Glencairn Museum News | Number 9, 2016

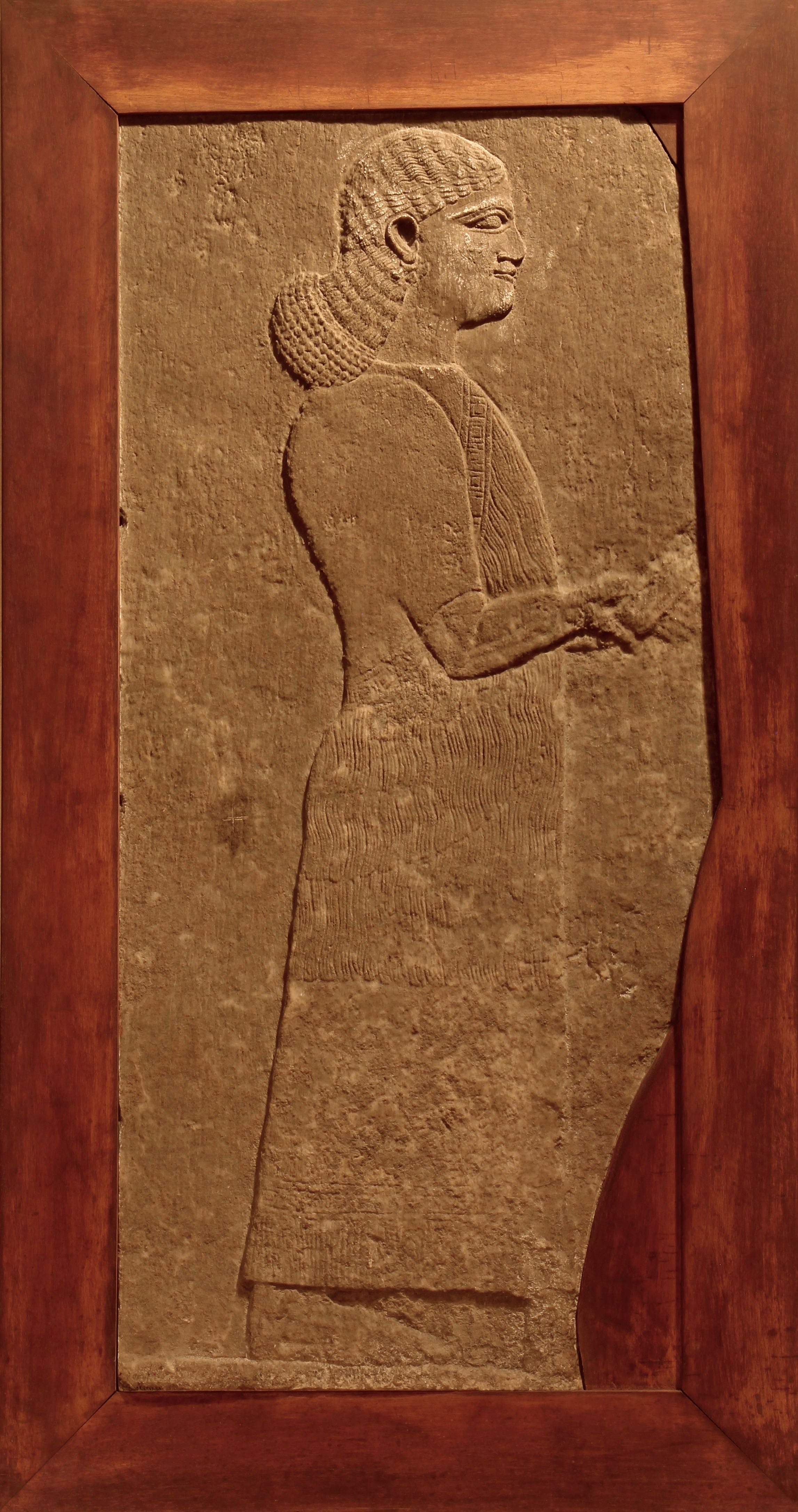

Figure 1: Head and shoulders of a genie, Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, Iraq. In the 19th and early 20th centuries Assyrian reliefs were often cut down and fitted into a wooden frame to signal their worthiness for purchase or display. (09.SP.1550; 61 x 54 cm)

In February of 2015 a video appeared online showing men, dressed in black, wielding hammers, drills, and chainsaws. Their targets were large free-standing plaster casts and, in one particularly shocking image, the face of a colossal stone human-headed bull. The location of the destruction was the Mosul Museum, the second largest museum in Iraq. The perpetrators were fighters for ISIS, and the targets were the monumental material remains of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which, between the ninth and seventh centuries BC, had ruled what was then the largest empire the world had yet seen from its heartland in northern Iraq. The royal cities of that empire have also been targeted by ISIS: they bulldozed the remains of Nimrud, the capital city of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, and have released statements threatening to damage Nineveh, another capital.

This destruction horrified the Western public—as it was most likely intended to do. It also renewed Western interest in the empire whose remains had so enraged the Islamic State. The Neo-Assyrian Empire fell more than two and a half thousand years ago, but its surviving material remains still had the power to provoke and enrage the latest conquerors of Assyria.

When they were rediscovered in the mid-19th century, the palaces of the Neo-Assyrian Empire were excavated primarily by English, French, and German powers. Monumental palace art was removed, labelled, and shipped back to Europe, part of a project of imperialist nation-building and competition between the Western powers for influence in the then-Ottoman Middle East. Although the greater part of material remains were sent to the great national museums of London, Paris and Berlin, a number of fragments and individual slabs were given to schools or universities, or as gifts to private individuals. Subsequently a number of these fragments found their way onto the antiquities market, which is how Glencairn Museum came to have its own selection of Assyrian reliefs, shallow carving on limestone slabs once mounted on palace walls, purchased by Raymond Pitcairn over the course of the 1920s.

The Glencairn reliefs, although a small collection of five fragments, are nonetheless an exceptionally well-chosen group, representing diverse aspects of the religion, ideology, and artistry of the Assyrian Empire and typifying the development of the genre over time. As we consider what these reliefs show, and how and why they came to be in the condition and the location they are today, we will begin to understand the variety of ways that these powerful images have been interpreted in ancient and modern times. ISIS’s destructive antipathy is but one of many responses to Neo-Assyrian art.

The Glencairn Reliefs

Glencairn’s five reliefs come from the reigns of three different Neo-Assyrian kings and two different Neo-Assyrian capital cities (Markoe 1983, 1-5). The oldest two reliefs are also the collection’s largest and best-preserved, two pieces from the now-bulldozed Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC) at Nimrud. They each depict, though on different scales and in different poses, a supernatural figure known in Akkadian as an apkallu, usually referred to in English as a “genie.” They are of human appearance in all but their large, bird-like wings, and their helmets: the horns that curve inwards along the side indicate that the wearer is a divine being, a tradition in Mesopotamian iconography that reached back more than two thousand years before the carving of these images.

Figure 2: A kneeling genie, Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, Iraq. (09.SP.1549; 77 x 68.5 cm)

In one of the fragments, we see only the exquisitely carved head and shoulders of the genie (Figure 1). In the other, the genie kneels before a stylized image of a palm tree, one muscled leg visible from beneath the short tunic he wears under a long sheepskin robe (Figure 2). His hands touch two of the tree’s flowers in what is likely a symbolic gesture of fertilization.

Winged genies from Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace are an unsurprising find in a museum—simply because there were a lot of them to go around. The enormous, many-roomed palace was covered in over two hundred representations of these apotropaic figures, depicted in a small handful of standardized types and poses (of which we see two at Glencairn). They literally wrapped the palace in their protection, mediating between the king and the gods and protecting him from malign influences, human or superhuman. The repetition of the same images was mirrored in the repetition of one text across the palace walls: the so-called Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II, carved in Akkadian cuneiform, was banded around the interior walls, sometimes overlapping the figures.

Despite the repetition, it is important not to presume that repeated “types” are necessarily identical. A 2013 article in Glencairn Museum News on a project to digitally recreate Ashurnasirpal II’s palace (for which Glencairn’s reliefs were imaged) discusses how subtle differences in dress or pose may have been missed in previous catalogs, which extrapolated from detailed examinations of only a few examples of each type. This digitization project was underway prior to the rise of ISIS, but has taken on new urgency and value in the years since.

The next Glencairn fragment can be dated, from style and context, to the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BC), from the Central Palace at Nimrud, his own royal seat. The relief shows a beardless male figure standing, one hand folded across the other (Figure 3). As with the genies, iconographical hints allow the scholar to interpret who this figure is and what he is doing, even now, devoid of any of its original context. He is a human and a eunuch, apparent from his beardless, double-chinned face. Eunuchs like the one depicted here were significant palace functionaries in most periods of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. His clasped hands also allow us to extrapolate aspects of the scene beyond the fragment we have here: the gesture is one that is made by attendants who receive the king, which we can assume he once did. This is another major theme of Assyrian reliefs: the king and his officials in the midst of ritualized ceremony. The ritual activity of the court, which took place within these very palaces, was reproduced in stone on its walls.

Figure 3: A eunuch royal attendant, Central Palace of Tiglath-Pileser III, Nimrud, Iraq. (09.SP.1551; 89.5 x 42 cm)

Figure 4: Assyrian soldiers in a chariot, North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, Iraq. (09.SP.1553; 19 x 27 cm)

The newest fragments in the collection date from the reign of Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC) from yet another palace, the North Palace, and the new capital city of Nineveh. The first fragment (Figure 4) can be identified as an image of soldiers in a chariot (the close grouping and overlapping arrangement is only used for figures riding in these vehicles). Because their weapons are not raised, it is clear they are not on their way to battle, but part of a victory celebration. The final Glencairn relief (Figure 5) shows three men standing against a backdrop of palm trees, sacks thrown over their shoulders. This is also an image of the aftermath of war, but these men are prisoners rather than celebrants. The fragment belongs to the reliefs from an interior courtyard that deal with the defeat and capture of Chaldeans (note their headbands and thick, ropey hair, signals of their ethnicity) after a battle in the marshes around Babylon. These prisoners are being deported from their homes to be resettled elsewhere in the empire. The sacks they carry are the possessions they take into exile. Warfare and its often brutal aftermath was another major theme of the Assyrian palace.

Figure 5: Chaldean prisoners of war facing deportation, North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, Iraq. (09.SP.1552; 31 x 28.5 cm)

These Ashurbanipal fragments are smaller than the others in real terms, and the figures are carved on a much smaller scale. Although Assyrian reliefs in all periods could be arranged in various ways, Ashurbanipal’s palaces, in contrast to those of his predecessors, exhibit densely packed, multi-register reliefs, with numerous “groundlines” allowing them to tell visually and narratively complex tales that represent both space and time. To allow for multiple registers within one wall slab, the individual figures are carved on a smaller scale than the genies or the eunuch of earlier periods, who generally occupied all of or roughly half of the height of a wall slab.

Over the course of the Neo-Assyrian period, the themes and methods of palace relief programmes had changed in a way that is perfectly represented in the Glencairn sampling: while Ashurnasirpal II’s palace is characterized primarily (though not exclusively) by images of supernatural beings and representations of religious ritual, Ashurbanipal and the later Assyrian kings featured far fewer divine beings and larger, longer, and more narratively and visually complex images of warfare and its aftermath. Thus Glencairn can boast “typical” fragments, demonstrating the strengths of each period.

Although Ashurbanipal did not blanket his palaces with protective genies, it may be that his more militaristic subject matter ultimately served a similar function: his reliefs testify to his success in the duties that the gods tasked him with (expanding and defending Assyria, capturing those Chaldeans and celebrating in those chariots). The narrative images were a testament in stone that spoke to the gods, just as the genies spoke to them, on behalf of the palace’s human residents.

Framing the Assyrian Past

Looking at the images of the Glencairn reliefs above, the reader might have noticed that they are suspiciously neatly broken and that they are displayed in period-inaccurate wooden frames or mounts. These frames, and the neat shapes they encompass, are something of a period piece in themselves, a relic of how the reliefs were perceived by their excavators and disseminators in the 19th and early 20th century.

Assyria’s Victorian re-discoverers took a largely dim view of the reliefs’ artistic worth: Sir Henry Rawlinson, one of the “fathers” of Assyriology and an excavator of Nineveh, described the reliefs as “curious, but I do not think they rank very highly as art.” He rhetorically asked, “Can a mere admirer of the beautiful view them with pleasure?—certainly not and in this respect they are in the same category with the paintings and sculptures of Egypt and India.” Asked what he compares them against, Rawlinson gives his standard for aesthetic value as the Elgin Marbles (Larsen 1996, 102-103).

The idea that Assyrian art was not merely different from the Elgin Marbles, and the Western artistic tradition derived from them, but inferior, influenced how reliefs were exhibited. Reliefs destined for major museums were kept substantially intact, but those given to smaller institutions or to private individuals were often deliberately “cut” into more palatable shapes, like Glencairn’s western-style head-and-shoulders “portrait” made out of a full-body figure of a genie. The other Glencairn reliefs appear to be accidental rather than deliberate fragments, but they were clearly shaved down when they were distributed or sold to more appropriately fit a frame, which would signal their worthiness for purchase or display.

Reliefs in museums today were also often modified by their excavators simply in order to solve the very difficult question of how to transport such large and heavy items: those sent to the British Museum were “shaved” thinner at the back, so that they would weigh less. French excavators sawed their colossal bulls into four pieces for transportation back to Paris. In 1855, boats carrying artefacts destined for the Louvre were attacked and sunk into the Tigris, never to be recovered (Potts 2012, 52). The bright paint that would have covered the reliefs in ancient times was largely gone even when first excavated, but exposure to light and overzealous museum cleaning has further erased it (Verri et al 2009, 61).

Figure 6: A drawing by an excavation artist dramatizing Nineveh excavator Austen Henry Layard’s supervision of the removal of a colossal bull. Though intended as an objective record of the event, it is clear that the image also tells us a great deal about how British excavators in Iraq saw their role vis-a-vis the Iraqi workers they employed. (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Destroying Art and Artefacts

Other damage to the exhumed carvings was ancient—and intentional. When the Assyrian Empire fell to a coalition led by the Medes and Babylonians, its conquerors ritually destroyed the faces and sometimes hands of images of the king, his queen, and significant military figures. The destruction of defeated enemies’ material representations was also practiced by the Assyrians. Ashurbanipal boasted of his revenge against a statue of a long dead enemy king: “This image of Hallusu, this king of Elam, who plotted evil against Assyria, [. . .] made hostile acts against Sennacherib, king of Assyria, my grandfather—his mouth which sneered, I cut off, his lips which spoke insolence, I severed, his hands which grasped a bow to attack Assyria, I broke away.” The practice was so common that when archaeologists find Mesopotamian statues, they are almost always headless, and the heads, if found, often have lips or noses deliberately damaged (May 2014, 702-719; Akkadian translation after May).

The purpose of such iconoclasm was likely to make the individual represented in the image “fully dead.” Not coincidentally, the noses and lips which were so often specifically targeted were believed to be the features that linked humans to the breath of life (Figure 7). The famous “Banquet Relief” (a plaster cast of which is on display in Glencairn’s Ancient Near East gallery), which depicts Ashurbanipal and his queen reclining in their garden, raising bowls to their lips, has been damaged—both the couple’s faces and their bowl-holding hands—effectively cutting them off from the sustenance they once drank.

Figure 7: The damage to the face and hands of this genie in Glencairn’s collection may be an example of deliberate destruction, although it would be only the second known example of a genie being targeted. It is not always possible to tell whether damage was intentionally inflicted.

Ashurbanipal, again discussing his own behavior towards his enemies, explains the disaster that would follow destruction of images just like the ones we have in Glencairn today: “I removed protective figures, guards of the temple as many as there were . . . graves of their earlier and later kings, who did not obey Ashur and Ishtar, my lords; who made my royal forefathers tremble, I dug out, I demolished, I exposed to the sun. Their bones I took to Assyria; I inflicted restlessness on their ghosts. I deprived them of funerary offerings and water libations” (May 2014, 720; Akkadian translation after May). The protective figures Ashurbanipal refers to would have been the enemy’s equivalent of the genies we see in Glencairn, and, although the latter section refers to corpse desecration, a similar fate would befall individuals whose statues were destroyed. The monumental image, in Mesopotamia, was not a mere copy of something real, but rather a manifestation of the real.

The iconoclastic destruction Assyrian reliefs sustained in ancient times might be said to enhance our experience of them today, allowing us to see in them the weight of history and adding to our understanding of the relationship these ancient societies had to images. In contrast, modern destruction of ancient artefacts, like ISIS’s power-drilled Assyrian bull, can rarely be viewed so sanguinely, even if it is worth remembering that ancient artefacts often come to us after or even through deliberate destruction. We can never experience the objects of the ancient past as their creators meant them to be experienced because we lack not only the physical context (in this case, the palace the reliefs were an integral part of) but also the cultural and spiritual context.

When ISIS destroys Assyrian statues they do not, as Ashurbanipal did with Hallusu, talk about punishing the individual manifested in that statue. Instead they frame their destruction as a matter of preserving their own religious piety, as one spokesperson declaims in the video celebrating Nimrud’s destruction: “These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah . . . We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them.” (For the sake of accuracy, it should be pointed out that the Assyrians did not, strictly speaking, worship the apotropaic statues in the Nimrud palaces, and that this pious rhetoric might just be a little dishonest: it seems to be the case that ISIS destroys only the “idols” that are too large to easily sell on the black market.)

Yet, whatever the logic behind it, ISIS participates in the same tradition of ritualistic iconoclasm that Assyria and its contemporaries once did, making warfare against the statues and monuments of the enemy. ISIS might be the last major remaining cultural group to credit the Assyrian genies with the power and danger that the Assyrians themselves would have agreed they held.

The Glencairn Context

The five Assyrian reliefs in Glencairn’s Ancient Near East gallery were probably all purchased by Raymond Pitcairn, who built Glencairn between 1928 and 1939, which he intended as a home for his family. Raymond and his younger brother, Theodore, were dedicated members of the New Church (Swedenborgian Christian). The attitude of the New Church towards religions of the past could not stand in starker contrast to the attitude of ISIS. Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), a Swedish scientist, philosopher, and theologian whose teachings form the basis of the New Church, believed, in contrast to most in his time, in a succession of “true churches,” each possessing their own real religious knowledge and real connection to God. Assyria would have fallen under the scope of Swedenborg’s Antiqua Ecclesia, the second of the five true churches, which was centered in Egypt but encompassed the various traditions of the ancient world (Gyllenhaal 2010, 179). Thus the Assyrians were, in Swedenborgian tradition, respected as a potential source of real religious truth from a previous era.

Such religious motivations were likely a key element in the Pitcairns’ interest in acquiring artefacts from Assyria. The first Assyrian reliefs in Bryn Athyn were actually purchased by Raymond Pitcairn’s brother Theodore.1 A pair of standing genies from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, these objects were offered to Raymond for $22,000, of which half was to be paid up front, and half within a year, a common practice at the time. (In contrast, Glencairn’s cuneiform tablets, purchased in the late 1920s, sold for between $3 and $12, and even the large and well preserved cylinder of Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar cost only $1200.) Even Raymond, a wealthy art collector, felt unable to pay the full amount because of the number of other purchases he was carrying, and encouraged Theodore to pursue the opportunity instead.2 Theodore did so, and installed the genies in the “porch of his studio at Bryn Athyn.”3 These reliefs are the only ones not still in Bryn Athyn, having been sold to another private collection in 1975 (Von Bothmer 1990, 36-37). Raymond purchased his own reliefs in 1926 (the kneeling genie of Ashurnasirpal II and the eunuch attendant of Tiglath-Pileser III) and 1927 (the genie “portrait” of Ashurnasirpal II and, from a different dealer, the small Ashurbanipal chariot fragment—purchase information for the final Ashurbanipal fragment has not been found).

As is indicated by the prices paid, these were high status acquisitions. The kneeling genie was the partner of one then being exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Leonard Woolley’s discovery of the magnificent Royal Cemetery of Ur in 1922, though a much earlier and more southern site than the Neo-Assyrian capitals, had contributed to an upsurge of interest in Mesopotamian art and artefacts. In the 1920s, as the Pitcairns were building their Assyrian collection, art deco buildings with architectural structure or decorative programmes inspired by Neo-Assyrian palaces were in construction around America, including (among others) the Pythian Temple in New York (1927; Figure 8), the first skyscraper state capitol building at Lincoln, Nebraska (1928), the Medinah Athletic Club in Chicago (1929), the gaudy and particularly palatial Samson Tire Factory in Los Angeles (1930), and the Valley Life Sciences Building in Berkeley (1930). Assyrian art was in vogue.

Figure 8: Heads inspired by Neo-Assyrian colossal bulls (and iconographically similar to the genies at Glencairn) on the Pythian Temple in New York City, a lodge for members of the fraternal organization The Knights of Pythias. The art deco building drew heavily from on-trend Egyptian and Assyrian artistic motifs. (Photo by Beyond My Ken, via Wikimedia Commons.)

It also seems that the Pitcairns may have been interested in pursuing the purchase of Assyrian reliefs because they had (perhaps unlike Rawlinson) a personal fondness for the works as art. Like Theodore, Raymond chose to hang the reliefs in his own home (rather than loaning them to the Academy of the New Church’s museum, which was just across the street). We know that three of the reliefs (the kneeling genie, the head and shoulders of a genie, and the soldiers in a chariot) were displayed in Raymond’s personal study (suggesting a personal fondness), and the eunuch royal attendant was given a place of honor in the Great Hall of Glencairn. A recessed space, seemingly originally intended to hold the head of the genie but ultimately covered over by the royal attendant relief, was built into the wall of the Hall (Figure 9). Raymond wanted his reliefs to truly architecturally “belong” in his home as they once had in the palaces for which they were designed.

Figure 9: Raymond Pitcairn chose to exhibit one of his Assyrian reliefs in the northwest corner of the Great Hall of Glencairn: a royal eunuch attendant from the Central Palace of Tiglath-Pileser III (Figure 3). However, originally the space seems to have been prepared for the square frame of the smaller relief of the head of the genie from the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II (Figure 1). A square, recessed niche is still visible above the open doorway. At some point the relief was removed, and now all five Assyrian reliefs are on exhibit in Glencairn's Ancient Near East gallery. Pitcairn also displayed three Assyrian reliefs in his personal office in Glencairn's basement.

Today, re-contextualized once again as part of a museum exhibit, the Assyrian reliefs in Glencairn partake of the strange and the familiar. They unite the viewer with an empire long gone, but recently and strangely politically relevant. In their original role, they worked magic on behalf of the Assyrian king and communicated to his gods on his behalf. When the Assyrian Empire fell they were cut off from their magical and life-giving power by conquerors who sealed them in under palatial rubble. Rediscovered in the 19th century, they were jealously fought over by European powers, each of whom wanted the museum collection that testified to their own imperial power, even as the coveted artefacts were sneered at for their failure to be more like Greek art. To wealthy Swedenborgian collectors in the 1920s, they were valuable clues to ancient, and truthful, religious knowledge and, on a more practical level, an imposing, stylish decoration for Glencairn’s Great Hall. To ISIS, they are idols to be destroyed (if only because they cannot be sold for profit). All these interpretations and interactions inform how the visitor to Glencairn might experience the reliefs today: in their life as objects, these reliefs have acquired and hold simultaneously all these meanings.

Eva Miller

Senior Scholar at Hertford College, University of Oxford

Endnotes

1 On the purchase history and original display of the reliefs, I am indebted to research by Ed Gyllenhaal and Kirsten Gyllenhaal, received in personal communication, September 8th, 2016.

2 Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Theodore Pitcairn. 2 February 1923. Glencairn Museum Archives, Bryn Athyn, PA.

3 Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to R. D. Barnett. 28 October 1959. Glencairn Museum Archives, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Further Reading

Bahrani, Z. 2003. The Graven Image: Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Barnett, R. D. 1976. Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668-627 B.C.). London: British Museum Publications.

Cohen, A., and S. E. Kangas, eds. 2010. Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography. Hanover, New Hampshire: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College.

Englund, K. 2016. “Nimrud NW Palace.” http://cdli.ucla.edu/projects/nimrud/index.html

Gyllenhaal, E. 2010. “From Parlor to Castle: The Egyptian Collection at Glencairn Museum.” In Millions of Jubilees: Studies in Honor of David P. Silverman, edited by Zahi A. Hawass and Jennifer Houser Wegner, 175–203. Cairo: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités.

Larsen, M. T. 1996. The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land, 1840-1860. London: Routledge.

Markoe, G. 1983. “Five Assyrian Relief Fragments in the Glencairn Museum.” Source: Notes in the History of Art 2 (4): 1–5.

May, N. N. 2014. “‘In Order to Make Him Completely Dead’: Annihilation of the Power of Images in Mesopotamia.” In La Famille Dans Le Proche-Orient Ancien: Réalités, Symbolismes, et Images : Proceedings of the 55th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Paris, 6-9 July 2009, edited by Lionel Marti, 701–26. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Oates, J., and D. Oates. 2001. Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq.

Porter, B. N. 2009. “Noseless in Nimrud: More Figurative Responses to Assyrian Domination.” In Of Gods, Trees, Kings and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola, edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd, and Raija Mattila, 201–20. Helsinki: Finnish Oriental Society.

Potts, D. T. 2012. A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Robson, E. 2016. “Assurnasirpal’s Northwest Palace.” http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/northwestpalace/

Russell, J. M. 1997. From Nineveh to New York: The Strange Story of the Assyrian Reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum and the Hidden Masterpiece at Canford School. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Verri, G., P. Collins, J. Ambers, T. Sweek and St J. Simpson. 2009. “Assyrian colours: pigments on a Neo-Assyrian relief of a parade horse.” BM Technical Research Bulletin Vol. 3: 57-62.

Von Bothmer, D. 1990. Glories of the Past: Ancient Art from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.