Glencairn Museum News | Number 6, 2020

The obverse and reverse of Glencairn Museum’s halfpenny token depicting the New Jerusalem Temple in Birmingham, England, issued by Peter Kempson in 1796. For a high-definition, “zoomable” photo of Glencairn’s token, go to the Google Arts & Culture entry here.

Figure 1: Video of the 3D computer-rendered reproduction of the New Jerusalem Temple.

Joel, this is a very niche project. How did you get started on this?

It all started with wanting to learn the Blender program (Figure 17). I was intrigued by doing 3D modeling. I happened to be scrolling the Glencairn Museum Facebook page and found the Kempson token (Figure 2). I saw it and thought it was neat, because it doesn’t exist anymore. I decided to bring it back (Figure 1). There was material to work with, and I thought it was a worthwhile project. So, I jumped to it and worked from there.

Figure 2: Obverse of the halfpenny token depicting the New Jerusalem Temple in Birmingham, England. See a high resolution, “zoomable” entry for this object on Google Arts & Culture here.

Why did you want to learn Blender in the first place?

I really wanted to make some isometric pixel art—old-school, video game-looking stuff. I was getting frustrated trying to translate 3D into 2D, and then I asked myself, “Why am I putting in all this effort when I can have a program do it for me?” But I got so distracted with the New Jerusalem Temple that I have yet to attempt what I initially set out to do.

You started out doing pixel art in middle school, correct?

I did. It’s a similar mindset, really. When I was a kid, I started on Microsoft Paint, and I would work in pixels (Figure 3). That would expand into characters, and it ultimately became a mindfulness exercise—but I didn’t think of it that way as a kid. I see the same experience in Blender now. For example, I would set out to do a “finishing touch” on part of the Temple, and then it would be well past my bedtime and I would still be going strong because I’d get into it and focus.

Figure 3: Some examples of Joel Glenn’s early pixel art.

I’m glad you mentioned “mindfulness.” When you were working on the Temple, did you get any insights into what it might have been like to worship in that building when it was new?

I hoped I would, but I got caught up in technicalities, and it wasn’t until afterwards that I would wonder. For example—and you don’t see it because it’s not in the video—they had an organ in there, in the gallery. And I wondered—because it’s not a big building—but according to descriptions the building could hold at least 600 people. It’s a formal space, but it would be a very intimate space—at full capacity you’d be on top of each other! I can imagine that in such a small space belting out worship hymns would have been quite impressive.

Figure 4: Putting the “finishing touches” on a pew in the Blender model.

The rector at the New Jerusalem Temple was the Rev. Joseph Proud (1745-1826; Figure 6). He is known for producing the first hymnal written expressly for New Church worship (Figure 5). Is that his music that we hear in the background of your video?

I could only find a few of the tunes that Proud used in his hymns. His hymnal tells you the meter of his hymns, but it doesn’t tell you the tune that goes with it. I did find a couple of his tunes, but I couldn’t find high-quality versions. So, I didn’t use any of them in the final version of the video. He certainly was prolific in turning out hymns. I’m not a great judge of lyrics and poetry, but his message seems pretty consistent: he hammers home the New Jerusalem and the Second Coming. That seems to be his thing.

Figure 5: Hymn book and description, from The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916).

For you as a priest, when you read his lyrics do you notice any continuity of thought? Would his work feel comfortable to engage in and to sing today if you were in a worship service?

I think that the singing felt very familiar. It was also interesting. Proud had a little preface [in his hymn book] where he is very adamant about the details of the New Church. He writes a very lengthy description of what the New Church stands for. And I’m very familiar with the way he writes. It sounds like any early New Church writing that I’m familiar with—up to the early 1900s, even. Proud is putting the core ideas out there in somewhat intellectual but very strident terms.

Figure 6: Rev. Joseph Proud, from The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916). Colorized by Christopher Barber, 2013.

Here we have the first New Church temple and the first New Church liturgy in the same space. These folks were really making their mark with this location. Did all that “newness” make it difficult for you to examine other churches of the time for reference?

For certain elements I did [refer to other churches]. It was more for detail that I was looking. “How do I illuminate?” “What would pews look like?” “What would a pulpit look like?” “What materials would be used?” I found myself doing a lot of searches for Georgian era details. There’s such a clear description of the actual structure of the building that I didn’t even need to look further afield. So, I’m not sure how it compares to other churches at the time. It does seem like the curved pews, and then the matched curved back wall, are distinctive elements.

It’s clear that they wanted to be distinct. They wrote a new liturgy for a new church. Did they also build a new kind of building?

That’s definitely the idea behind it. The idea is, “we’re mostly doing the style of what contemporary Christianity does, but we’re adding in some changes with the hope that we’ll develop it further away from that basic model.” Though some today might say that we haven’t moved that much further along from there. But, again, in his liturgy Proud definitely mentions that we need a new style of ritual.1

They definitely had in mind correspondences,2 and descriptions of churches in heaven [from Emanuel Swedenborg’s writings] when they were designing the Temple itself. So, the hope was to design the Temple based on New Church ideas. Perhaps other churches didn’t follow that same model, but they were trying to make a start here, to be distinctive.

This building was a New Church place of worship for only a few years. Afterwards there were some significant changes made by later groups. What was it like for you, working back through those changes to get to the original Temple?

That was quite interesting and hectic, because at first I just took images, descriptions, and diagrams at face value. But then I had to start teasing to determine who said what first, and what might have changed in the interim. For example, looking at the diagram (Figure 7), it looks like there’s a big schoolroom on the front, and a big assembly hall. But if you look closely, you realize that’s actually all later additions.

Figure 7: Schematic of the New Jerusalem Temple as it appeared at the time of Schreck’s investigation, from The New Church in Birmingham (1916).

Another example: In Osborne’s watercolor (Figure 8), if you look closely you can see the vestry and library area projecting off the back of the church. In the painting it has two stories, but Eugene Schreck (Figure 9), in his book on it, said they later looked more closely at the brick [above the vestry] and could see that the style of brick changed at the second story. His assumption was that was because [the second floor] was a later addition.3 So that watercolor, which is trying to be authentic [to 1791], has that error in it.

“That error” being the second floor above the vestry?

That’s correct. There was no second floor originally, but Osborne imagined that there was.

Figure 8: Recreation of the New Jerusalem Temple at its dedication, produced in watercolor and preserved in The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916).

Osborne was able to visit the actual building while it still stood (Figure 10), and still he made errors in his rendering of the original. Do you have any uncertainties about your own rendering?

Figure 9: Rev. Eugene Schreck as a young man. Photo: Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

Well, something that I puzzled and puzzled over, and could not for the life of me figure out, was how they got up to the gallery. Multiple accounts mention [the gallery], so it seems pretty clear that it’s there. But how it fits into the greater whole is a mystery to me. No one gives a clear indication of the stairs. I had to make something up, essentially.

Were the accounts you used contemporary observations from when the Temple was still standing? Or were they recollections and suppositions?

A lot of them were after the fact. We have the Kempson coin, which is a simple but clear image of what the front of the Temple would have looked like. And then it’s nice having Schreck’s book, which was written in 1916, about the history of the Temple. He did a lot of on-the-ground research, because he wrote while it was still standing so he could actually stop by and look around.

It’s frustrating to think how many little details are lost. Schreck could just trot on down to the Temple, look around, glance, and investigate. It’s like what I said about the rear addition; someone had to be there to understand what things really were.

Figure 10: Rear view of the building in its final form, from The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916).

What’s one resource you wish you could access?

If I could have anything, it would have to be a photograph from the pulpit looking towards the front of the building. That would have been immeasurably helpful.

If you could have another thing what would it be?

I’d like to see what the pulpit actually looked like originally. There is that platform up at the front, which I believe is original. It’s described as an altar with a mahogany railing, and I think what we see in the photograph is what’s being described there (Figure 11).

Figure 11: View of the altar in 1905, from The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916).

There were also three pulpits, [and] probably a table for Holy Supper. There was a baptismal font, which we do have a picture of (Figure 12), which is cool. But all of the other altar furniture is long gone. It’s lost. I didn’t even make an attempt to recreate that. I did look around at what a pulpit would have looked like, and all that I got were these massive things that had a staircase to ascend. And it wasn’t that. Proud says that there were three pulpits up at the front there, one by the vestry. So clearly he’s talking about something much smaller.

Figure 12: Baptismal font from the Temple, the only altar furnishing that has survived, from The New Church in Birmingham (Schreck, 1916).

You mention the vestry, and I couldn’t help noticing that in your video you very quickly zoom us through the last few rooms, and almost before we can get a clear view you grab our hands and yank us out. Was that intentional?

[Laughs] Yes. Quite intentional. The vestry was the last part I made. If it was the first thing that I had made it would have had a lot more detail. We do know a little about it. It was subdivided into two separate rooms, as it is in my model. It had a small library and a nice desk. I believe it had a fireplace in each room. So yes, it wasn’t because there was any deep meaningful reason to avoid the vestry, or it was a mystery. It’s more that it was the last part of the project and I was getting tired.

So is there any chance that you’ll go back and do the vestry?

I’ve thought about it. It wouldn’t be too hard to do. Put a few shelves in there, a table and a desk and chair . . . put those fireplaces in—those are pretty basic, and it would be easy to come up with a believable design.

Speaking of fire, the Temple itself almost succumbed to total destruction less than a month after its dedication! What can you tell us about that?

It’s interesting. At the time there were what were called “dissenting churches,” and the Unitarian Church was a big one in that group. There was a lot of anti-dissenting church feeling, to the point of riots and mobs. A couple of times, actually, a mob showed up at the New Jerusalem Temple with the intent of burning it down, because they associated it with the Unitarians. In fact, I believe it was Joseph Priestly, an influential early Unitarian, who attended the dedication of the Temple. There was the thought that maybe he was going to join and support the New Church. Before long, though, he actually pulled away and distanced himself from the New Church.4

Figure 13: Johann Eckstein, Rioters Burning Dr. Priestley's House at Birmingham, 14 July 1791. Wikimedia Commons. September 15, 2020.

This is a significant connection to mention, because the riots are known as “The Priestly Riots.” Can you tell us a bit more?

So, this mob shows up one day, and there are different versions of the story, but they have their torches out and are ready to burn the place down. Joseph Proud comes running out of the manse, which is right next door, and he scatters the money from the previous Sunday’s offering among the crowd. He informs them that they don’t support the Unitarians, they’re not a dissenting church, they’re fully in support of country and crown. The crowd then cheers and departs, yelling out, “The New Jerusalem Forever!”5

In a different version (the one told by Proud, so it might be more accurate), he borrowed the money from Samuel Hands, who happened to be at the manse at the time. And the irony of that is that Samuel Hands is the man who funded the church, and it was his going bankrupt in 1793 that lost the church building.

Figure 14: Engraving depicting Joseph Priestly’s house and laboratory in the aftermath of the riots. Philip Henry Witton, View of the Ruins of the Principal Houses destroyed during the Riots at Birmingham (London: J. Johnson, 1791). Aquatint. Library Company of Philadelphia: https://www.librarycompany.org.

1793? That’s such a short run for the Temple.

I have to say, I went into this with the thought that “this will be so cool to get to know the feel and history of a New Church building. Imagine the sermons that were preached there week in and week out, the holidays and baptisms, the funerals, the weddings . . .” You know, this rich history over the years and decades. And it was quite disappointing to find that it had remained a New Church building only for two or three years. I don’t regret going into this. It’s a fascinating piece of New Church history, but it’s a little sad.

Earlier you mentioned needing to learn about details by researching other buildings. If you had to estimate, what percentage of this project do you think is period sympathetic, rather than accurate reproduction? For example, the wall length is accurate reproduction, as is the height of the windows. But the chandeliers and columns are Georgian sympathetic. What’s your crude estimate?

From the outside, just looking at the structure, I think that’s maybe over 90% accurate. The same for the interior structure. I’m less clear on the materials and light sources. I didn’t even make an attempt at the altar furniture. So, I’d say the percentage drops quite a bit when we go inside. Particularly with the pews (Figure 15). I’ll be honest. There really are two styles of pews, and the other style I could have opted for would have been boxes with a little door. I opted for the bench style of pew because it seemed like it would be easier to design and produce in Blender. I don’t think it’s inaccurate—I think it’s a valid choice. But there are definitely other options that I could have gone with.

Figure 15: Joel Glenn’s 3D rendering of the pews, sanctuary, and gallery of the New Jerusalem Temple.

I’m glad you mentioned that, because when I looked at the pews, I thought to myself, “Wouldn’t they have doors?” That’s actually really important and can give insight into the worship life. It was not unusual or improper for churches of the time to have a subscription system.

If you look back at the descriptions, I do think there is mention of how much a seat costs.6 I forget how he phrases it, but there is that system in place where you pay your amount and you have your spot that you’re renting. Which would tend toward the box pews, I think.

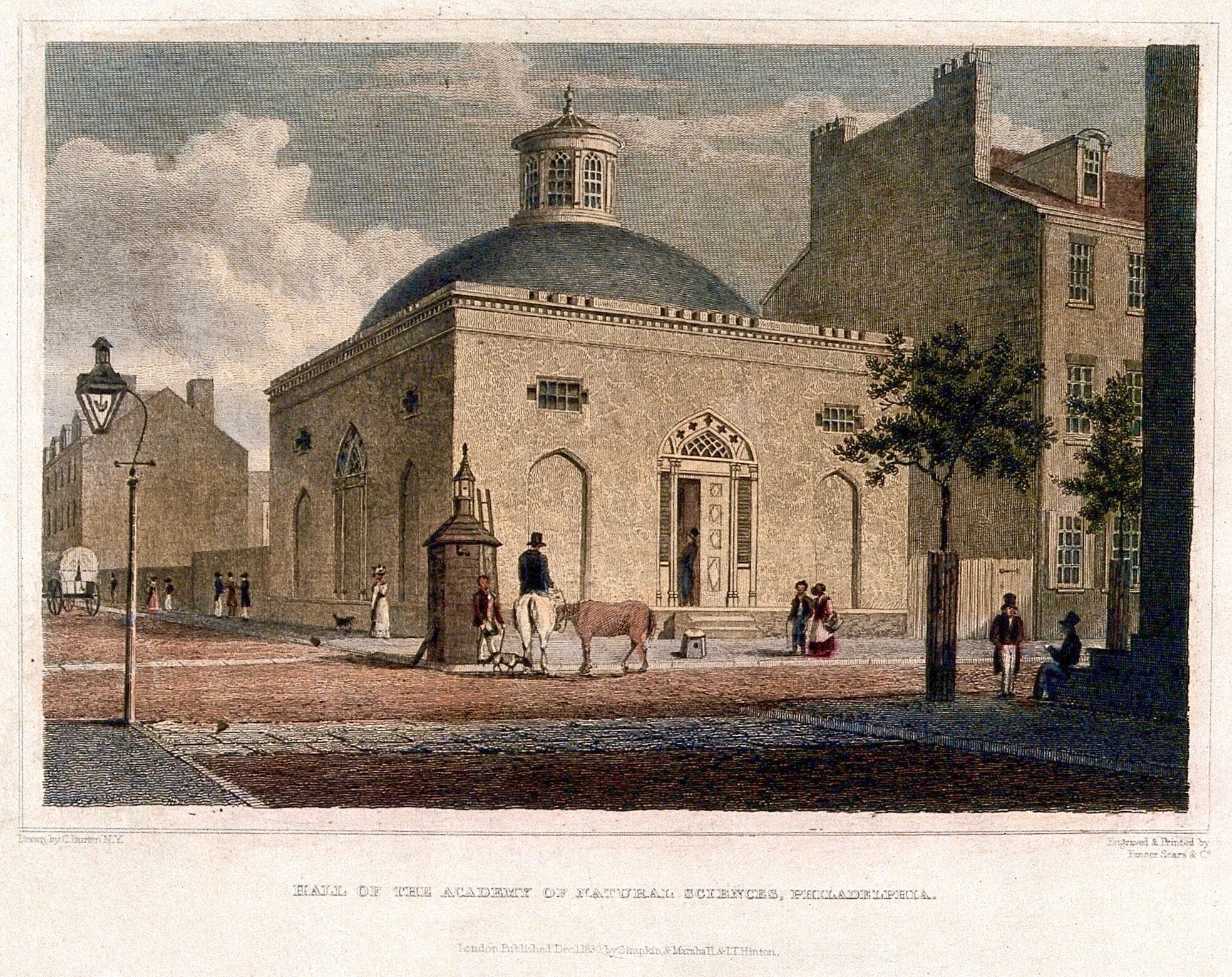

Years ago I attempted, with far inferior results, to do what you’ve done for the New Jerusalem Temple in Philadelphia (Figure 16). I mention it because I’ve experienced firsthand how unintuitive these 3D graphics programs can be.

I would definitely say I was not very efficient, especially at first. It takes so much time to get familiar with it and learn how it works. I remember when I first opened Blender I didn’t know how to do anything, and after just a few minutes I got frustrated and closed it. And that probably happened the first five times I opened Blender.

Figure 16: Engraving made in 1830 of the former New Jerusalem Temple in Philadelphia. By 1830 this building was the Academy of Natural Sciences. Colored engraving by Fenner Sears & Co., 1830, after C. Burton. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

I’m so glad you started using Blender. You’ve made such progress here in a relatively short amount of time. Now that you’ve got these skills, I have to know: what’s next?

Right now, I’m working on a model of my parents’ house, but that’s probably not interesting to most people. I would like to at some point take a look at the New Jerusalem Temple in Philadelphia. I know that’s the one you’ve worked on, and you’ve done a lot of my legwork for me, and so I’m just going to steal that from you.7

Figure 17: A behind the scenes look at the Temple within the Blender program.

Joel, let’s bring it back to Glencairn’s coin, because that’s how this all started. When you see the Kempson token now, what do you think? What is your appreciation for it? What’s your frustration with it? How do you feel about that coin now?

The coin is the sole contemporary image of the New Jerusalem Temple. I spent all this time going through trying to find contemporary pictures, and this is the only one that exists. So, my appreciation for that coin grew immensely. I’m frustrated that it’s not more detailed. There were many times when I would consult the coin and find it didn’t give the detail that I wanted. But at the end of the day it has a special place in my heart, because anything else is a copy or has additions. The closest we can get to actually seeing the Temple in its original form is the coin.

Figure 18: The Kempson token alongside Joel Glenn’s rendering of the New Jerusalem Temple.

To read more about the New Jerusalem Temple in Birmingham, visit www.NewChurchHistory.org

Figure 19: The Reverends Joel Christian Glenn (left) and Christopher Augustus Barber.

The Reverends Joel Christian Glenn (left) and Christopher Augustus Barber, pictured here on a road trip in 2008, have been friends since they first they met at Bryn Athyn College. Today they are both ordained priests in the General Church of the New Jerusalem, an international church with headquarters in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. They report that they are glad to have the opportunity to collaborate on this article for Glencairn Museum News. Though they are a world apart, with Joel serving as the assistant pastor of the New Church in Westville, South Africa, and Chris as a teacher of religion at the Academy of the New Church in Bryn Athyn, they are looking forward to working together on projects related to New Church history in the future.

References

Gyllenhaal, Kirsten. 2007. “First New Church Place of Worship in the World (1791).” Accessed March 15, 2020. http://www.newchurchhistory.org/funfacts/index0a10.html?p=115.

Proud, Joseph. 1790. Hymns and Spiritual Songs, for the Use of the Lord's New Church, Signified by the New Jerusalem in the Revelation. London: R. Hindmarsh.

Schreck, Eugene J. E. 1916. Early History of the New Church in Birmingham. London: New Church Press Limited.

Endnotes

1 In Proud’s words, “The members of the New Church can by no means use the publications now extant in their religious services.” (From p. 5 of Proud’s 1790 Hymn Book.)

2 A kind of divine symbolism described by Emanuel Swedenborg.

3 Schreck says he confirmed this through Proud’s memoirs.

4 Priestly penned a critique of Swedenborg’s theology, but it was lost when his house was burned in the riots (Figure 13). He later worked up a new version from a rough draft that he preserved.

5 On another occasion a mob managed to throw an incendiary projectile (sources call it a “grenade”) through the window, but it was extinguished before the fire could spread.

6 Schreck reports that “the prices of church sittings were decided upon, ranging from 2/6 to 1/– per quarter.”

7 Joel Glenn has done a number of digital recreations of art, including some work of his grandfather’s, Robert Glenn, who designed the mosaic ceiling in the Great Hall of Glencairn.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.