Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2021

This window in Glencairn’s Great Hall, made in the Bryn Athyn glassworks, features the Woman Clothed with the Sun mentioned in the Book of Revelation (12:1). Here the clouds of heaven may be seen just above the woman’s head (see also Figure 1).

Raymond Pitcairn began collecting medieval art in 1916 in order to provide inspirational models for the artists and craftsmen who were working on Bryn Athyn Cathedral. Pitcairn, who supervised both the design and construction of the Cathedral, was determined to build “in the Gothic way.” He assembled a highly skilled creative team in a series of workshops near the construction site, and made available to them his growing collection of medieval stained glass and sculpture. In the late 1920s, as the construction of the Cathedral began to draw to a close, work began on Glencairn, Pitcairn’s castle-like home. The same craftsmen now went about creating medieval-style artwork for the building in stained glass, stone, wood, and metal. Pitcairn’s favorite works of medieval art were incorporated into Glencairn’s Great Hall, placed in juxtaposition with original artwork made in the Bryn Athyn workshops.

Pitcairn placed a strong emphasis on the use of natural materials and actively solicited creative input from his craftsmen—practices that were popular during the American Arts and Crafts Movement. Glencairn’s decorative program included imagery—and even inscriptions carved in wood and set in mosaic—from both the Bible and the theological writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). According to stone carver Benjamin Tweedale, Pitcairn sometimes prepared his artisans for their work by asking them to read appropriate passages from the Bible or Swedenborg. They would then discuss the project and begin to formulate design ideas—“all leading to a steadfast expression of faith in stone” (E. Bruce Glenn, Glencairn: The Story of a Home, 1990, 59).

Figure 1: Imagery from the Book of Revelation was the inspiration for this window in Glencairn’s Great Hall: “Now a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a garland of twelve stars” (Revelation 12:1). Because the woman appears in heaven, in this window the clouds of heaven are depicted both above the woman’s head and below her feet.

An observant visitor to Glencairn will find numerous examples of the “clouds of heaven” in the building’s original artwork. Sometimes the clouds appear as an element of the overall composition (e.g. Figure 6), and sometimes the clouds seem to be used decoratively (Figures 10-15). Certainly the use of a symbol for heaven is consistent with the rest of the religious imagery in Glencairn. But what, exactly, was the inspiration for this “clouds of heaven” motif?

Figure 2: This reliquary box portrays the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket, who was murdered by the knights of the English King Henry II. As one of the soldiers severs the saint’s head, the hand of God appears from the clouds of heaven to signal that Becket’s martyrdom is divinely ordained (see also Figure 3). (Limoges, France. Circa 1220–30. 05.EN.112)

Figure 3: The hand of God descends from the clouds of heaven just above the altar of Canterbury Cathedral, where St. Thomas Becket is being martyred (see also Figure 2).

Pitcairn would likely have been familiar with the “clouds of heaven” from photographs and illustrations of medieval art in books in his personal library. According to Professor Michael W. Cothren, Glencairn’s Consultative Curator of Medieval Stained Glass, “Medieval artists commonly used a wavy, arching band of clouds (frequently placed across the corner of a rectangular composition) to show a separation between the earthly realm below and the heavenly realm above. For example, when a disembodied hand of God emerges from heaven to command or bless a situation taking place on earth [e.g. Figures 3 and 4], it is often overlapped by an arching band of ‘clouds of heaven.’ Sometimes the face of God appears within the cloud band. Sometimes angels swoop down toward earth underneath or emerging from the clouds.”

Figure 4: A 12th-century capital in Glencairn’s collection illustrates the biblical story of Lazarus and the rich man (Luke 16:19-31). This side of the capital depicts the death of Lazarus; the hand of God emerges from the clouds of heaven to bless the dying beggar. Read more about this capital here. (Monastery of Moutiers-Saint-Jean in eastern France. 12th century. 09.SP.94)

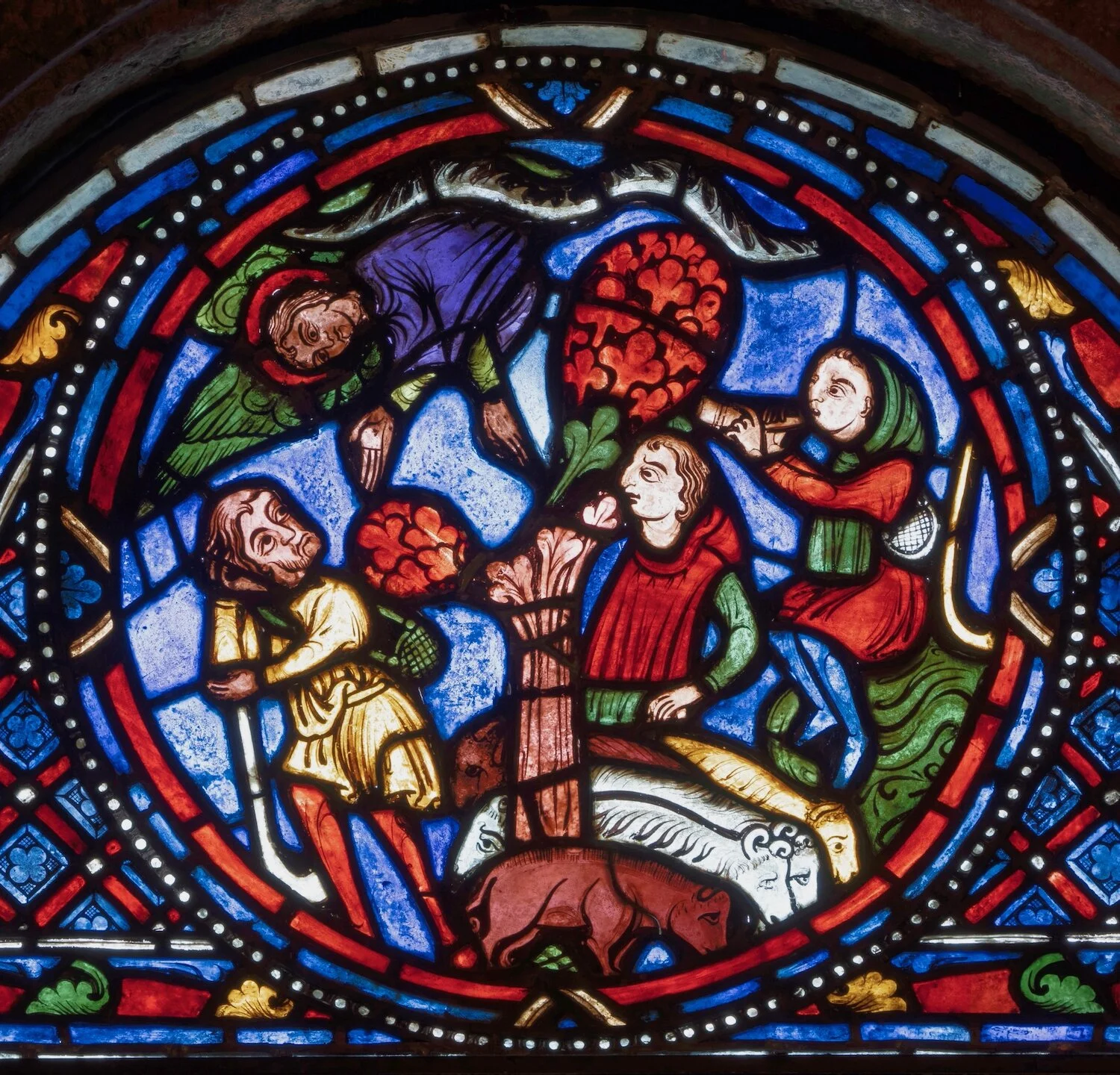

Figure 5: This 13th-century stained-glass roundel illustrates the Annunciation to the Shepherds (Luke 2:8-14), from the narrative of the Nativity of Jesus Christ. Here an angel with green wings and a purple cloak descends from a heavenly cloud and tells the shepherds that they will “find a babe wrapped in swaddling cloths and lying in a manger." (13th century. France. 03.SG.240)

Pitcairn would also have known about the “clouds of heaven” from objects in his own medieval collection, such as the enamel reliquary of St. Thomas Becket (Figures 2 and 3) as well as examples in sculpture and stained glass (Figures 4 and 5).

In art created for Glencairn—made in the Bryn Athyn workshops—the motif can be found in stained glass, stone and wood sculpture, and metalwork. Several examples follow below.

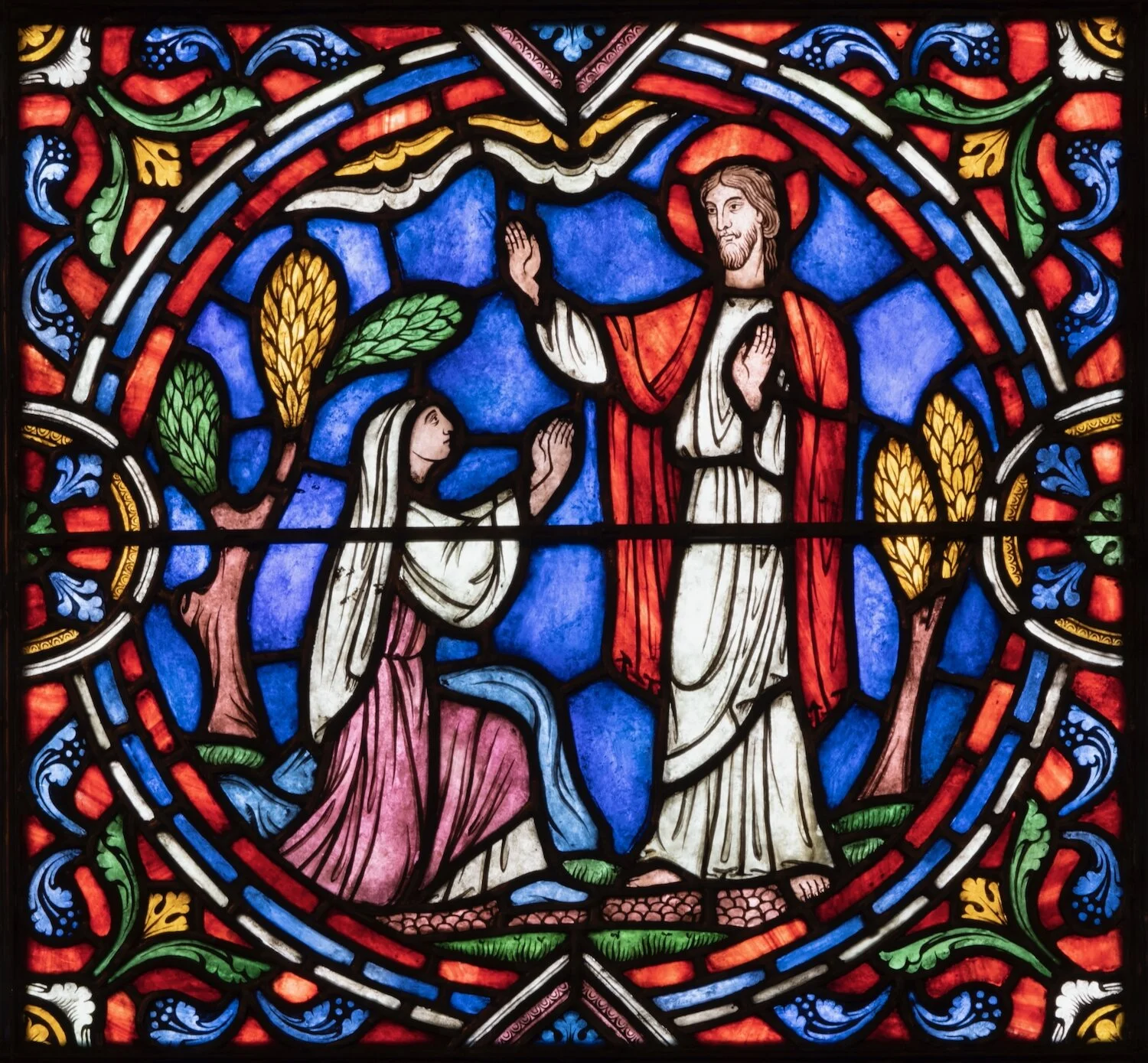

Figure 6: Glencairn’s fifth-floor chapel includes a stained-glass window with three scenes from the Easter story, all created in the Bryn Athyn glassworks. The central panel shows the resurrected Christ meeting with Mary Magdalene (John 20:13-16). The clouds of heaven may be seen just above the raised hand of Jesus.

Figure 7: This window, made for the east wall of Glencairn’s chapel, shows Jesus Christ surrounded by the disciples. The clouds of heaven are above them, in wavy bands of yellow and white.

Figure 8: This window in Glencairn’s Upper Hall illustrates the balance of power between branches of the federal government in the United States. Beneath the clouds of heaven motif is the Capitol building (center), the White House (left), and the Supreme Court building (right). Along the bottom is a quotation from one of the works of Emanuel Swedenborg: “There shall be justice among them” (Charity 130).

Figure 9: This granite relief sculpture, carved by Bryn Athyn craftsmen, decorates the monumental fireplace in Glencairn’s Upper Hall. It depicts the days of creation as described in the first chapters of the Book of Genesis. The clouds of heaven have been carved in a continuous band along the inside of the arch, above both the land and the sea. These images seem to illustrate the very first verse in the Bible: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). Read more about this sculpture here.

Figure 10: Lachlan Pitcairn’s infant crib was carved by woodworker Frank Jeck in 1922 in the Bryn Athyn woodworking shop. The top rail is carved with the clouds of heaven. Read more about this crib here.

Figure 11: The Monel metal posts that were designed for the third-floor balcony overlooking Glencairn’s Great Hall feature the clouds of heaven.

Figure 12: The balcony overlooking Glencairn’s Upper Hall includes the clouds of heaven along the bottom rail.

Figure 13: The clouds of heaven seem to be the inspiration for the decoration on this circular handle made for the copper doors in Glencairn’s Great Hall.

Figure 14: The Monel metal bosses on the bronze double door leading from the Cloister to the Great Hall may be an example of the clouds of heaven motif being used decoratively. (See Figure 15.)

Figure 15: One of the Monel metal bosses on the bronze double door leading from the Cloister to the Great Hall. (See Figure 14.)

(CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.