Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2013

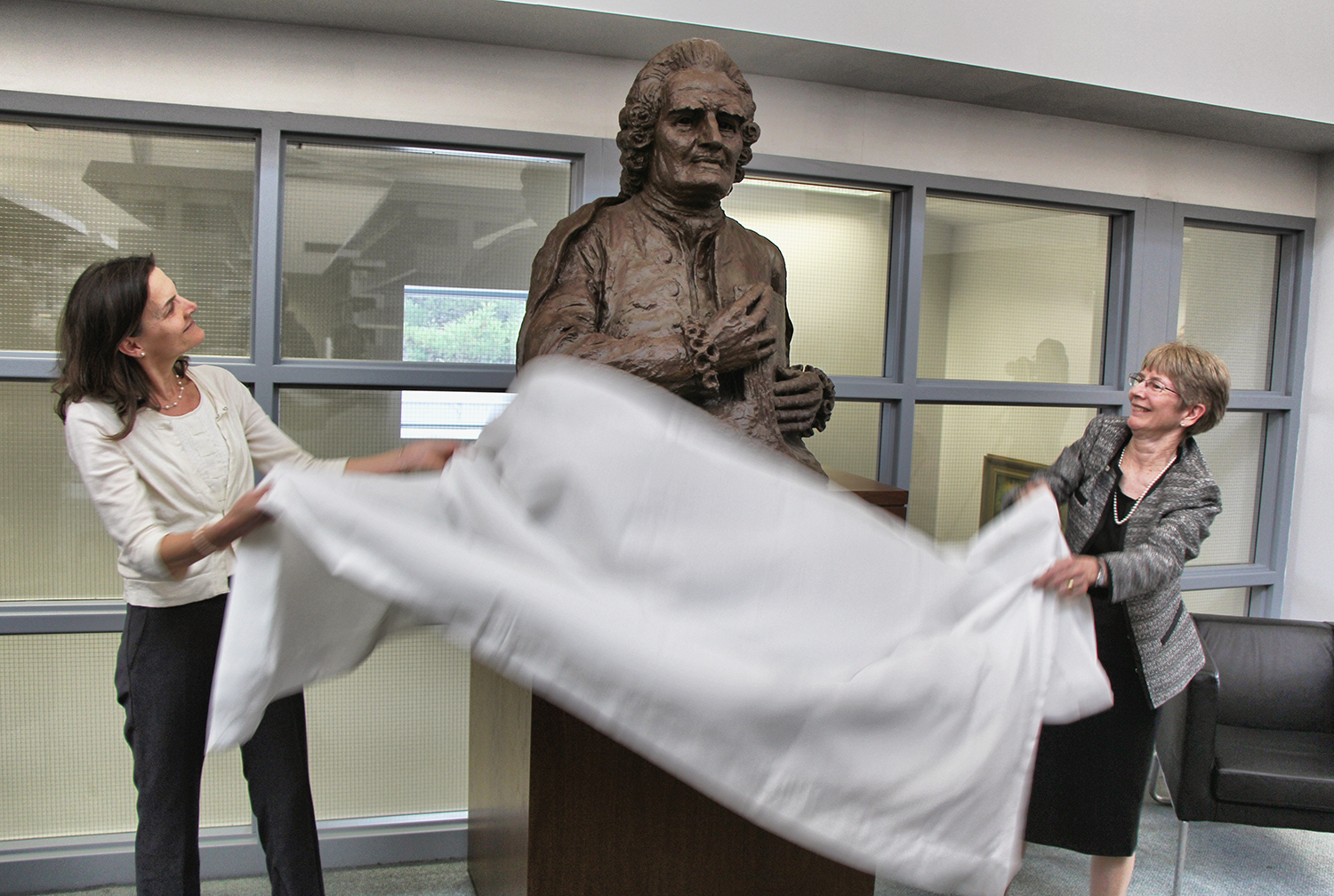

Dr. Kristin King, President of Bryn Athyn College, and Carroll Odhner, Director of the Swedenborg Library, unveil a plaster bust at the Swedenborg Library (2013).

The story begins in the early 1920s, when a portrait sculpture of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), a Swedish scientist, philosopher, and theologian, was created by the Swedish sculptor Adolf Jonsson (1872-1945). Jonsson, a reader of Swedenborg, made the bust over a five-year period, using as inspiration several portraits of the theologian in Gripsholm Castle and Nordiska museet. Jonsson had earlier created statues of other notables such as the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia, the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius, and Gustaf V, King of Sweden.

Figure 1: Plaster bust in the Swedenborg Library, Bryn Athyn.

According to Jonsson, his impression of Swedenborg evolved gradually over time: “I had imagined a picture of Swedenborg as a mystic, a spiritist and a seer, but the more I worked on it and the more I tried to become acquainted with Swedenborg himself, the better I realized that it could not be done. Essentially Swedenborg was not a mystic; he was a mathematician, a natural scientist, and it was his clear intelligence, his penetrating power of thought that I felt I ought to try to reproduce. It may be that I thus created something unexpected but personally I felt better satisfied” (The New Church Messenger, March 18, 1925).

Figure 2: The reinstalled bronze Swedenborg bust in Lincoln Park, Chicago (2012).

The bust was eventually commissioned in bronze by Mr. and Mrs. L. Brackett Bishop. It was placed on a tall pedestal in Lincoln Park, Chicago, and unveiled on June 28, 1924. The unveiling ceremony included an address by the Swedish minister to the United States, the reading of a letter from President Calvin Coolidge by a U.S. congressman, and the reading of “Swedenborg,” a poem by Edwin Markham. Some years later, most likely in commemoration of the 250th anniversary of Swedenborg’s birth (1938), the pedestal beneath the bust was engraved with a quotation by President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “In a world in which the voice of conscience too often seems still and small there is need of that spiritual leadership of which Swedenborg was a particular example. Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1938.”

Unfortunately, in 1976, 52 years after the dedication of the bust, it was stolen from its pedestal in Lincoln Park. According to an article in the Chicago Tribune, some five years earlier a bronze statue of Ludwig van Beethoven had also been stolen (“Statue in Lincoln Park Disappears; Police Baffled,” February 10, 1976). Since the most likely motive behind these thefts was the scrap value of the bronze, it seems unlikely that the statues will ever be recovered. For more than 30 years the pedestal stood in the park without its bust, still bearing an inscription with Swedenborg’s name and dates and the quotation from President Roosevelt. In place of the bust, the pedestal was topped with a small pyramid.

Figure 3: The plaster bust in the attic of Swedenborg Memorial Church, Stockholm.

In 2006 several staff members at Glencairn Museum decided to harness the power of the Internet and publish photos and documents about the missing bust, in the hope that more information about it might materialize one day. Remarkably, several years later Eva Bjorkström, a member of the New Church Society in Stockholm, saw the photos online and emailed the Curator of Glencairn Museum: “I read about the bronze bust of Swedenborg. It might amuse you to hear there is a plaster version, gigantic as I remember, up in our church attic. Painted green, and the nose is slightly chipped if I remember correctly” (Email communication from Eva Bjorkström to Ed Gyllenhaal, 11/26/08). A comparison of this plaster version with old photographs and measurements of the bust stolen from Lincoln Park revealed that it was the model made by Adolf Jonsson himself, from which the bronze was cast in the 1920s.

Over the next few years an international collaboration developed between the Chicago Park District, the New Church Society in Stockholm, and Glencairn Museum. It was decided to make a new bronze copy of the Swedenborg bust from the original plaster model in the attic of the church. Magnus Persson, an artist in Stockholm with expertise in making copies of historic sculptures, was hired to repair the plaster bust and oversee the production of the new copy in bronze.

Figure 4: "The whole plaster was a kind of ruin" (Magnus Persson).

According to Persson, the plaster original, which was nearly 90 years old, was in very poor condition: “It had cracked so that the whole back was only kept together thanks to the hemp lining inside the plaster. Fingers were missing, and parts of the wig curls were also missing or seriously damaged. The whole plaster was a kind of ruin. After the damaged parts had been fixed, and new fingers and curls remodeled, the plaster was transported to the foundry in Estonia. An exact wax copy was made of the bust. When the wax copy was finished the restored plaster bust was again in a damaged shape and cut into 4-5 different pieces. The wax version was embedded in a stable plaster coating containing different ingredients to make it strong and capable of standing the heat of melted bronze. The wax was melted, poured out and replaced by melted bronze. The technique is very old and called cire perdue (lost wax), as the wax mould is destroyed to unveil the cast item” (Email communication from Magnus Persson to Ed Gyllenhaal, 3/19/13).

Figure 5: The bronze bust being loaded onto a truck for shipment to the United States.

The bronze foundry in question was Ars Monumentaal, located in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia. Magnus Persson and his wife, Agneta Gussander, who is also an artist, transported the plaster bust of Swedenborg themselves—first in their own car, and then by ship. They were met at the port in Estonia by Vello Kümnik, the bronze casting master, and his daughter-in-law, who was able to speak languages other than Estonian and Russian. A total of three different trips from Stockholm to Estonia were necessary: one to deliver the plaster, a second to approve the wax model, and a third to transport the bronze and the plaster, now in several pieces, back to Sweden. Sadly, Vello Kümnik, the casting master, died soon after the casting was completed.

Figure 6: Magnus Persson prepares the bronze bust for shipment to the United States.

In February, 2012, the bronze bust of Swedenborg was shipped from the Stockholm studio of Magnus Persson to Chicago. A few months later it was reinstalled on the pedestal (sans pyramid) in the original location in Lincoln Park, east of North Lake Shore Drive and south of Diversey Harbor. Last summer the plaster version of the bust, restored once again to its original condition and painted to resemble bronze, was shipped from Stockholm to the Swedenborg Library in Bryn Athyn—a new and most appreciative home.

This international effort to “right a wrong” required the generosity and cooperation of a number of people. In many places the monetary value of copper, lead and bronze has led to an epidemic in the theft of public sculptures, and not all such stories end as happily as this one.

(CEG)

Photos courtesy of Julia Bachrach, Eva Bjorkström, Ed Gyllenhaal, and Magnus Persson.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.