on the border of Lancaster and Lebanon counties following the receipt of Johannes’s compensation after the war. This property was established for the purpose of sustaining each subsequent generation, and Johannes and Anna Maria’s son Jorg’s name appeared on a plaque adjacent to the one recording his parents’ names. On each of these plaques, flowers and rosette stars connected by vines burst forth from an urn, a symbol of growth, emergence, and renewal, paralleling the intentions of the house blessing plaques.

The most celebrated of all of these architectural medallions is the 1819 barn blessing attributed to the Kistler family of Greenwich Township, Berks County.27 This painted wooden medallion is in all respects a highly developed forerunner to the distinctive star patterns in Northern Berks. Like its peers throughout Lehigh, Northampton, and Montgomery, it was painted on a medallion composed of two wide boards and set into a circular recess in the original masonry. There it was anchored with hand-wrought nails to hidden “sleeper” boards in the recess behind the medallion. A six-pointed star with a central pinwheel painted in the alternating colors of yellow and green, framed within a border of three concentric circles, bears a striking resemblance to the classic barn stars painted with eight, twelve, and six points throughout the region. An inscription fills the spaces between each star point with initials and a date, reading “S K 1819 M K”—honoring the husband and wife who established the farm property. Although it is possible that the initials were for Samuel J. and Maria Elizabeth (Ladich) Kistler, buried at the nearby Jerusalem Union Cemetery in Stony Run, records from this time are scant and cannot be confirmed.28 Nevertheless, this inscription outlines the function of the earliest barn stars in the region as a colorful means to commemorate the establishment of a property.

The evidence of dozens of these earliest barn stars suggests that they were mostly produced within the half-century following the American Revolution and no examples are known to exist after 1840. Perhaps this is because these early architectural blessings were entirely dependent upon the stone construction of the upper gable as a place to anchor the decorative plaques, and when architectural forms changed, the format and style of the architectural blessing was adapted into the barn stars we recognize today.

Figure 21: A six-pointed rosette on the carved keystone above the door of the 1767 New Hanover Lutheran Church, serving the oldest continuous German Lutheran congregation in America, located in New Hanover Township, Montgomery County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Sacred Architecture

Even earlier than the oldest examples of house and barn blessings, images of stars and flowers emerge from the landscape as central symbols of sacred architecture. Especially among Protestant congregations, celestial images served as focal points of early churches constructed as meetinghouses in the Georgian and Federal styles, where crosses were not used to identify their Christian faith. For these early American congregations, many of whom sought to distance themselves from the cathedrals of the Roman Catholic establishment in Old Europe, the cross was thought to represent one’s internal faith journey, but was intentionally avoided as an emblem of the faith.29 Instead, a number of early Pennsylvania churches featured six-pointed rosette stars on the structures in strikingly prominent locations.

Among these early churches are the 1767 New Hanover Lutheran Church in Montgomery County, constructed for the earliest German Lutheran congregation in the United States, organized in 1700.30 The building features a six-pointed rosette on a carved keystone above the main entrance, along with an inscription honoring the names of the builders. In a similar manner, the 1806 Swamp Union Church of Reinholds, Lancaster County, features a series of stones along the upper eave of the façade, listing the names of the church builders, masons, and carpenters, along with a series of rosettes.31

Within this particular context the rosette and the keystone suggest a thoughtful, intentional, religious significance, although no records exist to verify the original builders’ reasoning. According to Christian tradition, the keystone itself represents Christ, as the Book of Isaiah pronounces: “Behold, I place a stone in Zion.”32 Psalm 118 describes “the stone the builders rejected is become the chief corner stone,” interpreted by Christians as prophecy of the coming of Christ as the foundation of the church.33

The rosette takes this significance a step further, evoking the star that signified the birth of Christ in Bethlehem to the Magi,34 and again in the Book of Revelation: “I, Jesus, have sent my angel to give you this testimony for the churches: I am the Root and the Offspring of David, and the bright Morning Star.”35

Alternately, the form of the rosette has also been compared to the image of the lily,36 which graced the pillars of the Temple of King Solomon, and elsewhere refers to the renewal of the world by the coming of the Messiah: “I will be as the dew unto Israel: he shall grow as the lily, and cast forth his roots as Lebanon.”37 The builders of the New Hanover Lutheran Church were likely familiar with these popular biblical passages.

Figure 22: The elaborately carved dedication stone featuring a central rosette and an inscription of the 1787 Joseph Henderson Meeting House, serving the Great Conewago Presbyterian congregation in Adams County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

In a similar manner in Central Pennsylvania the Great Conewago Presbyterian Congregation established Henderson’s Meetinghouse for Scotch-Irish families and some Pennsylvania Dutch who settled in Adams County, and the structure included a large slate medallion featuring a six-pointed rosette along with the date of 1787 and the name of Joseph Henderson, the founder. The prominence of the rosette in the dedication stone suggests that the Calvinists may have ascribed similar meaning to the rosette.

Stars were also prominent in the churches of Europe, where many chapels and country churches were painted with star-ceilings depicting the canopy of the heavens complete with planets and constellations, as well as the sun and moon. These star-ceilings suggested to those worshipping within that the sanctuary mirrored the divine organization of the cosmos, as the creation and dwelling place of God. Star-ceilings were also documented in Pennsylvania churches, such as the Bern Reformed Church of Bern Township, Berks County; however, none of the original ceilings survive to this day.

Later Federal style churches of the early nineteenth century continued the tradition of integrating star patterns into sacred architecture. The 1815 Belleman’s Union Church in Mohrsville, Berks County, once featured six-pointed rosettes in the configuration of clear glass windows on the upper gable ends of the meetinghouse.38 Similarly, sunbursts once accented the gable windows of the 1805 Bindnagel’s Lutheran Church of Palmyra, in Lebanon County. These elements were the standards of Protestant houses of worship up until the Victorian era, when the Gothic Revival reaffirmed the cathedral as a desirable architectural form and the cross once again returned to church architecture, and gradually to rural Pennsylvania communities.

One might easily observe that some of these expressions are in keeping with marks and ornamentation favored by the building trades, and that stone masons and woodworkers frequently embellished focal points of buildings or used geometric designs in their maker’s marks. However, one need only look to the churchyards and cemeteries to see that such imagery extended beyond the realm of the trades and featured prominently in the symbolism of early gravestones, which were equally an expression of sacred, consecrated space.

Gravestones

These early gravestones commonly record the biographical descriptions of the lives of the faithful departed, including the dates of birth and death, the age at the time of death, as well as the names of spouses or parents, the number of children, or even an occupation or locations of birth and death. These life stories, provided in more or less detail, are framed with varying degrees of ornamentation and religious symbolism.

Again, the earliest Protestant gravestones deliberately avoided the use of the cross,39 and instead a diverse range of images appeared to serve as reflections of mortality and rebirth. Angels and winged busts suggested the messengers of heaven and the passage of the spirit of the deceased to the afterlife. Hearts depicted the seat of the human soul and its capacity to experience both mortal and divine love, while the skull, crossed bones, the hourglass, and the sickle represented the death of the body, and the harvesting of the soul.40

Many of these symbolic images were pictorial reminders of scriptural passages commonly read at the graveside, such as the image of the crown featured in the comforting words of Christ from the Revelation of John, “Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life,”41 or the gates of heaven.42 For the vast majority of gravestone symbols, biblical verses both inspired and reinforced the use of particular images, establishing a standard of meaning with the potential to be easily identified and widely recognized.

Many early stones feature images of flowers, especially three blossoms rising out of a funerary urn. This particular motif is commonly accepted as a symbol of resurrection, and repetitions of three invoke the Trinity. But floral patterns as a whole have a wide range of possible interpretations, including the frailty of mortal life as described in the Psalms, “As for man, his days are like grass; he flourishes like a flower of the field;”43 or represent Christ, the Messiah as described by the Prophet Hosea, “he shall blossom like the lily,” or as the Bridegroom in the Song of Solomon: “I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys.”44

These carved images of flowers also suggest the earthly realm of mortals, where in some gravestones the flowers are depicted at ground level, with a shining star above. One such gravestone, in the cemetery of Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church in Manheim, Lancaster County, was carved for Rosina McGartney, infant daughter of John and Elizabeth McGartney, who was born and died on the same day: May 27, 1784.45 This tragedy inspired the carved image on the stone, depicting the soul of the departed little girl under the illumination of a single star from above and surrounded by flowers below, suggesting her soul’s passage from the earthly realm to the celestial realm of the heavens.

Figure 23: Early Gravestone of Rosina McGartney, Courtesy of Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church, Manheim, Lancaster County.

This intricately carved headstone reads: “Departed this life, Rosina McGartney, the daughter of John McGartney & Elizabeth his wife, born and departed May 27, 1784.” This tragic inscription is now only partially legible, having been worn away by the elements over time.

The stone of Rosina McGartney was carved by a prolific anonymous stonecarver of Northern Lancaster, County, who created scores of gravestones throughout the Cocalico and Brubaker Valleys. His specialty was the image of the winged Sophia, a symbolic representation of the spirit of wisdom favored by some Pietist groups in Pennsylvania, especially the community at the Ephrata Cloister. The carver’s Sophia is often crowned with a star, a blossom, or a flame.46

However, in some cases images of winged human busts represent the soul’s transformation, as in certain stones in the Cocalico Valley of Lancaster,47 which depict a bust of the deceased on the west side of the stone, and the same bust, complete with wings, on the east side. These directions align with the most common orientation for gravestones: facing east, in the direction of Jerusalem and the rising of the sun, echoing the symbolism of Christ’s death and resurrection.

Carvings of rising suns are also common, as well as images of the waning moon, a symbol of the mortal soul committed to the earth.48 Stars and rosettes are among the most common gravestone images, depicting the beacons of the heavens, and symbols of divine order.

Rarely do such illustrated stones offer an inscription to elaborate upon the beliefs which undergird the images. One such stone, at Emanuel Lutheran Church in Brickerville, depicts a personified image of the sun and moon and two rosettes carved in relief, along with a series of incised stars, and the English-language inscription of lyrics by the Congregational hymnodist Isaac Watts:

God my redeemer lives,

Who often from the skies,

Looks down, and

Members all my dust,

till he shall bid me rise.49

This inscription confirms that such celestial images are neither whimsical nor merely polite decorations, but meaningful iconography describing the infinite heavens as the dwelling place of the divine and part of a sacred, ordered cosmos.

Figure 24: Bookplate and Birth Record for Marya Wenger, FFLP B-125, Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.

This highly embellished bookplate commemorates the birth of Marya Wenger on “the 6th of February, in the year 1845.” A nine-pointed star, hand-painted in alternating shades of red, yellow, and blue, is enwrapped in a floral vine. This illuminated inscription was pasted onto the inside cover of Marya Wenger’s New Testament, printed by Scheffer & Beck of Harrisburg in 1848. Testaments and prayer books are among the most personalized religious items, strengthening their role as tools of daily devotions.

From the Cradle to the Grave

This symbolism extends beyond the artistry of churchyard gravestones and equally embraces the highly embellished, formal documents celebrating birth and baptism at the very beginning of life. Featuring elaborate images of stars, angelic messengers, birds, and floral patterns, these illuminated certificates, or Geburts- und Taufscheine (Birth and Baptismal certificates), celebrate new life with depictions of the heavens and the natural world. Such documents are part of an art form recognized in the present day as Fraktur, named after the particular style of blackletter calligraphic writing called Frakturschrift.

The images accompanying these calligraphic documents have received much attention over the past century as manifestations of art poised at the intersection between symbolic, social, and religious narratives. Although Fraktur scriveners and artists did not always provide overt visual and textual relationships, certain examples provide powerful reminders of the way that such illustrations frame the sacred experience with images of the natural world and the heavens above—two essential components of a divinely created universe.

A particularly elaborate example that successfully integrates image and text into a coherent inspirational message is the certificate commemorating the 1771 birth and baptism of Johann Adam Laux, son of Peter and Cathrina Laux, produced on September 3, 1773 and attributed to Johannes Mayer of Bedminster Township, Bucks County.50 The central motif of the document depicts the face of a clock articulated with Roman numerals and a twelve-pointed rosette star, flanked on either side by verses from the Book of Psalms: “My time stands in thy hands,”51 and “Behold, my days are as a handbreadth to thee.”52 Below the clock stands an urn from which spring forth blossoms.

Figure 25: Birth and baptismal certificate for the 1771 birth of Johann Adam Laux, son of Peter and Cathrina Laux, created in 1773 by Johannes Mayer of Bedminster Township, Bucks County. Whereabouts unknown; from William J. Hinke’s History of the Tohickon Union Church, 1925.

Like early gravestones that carefully record the dates of one’s birth and death, and a reckoning of the age of the deceased person in years, months, and days, the Adam Laux birth and baptismal provides a reflection on the ephemeral duration of a human life, demonstrating the special emphasis of time in sacred material culture. Although the certificate provides only the year of birth, many such documents record not only the day, month, and year of birth, but also the sign of the zodiac, and occasionally the ruling planet or phase of the moon under which the child was born.53

A birth and baptismal certificate for Benjamin Meyer (1800-1824), son of Heinrich and Mary Meyer of Miles Township, Centre County, records his birth “in the year 1800, on the 26th of August around 4 o’clock in the morning, under the Sign of the Scorpion.”54 The celestial images of the six-pointed rosette stars are notable, considering the emphasis placed upon the birth of the child under the constellation of Scorpio. While this is a common feature of both printed and handwritten certificates, it is unusual that this detail is given more prominence in the limited space of the central circle of the document than even “the father and mother of this child;” they are listed as the baptismal sponsors, but their specific names are absent.

Figure 26: Birth and baptismal certificate for Benjamin Meyer, giving the precise hour and sign of the zodiac under which the child was born on August 26, 1800 at 4 o’clock in the morning, under the sign of the scorpion, in Miles Township, Centre County. Courtesy of the Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center. Glencairn Museum staff photo.

The care and detail displayed in these records of human life serves as a reminder, not only of the particulars of one’s birth, but also the brevity of life. In addition, this later consideration is meant to inspire the living to consider the spiritual condition of their lives, and examine their deeds and accomplishments. Printed birth and baptismal certificates from the mid-nineteenth century, produced by the thousands throughout Pennsylvania, reflected the shortness of life in these common lines of poetry:

Our wasting lives grow shorter still,

As months and days increase,

And every beating pulse we tell,

Leaves but the number less.

The year rolls round and steals away,

The breath that first it gave,

Whate’er we do, whate’er we be

We are traveling to the grave.

Infinite joy or endless woe

Attends on every breath,

And yet how unconcern’d we go,

Upon the brink of death!

Waken, O Lord! Our drowsy sense,

To walk this dangerous road;

And if our souls are hurried hence,

May they be found with God.55

While these reflections may at first appear to be a morbid intrusion into a document celebrating new birth, for centuries among the Pennsylvania Dutch, the anticipation of death began at the very beginning of life, when infant and childhood mortality was an all too common experience; death claimed equally the young and old, the rich and poor, without prejudice for one’s achievements or station in life.

An elaborate barn blessing near Sinking Spring, Berks County, that echoes these sacred sentiments was created in 1802 by the stone-mason Heinrich Iertz (Hertz). It reads: “God can build and destroy. He can give and he can take, to each as it pleases him.” The blessing inscription is enclosed in an arched cartouche, topped with a simple pattern composed of four whirling rain-drop shapes.56

This emblem was once one of the most popular images in Pennsylvania Dutch folk art, and featured prominently on the barns of Montgomery, Lehigh, and Bucks counties.57 An ancient symbol associated with good luck, the swastika comes from the Sanskrit word for “bringer of good fortune,” and was used widely across the world by many cultures throughout the millennia. This pattern was used widely in Pennsylvania, and throughout the United States, long before the European adaptation of the motif as a German military symbol for the Third Reich during the Second World War. Nevertheless, this particular curved, lobed pattern has persisted in many variations as a barn decoration, as its gentle appearance suggests the opening of a flower, the turning of a fly-wheel, and the sun’s passage of time throughout the ages.

This whirling wheel parallels the biblical reflections on mortality and the frailty of human endeavors, presenting an important aspect of the Pennsylvania Dutch folk-cultural worldview in which the interrelation of life and death, heaven and earth, the temporal and the eternal, are all in the hands of the divine creator.

Figure 27: Barn Blessing in Plaster, Photo by Guy F. Reinert, ca. 1950. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

This elaborate barn blessing features floral motifs and a whirling flywheel pattern, along with a German inscription: “1802. The Lord can build and he can destroy; he can give and he can take to each as it pleases him. Heinrich Hertz, Stone Mason.” Although the barn structure still stands today, the German inscription and symbolic elements are no longer visible.

Domestic and Celestial

While various forms of celestial symbolism are common, and perhaps even expected, in both religious art and sacred objects, the Pennsylvania Dutch applied the same motifs on even the most mundane of objects. Artists and craftspeople carved, embroidered, wove, painted, and inscribed the same celestial patterns on decorated chests, butter-molds, coverlets, spoon-racks, spice-boxes, cheese-presses, tape-looms, rifles, powder horns, musical instruments, trivets, and wood-working tools. While this form of common, everyday artistic expression could at first appear to suggest that such common motifs held little or no discernable meaning to the makers and owners of such everyday objects, instead such decorated objects communicate a remarkable sense of craftsmanship, and thoughtful appreciation of the mundane that is essential to the Pennsylvania Dutch culture. This certainly does not indicate that each and every object in the home was somehow elevated above the experience of daily life. Instead, it suggests the opposite, that the stars and their artistic representations were a part of everyday life, and that every aspect of life was equally deserving of their celestial presence—both sacred and mundane.

In each of these instances, the star motifs are not merely placeholders, but evidence of folk art and belief in process. While previous generations of scholars have pointed to the diverse application of celestial motifs throughout the culture as an indication that the designs were purely decorative, with no inherent meaning,58 on the contrary, the presence of the stars throughout even the most mundane contexts could suggest that the stars played an important role in folk art as a form of social ritual. Celestial motifs were present at an overwhelming majority of life’s transitions in early Pennsylvania, whether they are found on a decorated cradle at the beginning of life; on a hand-illuminated certificate for the baptism of a child; on a decorated blanket chest given to a young bride at her wedding; on an inscribed blessing stone of a new home; on the façade of a well-maintained barn; or on the headstones of the faithful departed. These celestial images followed early Pennsylvanians through life, offering many layers of meaning to common human experiences.

Interestingly, while many of these traditional motifs are commonly identified as “stars,” it is rarely considered that the geometric expression of a star is quite different from the visual form of an actual star, which appears as a point of light in the celestial sphere. This type of geometric pattern can therefore be called abstract, as opposed to realistic.

Figure 28: Haus-Segen (House Blessing) Isaac Palm, Brecknock Township, Lancaster County 1860.

This classic house blessing is a reflection on departure from the household, asking the divine in rhyming couplets for protection of the home during one’s absence. The blessing reads in translation: “In God’s name, I go out. O Lord, reign over the house today. Let the lady of the house and my children be commended unto thee, O God…” Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

While they are not strictly representational, these abstract designs became widely accepted as images of the stars over thousands of years of folk-cultural use across the globe. This universal identification of radial geometric motifs as having celestial qualities would seem to indicate that elements of the designs themselves were inspired by, and directly related to, the observation and experience of the stars. Visual qualities such as symmetry, rotation, balance, regularity, and cyclicality point to the celestial movement and progression of the stars as the source of this inspiration.

Indeed, even until fairly recently in human history, the stars in their courses were identified, along with the rising and setting of the sun and the phases of the moon, as the clearest indicators of the passage of time and the belief in a stable, ordered universe. It is therefore not surprising that the observation and monitoring of the progression of the sun, moon, and stars is a central feature in many traditional, agrarian societies, where celestial activity is believed to directly influence the mechanics of earthly life.

Figure 29: Chip-Carved Mattress Paddle, Nineteenth Century. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

An elaborately carved wooden paddle used for preparing and smoothing a rye-straw mattress tick on a nineteenth-century rope bed. Such highly embellished objects were typically carved during winter evenings and presented as gifts for sweethearts or loved ones. Some of these objects were dated and initialed to demonstrate a sense of pride in craftsmanship, while others, like the paddle, are anonymous and without attribution.

Butter molds were once common everyday objects used by rural households where butter was made by hand. After the butter was churned, it was stored in one-pound blocks that were portioned using butter molds, which often bore carved geometric, botanical, or animal motifs that would leave a distinctive mark on the butter. This was not only a fancy presentation of the butter for household use, but also for sale, as a profitable dairy product, and decorations enhanced its salability. Left: A butter mold with a whirling swastika pattern. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer. Right: Eight-pointed star butter mold. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. Glencairn Museum staff photo.

Astronomy and the Almanac

As with many agricultural societies, the Pennsylvania Dutch possess a well-developed system of beliefs concerning the movements of the heavens and their effects on earthly processes, as well as on botanical, animal, and human affairs. While the bulk of these beliefs in Pennsylvania proceed from the European traditions of the agricultural almanac, these conceptions have been liberally blended with religious attitudes. Thus, the stars in their courses, along with the rising and setting of the sun and the phases of the moon, were not only regarded as the clearest indicators of the passage of time, but were emblematic of the belief in a stable, ordered, sacred universe.59

The progression of the sun, moon, and stars are a central feature in the agricultural almanacs still used in the present day, where celestial activities are charted and interpreted for their influence on the mechanics of earthly life. Each almanac is essentially an annual household reference booklet, and includes the liturgical church calendar of saints’ days and festivals, charts of the lunar phases, the day-to-day progression of the zodiac constellations and planets, as well as calculations for the appearance of comets, eclipses, and other astronomical phenomena. This information was once used to orchestrate the activities of daily life into a meaningful and coherent whole, and the almanac is still used by some farmers and gardeners today.60

Whether in planting or harvesting, felling trees or tilling the soil, baking bread or fermenting vinegar, breeding or slaughtering livestock, bearing children or getting married, there were believed to be appropriate days of the week, times of the month, phases of the moon, saints’ days, or alignments of celestial bodies which would either positively or negatively affect the outcome of life events.61 This system was an attempt to harmonize the progression of human life with the progression of the heavens, and was believed to be the manifestation and visible order of the divine will.

Figure 30: Woven coverlet decorated with stars and floral motifs, ca. 1830. Hamburg, Berks County. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

A late nineteenth-century tin dust pan, featuring a six-pointed rosette pattern with split, lobed star points and small cross motifs between each point, just like some local barn stars. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

A nineteenth-century wooden canteen inscribed with six-pointed rosettes carved from a single block of wood, with pairs of stars on either end. Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

Almanac traditions were followed to different degrees by different families in a way that was by no means uniform. However, the system of beliefs was so firmly established that the agricultural almanac was one of the most common works of printed literature found in the Pennsylvania Dutch home, second only to the German family Bible.62 While to modern audiences, these two books may appear to represent opposing systems of thought and belief, on the contrary, it was biblical literature itself that undergirded the belief in the efficacy of the almanac tradition.

According to the Book of Genesis, it was on the fourth day of creation that the creator said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them serve as signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years, and let them be lights in the expanse of the sky to give light on the Earth.”63 This message is continued in the Book of Ecclesiastes, which explains, “To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted; A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up. . .”64 The Old Testament is not the only place in which the celestial sphere is celebrated as a means of understanding the will of the divine. In the New Testament, the birth of Jesus Christ is signaled by a star in the east,65 and in the Book of Luke, the second coming of the Messiah is said to be heralded by astronomical phenomena: “There will be signs in sun and moon and stars, and on the Earth dismay among nations . . . for the powers of the heavens will be shaken.”66 In all of these biblical passages, the stars in the sky are viewed as a constant, ever-present reminder of divine order, only changeable under the most momentous of circumstances.

Figure 31: “The heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament sheweth his handywork.”—an engraving by Carl Friederick Egelman (1782-1860) of Mount Penn, Berks County, and the frontispiece of The Complete Explanation of the Calendar, with a Comprehensive Instruction of the Heavenly Bodies, by the Rev. E. L. Walz, Lutheran minister of Hamburg, Berks County, printed in Reading by Johann Ritter in 1830. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

It is through this concept of agricultural and religious order that the significance of the stars in Pennsylvania Dutch culture can begin to be understood, not merely as points of light in a distant sky, but as powerful forces which were believed to govern even the most minute aspects of life. At the same time that celestial folk art illustrations connect a people with their sense of placement in the cosmos, in a similar manner, traditional folk art connects a culture with its ancestral legacy. The repeated use of folk art motifs over many generations creates a sense of continuity in the aesthetic experience of the domestic and sacred spheres of life. This sense of chronology not only applies to the intergenerational use of such traditional motifs, but also reflects the cradle-to-grave application of folk art over the span of a human life in domestic and sacred material culture. The reference to time, therefore, is an important element in the interpretation of celestial symbolism.

The order and progression of the heavens is essential to the human understanding and experience of the passage of time. According to the Lutheran Minister E. L. Walz of Hamburg, Berks County, in his 1830 astronomical treatise entitled, Complete Explanation of the Calendar, with a Comprehensive Instruction of the Heavenly Bodies, the celestial division of time “brings light and order in all the multitudinous and the innumerable relationships and operations, with which the people of Earth are interconnected.”67 This belief was well established among the Pennsylvania Dutch, as it relates to external physical affairs, as well as communal and personal spiritual life.

The frontis engraving opposite Rev. Walz’s title page depicts the celestial sphere, complete with the moon, stars, and the milky-way, surrounded by the signs of the zodiac, and the sun shining forth as a beacon from a stylized church steeple. The opening verse of the nineteenth Psalm of David accompanies the image: “The Heavens declare the Glory of God and the Firmament sheweth his handywork.”68

This engraving is the work of Carl Friedrich Egelman (1782-1860) of Reading, Berks County, the foremost astronomical calculator of Pennsylvania, whose tables and engravings of the movements of the heavenly bodies were featured in annual farmer’s almanacs throughout the state of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as his own Egelman’s Improved Almanac published in Reading, where he lived on Mount Penn.69 A master engraver, Egelman’s work combined astronomical and religious imagery, and the cover of his almanac featured an engraving showing a cosmological diagram, including the phases of the moon, the sun and planets, the signs of the zodiac, the months and seasons, as well as the German text from Psalm 19, used as the motto of the calendar. Egelman depicted himself in the very center with the horn of a messenger, proclaiming his astronomical observations for the glory of his divine creator.70

Figure 32: Cover engraving of Egelman’s Improved Almanac, by Carl Friederick Egelman (1782-1860) of Mount Penn, Berks County, the foremost astronomical calculator of Pennsylvania, whose tables and engravings of the movements of the heavenly bodies were featured in annual farmer’s almanacs throughout the state. It depicts the phases of the moon, the planets, the signs of the zodiac, the seasons, as well as Psalm 19 in German: “The heavens declare the glory of God; And the firmament showeth his handywork.” Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Archive, Myrin Library, Ursinus College.

The prolific Egelman also produced printed birth and baptismal certificates, an extensive series of engravings for a manual for penmanship instruction,71 and penned poetry that was both religious and astronomical. In his German-language poem, Empfindungen eines Astronomen (Sentiments of an Astronomer), which appeared in Der Neue Readinger Calender (The New Reading Almanac) of 1822, Egelman ponders the wonders of the cosmos:

Figure 33: A heavily used Egelman’s Improved Almanac for the Year of Our Lord 1846, with the original leather loop still intact, commonly used for hanging the almanac on a nail by the kitchen door for ease of daily reference. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer, Gift of Reginald Good.

With what almighty, infinite Force

Were the planets and stars,

Celestial works of eternal space,

Brought out of the dark night into orbit?

Who maintains the order of the radiant stars?

Who guides the suns at wondrous distance?

Who restrains the orbit of the laughing moon?

If thou, almighty Creator, did not there abide?

Who contains the turbulent seas?

Who confines the hordes of preying beasts to the wilderness?

Who provides nourishment, who gives bread for all?

Who defends from the dangers of abject poverty?

Who endows humanity with the capacity to think?

From whom proceeds reason, and who can guide it?

And who maintains the scales of all things in balance?

Thou dost, O Creator, and thine is the kingdom.72

It is notable that Egelman’s period of influence as an astronomer, almanac maker, and artist—roughly 1820-1860—coincides with precisely the time and place when celestial images were widespread in the traditional arts, when geometric representations of the stars became a popular art form in Berks County. While likely mere coincidence, this suggests perhaps that religious and folk-cultural interest in the movements of the heavens, and the traditional farmer’s almanac, were at a high point among the rural Pennsylvania Dutch at that time.

The Establishment of a Tradition

Around 1840, a general shift in construction methods occurred throughout the region, when the abundance of cheaply-produced wooden siding enabled the widespread construction of barns with framed gables rather than stone. In the absence of a stone gable, star patterns and date inscriptions were painted directly onto the siding of the barn, although the new location of preference was on the front forebay wall, where details like names or dates were closer to the viewer and far easier to read. Matching the dimensions of this new location, the arrangement required two, three, or more stars to adequately divide the expanse of the forebay siding into manageable visual spaces. The date of the structure was often recorded below the star in the very center of the barn, where there was sufficient area for the inscription of the name of the family, and sometimes the name of the farm itself. The earliest documented structures with this arrangement dates from the 1840s and 1850s.73

Numerous barns of the mid-nineteenth century in Berks and Lehigh are adorned with three or more stars across the front of the barn, in concert with other painted elements that accent the architectural form of the structure. These include decorative borders on the bottom edge of the siding, or in vertical stripes along the edges and dividing the front siding into equal areas, as is common along the border of Western Berks and Lebanon. Most common of all are the painted outlines around doors and windows, in most cases crowned with a semi-circular arc or half of a barn star, illustrating the rising sun below the dome of the heavens. On the bank side of the barn, small stars or even hearts are clustered above the large wagon doors, and vertical stripes outline the dimensions of the entrances.

Figure 34: After 1840, when many barns were built with no stone gable to anchor a circular medallion to mark the date, artists painted these dated barn stars on the front and center of the forebay siding. Upper Milford, Lehigh County. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.