Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2021

A 3D digital reconstruction of the Cherry Street Temple in Philadelphia by Rev. Joel Christian Glenn. (YouTube video with narration).

Figure 1: The Charter of the Academy of the New Church, granted in 1877 by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Academy of the New Church Archives.

Glencairn Museum is the steward of an extensive collection of religious art and artifacts from around the world. This invaluable member of the Academy of the New Church family is fueled by a mission to “engage a diverse audience with the common human endeavor to find higher meaning and purpose in our lives.” This mission continues the legacy of the faith of the founders of the Academy of the New Church, a faith that is ever-present in spirit of Glencairn today. Founded in 1878, there has been an Academy museum for almost as long as there has been an Academy of the New Church—first known as the Academy Museum, and now as Glencairn Museum.

Academy founder William Henry Benade (1816-1905), an influential New Church priest and teacher, saw the value of learning through artifacts during his 1877-1879 world tour undertaken with John Pitcairn (1841-1916), the industrialist father of Raymond Pitcairn, who later designed and built Glencairn. (1) Their tour of Europe, Egypt, and the Holy Land (Figure 2) convinced them that a museum would bring to life lessons about ancient religion and connection with the divine, both important aspects of the New Church worldview.

Figure 2: John Pitcairn (far left) and Rev. William Henry Benade (seated) photographed outside of Jerusalem, 1878. Academy of the New Church Archives.

The New Church faith, founded on the insights of Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), was the fuel that drove most of the designs of the founders of the Academy of the New Church, the Bryn Athyn community, and the church that continues to guide and inspire them both. The Academy has not always been in Bryn Athyn; initially it was chartered to be established within the City of Philadelphia (Figure 1).

Figure 3: 110 Woodstock St., Philadelphia. This four-story brick house was once the private residence of Rev. William Henry Benade. During that time, it also served as the home of the Academy’s theological school and the Academy Museum. Afterwards it became a medicinal dispensary, which would later be relocated to the deconsecrated Cherry Street building. Photo taken by Christopher Augustus Barber.

The Academy Museum’s first home, for want of space in the school building that formed the nucleus of the Academy, was situated in Benade’s residence at 110 Friedlander (now Woodstock) Street (Figures 3, 7). The place where spiritual thought was developed, preached, and studied, both devotionally and academically, was just around the corner at a building known by some today as the “Cherry Street Temple” (Figure 4). In this Temple the Academy’s spirituality took root and was nourished.

Figure 4: Exterior photograph of the Cherry Street building at the northwest corner of Cherry and Lambert streets in Philadelphia, taken sometime after 1862. Academy of the New Church Archives.

This building, a stone structure with a compellingly arched roof, is largely forgotten today. Even histories written by subsequent owners and journalists have failed to report its original purpose, declared at the laying of its cornerstone in 1856 by Rev. Benade:

“This stone is laid in the foundation of a building now to be erected and hereafter devoted to the great and holy use of instructing and educating children and youths according to the heavenly doctrines of the New Jerusalem . . .” (2)

Even many people connected with the New Church and the Academy today have at best a vague recollection of some nebulous “Cherry Street” establishment. And yet, whether it is known or not, its energy vibrates within the life of Bryn Athyn, the Academy, and Glencairn today, most palpably through faith and education.

Figure 5: 1857 bird’s eye view of Philadelphia by John Bachmann. Note its location in relation to St. Clement’s Episcopal Church and its distinct arched roof.

Only one photograph of the exterior of the Cherry Street building as it was during its years as a church is known to exist (Figure 4). It was, however, captured with a relatively faithful, if low resolution rendering in this 1857 bird’s eye view of Philadelphia by John Bachmann (Figure 5). (3)

Among the thousands of artifacts that Glencairn preserves and interprets are many that do not have the opportunity to be exhibited very often. Some of these are from this primordial period of the Academy. They are artifacts that get to the very heart of the mission that drives the Academy and Glencairn today.

Figure 6: Interior photograph of the Cherry Street building, taken in 1882, modified to highlight objects still in existence today. Academy of the New Church Archives.

This photograph (Figure 6), taken in 1882, has four items highlighted: one altar, two chairs, and one baptismal font. These objects formed an ensemble of liturgical furniture designed to aid in the worship life of the community. Since this photo was taken, the Academy and the church have moved in tandem from their original place in Philadelphia to Montgomery County, (4) and these pieces have been preserved along the way. They are currently under the care of two members of the Bryn Athyn Historic District: Glencairn Museum and Bryn Athyn Cathedral. These artifacts are important, tangible links to the humble and optimistic beginnings of a movement that yielded both Glencairn and the Cathedral.

Figure 7: The Cherry Street building can be seen at the corner of Claymont and Cherry in this Hexamer and Son insurance map from 1887. Note also 110 Friedlander, home of Rev. William Henry Benade, the theological school, the library, and the museum. The Academy Girls School began as a semi-independent operation at 2040 Cherry Street. Also, in the bottom left, is St. Clement’s Episcopal Church, built the same year as the Cherry Street building. St. Clement’s later bought 110 Friedlander and the Cherry Street building from the New Church Society in 1888, and converted them into a dispensary and a hospital, respectively. St. Clement’s is still an active church today.

Built in 1856 and run as a school and a church, the operation at Cherry Street was presided over by Benade for two chapters of its existence. The first was brought to an abrupt halt in 1861 by economic difficulties resulting from the Civil War. The second started with renewed vigor in 1877 after his tenure in Pittsburgh, where he became reacquainted with John Pitcairn, his friend and former parishioner. Together with other enthusiastic New Church devotees, they envisioned the Academy of the New Church. This Academy was to be a place where all studies could be undertaken in the light of New Church theology.

Figure 8: Selections from an 1880 brochure advertising the Academy of the New Church. Courtesy of the Worthington Library Unofficial New Church Archive at Peeble Hall.

Figure 9: The original constitution of the Philadelphia Society of the New Jerusalem at Cherry Street, 1856. Academy of the New Church Archives.

As seen in the brochure reproduced above (Figure 8), the Academy sought to be an all-encompassing institute of learning. Benade and his congregation had such focused devotion to the New Church worldview that, in their eyes, no secular scholarship was deep enough to feed both the intellect and the spirit. Once Benade professed that even science texts were lacking, as they did not take the Divine into account. (5)

New Church worship was essential to the life of the Academy. At that time, only those who were sympathetic to its teachings were welcomed as students. But that is not to say that the early days were unfriendly and insular. In fact, the “world tour” during which Benade and Pitcairn acquired the beginnings of the museum was undertaken to help spread the ideas of the New Church around the world. When he returned, Benade hosted lectures using museum objects in one of the Academy’s schoolrooms. From the very beginning, the museum was finding its mission.

Figure 10: Benade’s personal copy of The East: Sketches of Travel in Egypt and the Holy Land, 1850, acquired 1861. Courtesy of the Worthington Library Unofficial New Church Archive at Peeble Hall.

The original marble baptismal font from the Cherry Street Temple is in the collection of Glencairn Museum (Figure 11). As in all Christian churches, baptism is an important practice in the New Church, which teaches that this sacrament “is a symbol of spiritual rebirth, and thus of introduction into the church, which is effected by introduction into good by means of truths from the Word.” (6) New members of the church would come before the baptismal font and receive the sacrament of baptism, administered by a priest. Both adults and children were welcome, and on at least one occasion an entire family of four made the commitment to the New Church through the ritual waters in this font. (7)

Figure 11: Left: Marble baptismal font from the Cherry Street Temple, in the collection of Glencairn Museum. Here it is pictured in the family chapel at Glencairn, where it is occasionally still used by New Church members for infant baptisms. Top right: Liturgy for the New Church, 1880, personal copy of Rev. Richard de Charms, headmaster of the Boys’ School at Cherry Street. Bottom right: Selection from the baptism ritual from the 1880 Liturgy. Courtesy of the Worthington Library Unofficial New Church Archive at Peeble Hall.

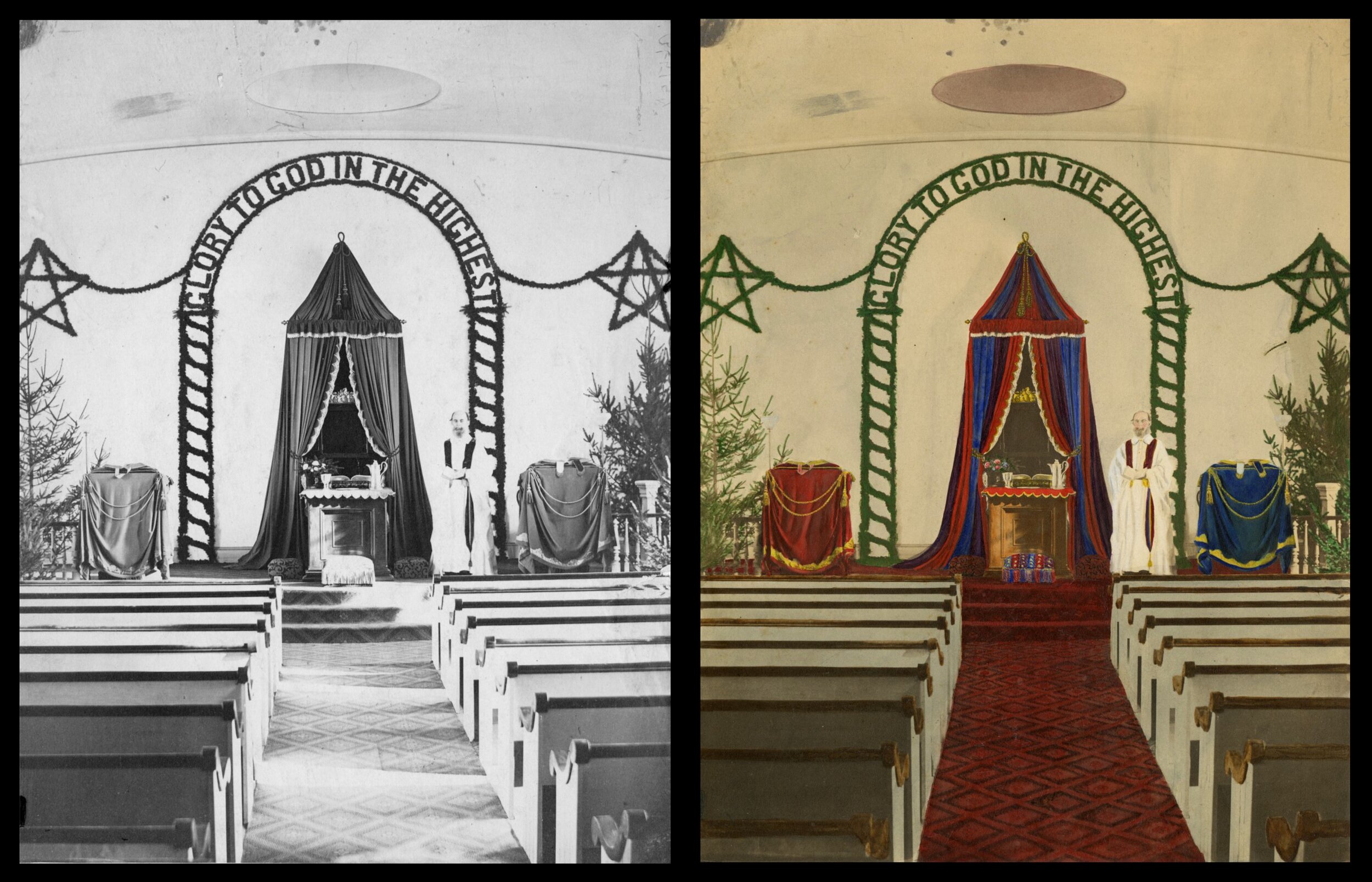

Figure 12: Two contemporaneous images of Rev. William H. Benade on the Cherry Street chancel before 1874, decorated for Christmas. (8) Note the shift in location of the baptismal font from the earlier photo in Figure 6. Academy of the New Church Archives.

In Figure 12 we see two similar images side-by-side. On the left is the original Christmas photo taken sometime before 1874, and on the right the hand-colored photo made at the same time. At the far right of the picture is the baptismal font, and standing by the altar is Rev. William Henry Benade. These photos, preserved in the Academy of the New Church Archives, are a significant treasure for our understanding of the journeys of these artifacts. An early description of the Temple reveals that the intended place for the baptismal font is in the common area of the sanctuary, rather than on the chancel, which was the domain of the priests. There was no baptismal font at the time of the building’s dedication, though its place was pre-determined: “on the floor to the south, outside the platform, is to be placed the baptismal font.” (9) This description matches its placement in Figure 6, but not in Figure 12. It might be the case that the decorators moved the font to make room for the Christmas trees; a close examination of the image shows two trees on either side of the lectern and pulpit, both on the chancel platform and on the congregation floor. Years later, Christmas in the Society would look very different, not only because the Society had removed to a new location spanning Wallace and North streets in Philadelphia, but because in 1888, Benade oversaw the replacement of Christmas trees with something he considered to be more relevant to the holiday. A report from one who was there reads:

“So, on Christmas Eve, instead of the usual tree, the spaces on each side of the platform in the Hall were occupied by wide tables on which were arranged representations, taken from the literal sense of the Word, of scenes at the birth of our LORD. On the left was a landscape where were flocks of sheep whose attendant shepherds, in attitudes expressive of awe and astonishment, gazed at the angel who announced the glad tidings of the babe in the manger. On the right-hand side was a representation of an Oriental horse-stable, showing better than any description in words how humble and mean and wretched was the birthplace of the LORD. Palms and plants, such as might grow in Palestine, surrounded these tables without intercepting the view, while the walls around were decorated with inscriptions. Over the repository was one taken from the Doctrines, and one on each side from the letter of the Word. There were others also in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin.” (10)

Figure 13: Mildred Pitcairn at Glencairn with her grandchildren in 1967, in front of a Nativity scene made for the Pitcairn family in the 1920s by Winfred S. Hyatt. Bryn Athyn Historic District Archives.

This tradition of Christmas story “representations” is one that was important to the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn family when they resided at Glencairn (Figure 13), and has continued to be meaningful for members of the New Church today. Glencairn’s annual World Nativities exhibition showcases representations of the Christmas story from around the world; it can be seen during each Christmas season. (11)

In 1888, museum artifacts became part of the life of worship at the Cherry Street Temple. The same reporter as above mentions that on Christmas Eve, “water-bags and other articles used by the inhabitants of that country were hung about the Hall.” (12) These artifacts are likely from among those treasures Benade and Pitcairn brought home from their 1877-1879 world tour. The founders made regular use of museum artifacts to bring lessons alive, and seemed to seldom let teachable moments pass them by.

Education was a main feature of the Cherry Street Temple. The program at Cherry Street was initially for the training of priests for the New Church ministry; however, it was soon determined that more extensive training was required. The Academy expanded to eventually include a boys school, a girls school, a college, and a theological school, all of which existed with the church and treated the Cherry Street location as their hub. While there are books preserved within the Academy’s library that were part of the educational life of the early Academy, only two instructional tools are known to have survived from the daily instruction of the younger members of the student body: an 1856 child’s primer containing the alphabet and stories, and a slate for writing (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Left: Two slates, one of which is known to have been used at Cherry Street. Center: Children’s primer used at Cherry Street. Right: Top portion of a pulpit known to be used at Cherry Street. All in the collection of Glencairn Museum.

The effective education and careful upbringing of children was a priority for Benade. His philosophy of teaching led him to be an engaging instructor, teaching through stories and topics of interest to young people. He was remembered by one former pupil for his skill at drawing, and how he would regularly capture students’ attention with illustrations he would draw (13)—a skill that ran in the family, as seen in the preserved works of his brother James Arthur Benade (1823-1853). Rev. Benade’s appreciation for children shines through in his writing on educational philosophy, some of which is still studied at Academy schools today.

Figure 15: A computer rendering of the classroom on the first floor of the Cherry Street building. There is no known photograph of this space. The structure is rendered based on insurance drafts, and the setup is based on sketches of Benade’s previous schoolroom, which was located on 10th Street, just south of Market Street. The furniture is modeled based on photographs at the Academy’s later location on Wallace Street, preserved at the Academy of the New Church Archives. Step into the classroom for the first time in 133 years by clicking on the photo above or here. (Computer rendering by Joel Christian Glenn.)

A feature missing from the photos reproduced in Figure 12, perhaps having been displaced by Christmas décor, is the chairs on either side of the altar in the center of the chancel. These two chairs are preserved in the New Church collection at Glencairn (Figures 16, 17). They are carved with partially inlaid wood, and have velvet cushions that have faded from their original color. Museum records indicate that they were in use at Cherry Street as early as 1876, the year before the establishment of the Academy. They continued to be used, though not on the chancel, after the church moved three-quarters of a mile away to North Street. These chairs were an important practical feature of worship life, as one priest could be seated while another priest is participating in the service, or if an interlude is offered by the choir.

Figure 16: Chairs from the chancel of the Cherry Street Temple, now in the collection of Glencairn Museum.

Figure 17: An arrow points to a chair in the library at the Academy’s location on Wallace Street, originally situated on the chancel at Cherry Street. Academy of the New Church Archives.

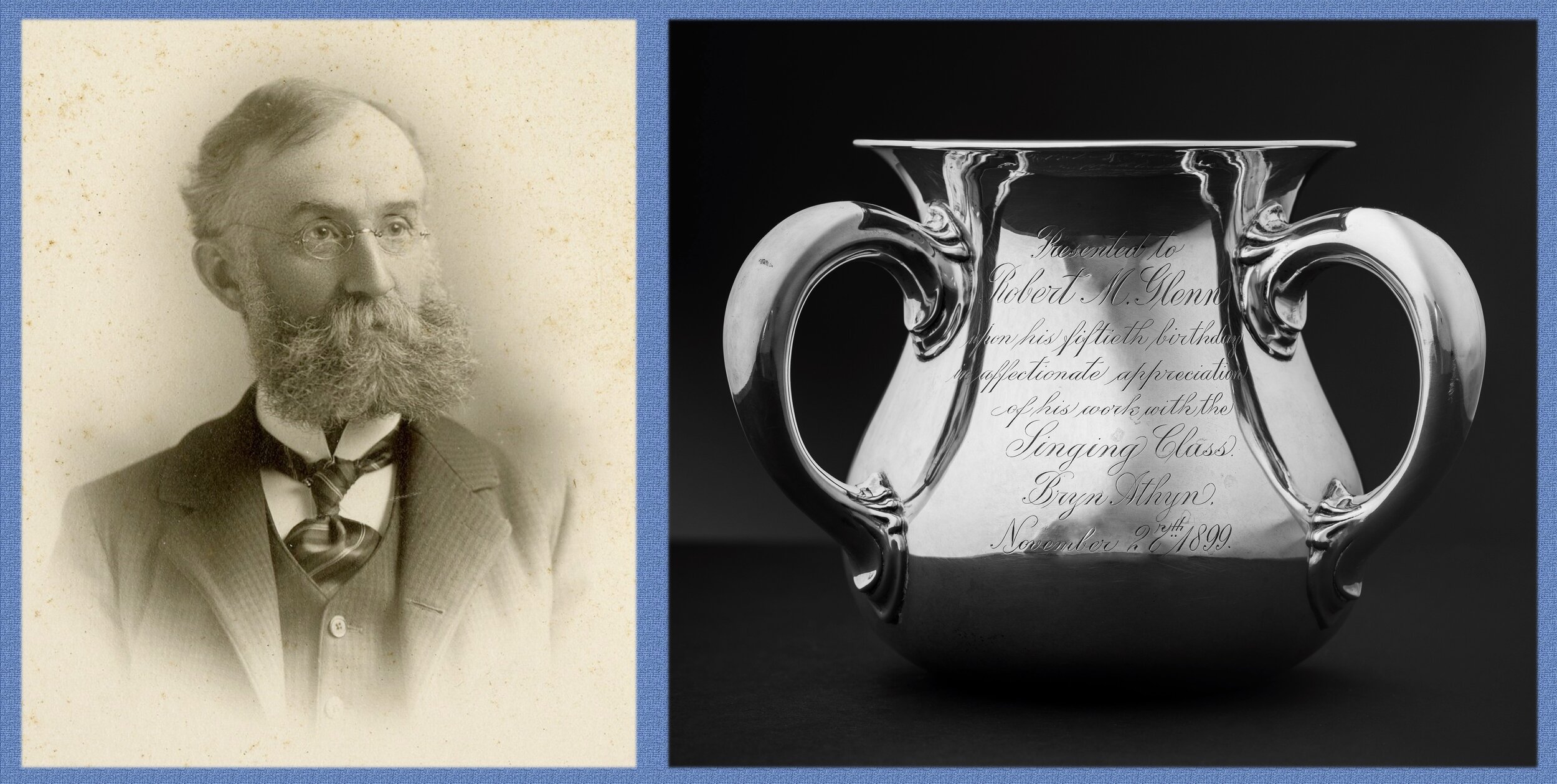

The choir at the Cherry Street Temple (Figure 18) was conducted by Robert Morris Glenn, whose daughter, Mildred, would later marry Raymond Pitcairn in Bryn Athyn on December 29, 1910. Reports indicate that music was a regular feature of worship at Cherry Street. One visitor rudely remarked in a Sunday paper that “a good sneeze would drown the choir!” (14), though the consensus of the Society seems to have been one of appreciation. Glenn, whose “love for music was, indeed, one of his most marked characteristics,” (15) was honored on his fiftieth birthday with a silver loving cup (Figure 19) recognizing his contributions to the musical life of the church. Glenn’s father, Benjamin Fisher Glenn, had overseen the construction of the Cherry Street Temple.

Figure 18: Choir stalls at the west end of the Cherry Street building in 1880. Staircases to the entrance and classroom below were on either side of the room.

Figure 19: Robert Morris Glenn in 1902, and the three-handled loving cup gifted to him on his fiftieth birthday. The cup reads, “Presented to Robert M. Glenn upon his fiftieth birthday in affectionate appreciation of his work with the Singing Class. Bryn Athyn, November 27th 1899.” From the private collection of the Glenn descendants. Photo credit: Cole Lambertus Photo.

The origin of the chairs on the chancel is unknown; however, Academy records have preserved a receipt for the corresponding pulpit and lectern (Figure 20). The pulpit and lectern were purchased in December, 1874, from R. N. Buckley, who made “Cabinet ware of every description” at his steam mill at 23rd and Chestnut Streets, including “every description of interior church work: pews, pulpits, reading desks, etc.” (16) The locations of the lectern and pulpit are not known today.

Figure 20: Receipt dated December 31, 1874 for the ash lectern and pulpit for the Cherry Street Temple. Issued by R. N. Buckley of the Chestnut Street Steam Mills. Academy of the New Church Archives.

The central feature of the Cherry Street chancel has been preserved, and is serving the same purpose today that it served at Cherry Street. At the center of Figure 6 stands the most important feature of the church—the open Word, or Sacred Scripture. Photographs show this altar installed at Cherry Street as early as 1880. The faith of the New Church holds that it is through the Sacred Scripture that people become connected with God and learn their purpose and potential in life. Not only this, but it is the Word of God that builds a bridge between this natural world and the next spiritual world. This was a belief of great importance at the Cherry Street Temple, and for that reason the centerpiece of the church is the altar holding the Word. This belief was represented in the worship rituals of the Cherry Street Temple, described in this report from 1884:

“In worship the priest of the New Church must have his thought and affection directed to the LORD. The LORD being the Word, his foremost external thought is directed toward the Sacred Scriptures. Hence, when he begins worship, he, in the thought that all the good and truth of the worship must come from the LORD, reverently takes the Word out of the sacrarium, and, placing it upon the altar, opens it, for the Word is an open book, and not a closed one, in the New Church. The people, in the humble acknowledgment of the Infinite Mercy of the LORD, arise at the appearance of the LORD as the Word.” (17)

The “sacrarium” was a recession in the wall of the sanctuary, about two feet deep. (18) This space can be seen in some renderings of the building in contemporary atlases (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Two atlases showing the sacrarium. This was not an original feature of the building, and seems to have been added sometime after 1874.

Figure 22: Left: Portrait of William Henry Benade in 1892 wearing vestments indicative of the Chancellorship of the Academy of the New Church; medallion of the Academy (present location unknown); and his purple silk cape. Right: Two Chancellor’s capes preserved in the collection at Glencairn Museum. Today the Chancellor of the Academy still wears a crimson robe to signify his office (pictured). Photo courtesy of Rebekah Russell.

At the dedication of this church in 1857, a copy of the Sacred Scripture was carried into the sanctuary for the first time by Rev. Benade, who entered the room wearing white priestly vestments “over which was fastened a purple silk cape” (Figure 22). (19) He placed the book on the altar for the first time, knelt, and prayed. At the end of services, the book was placed back in the sacrarium. In order to accommodate for this ritual, the altar sat a few feet in front of the sacrarium with enough room for the priest to maneuver.

In 1888, the New Church congregation, having procured a more commodious property further north, sold the building to St. Clement’s Episcopal Church less than a block away. The Temple was converted to a successful charitable hospital operation, and most traces and memory of its ever having been a school or house of worship were eliminated in the process. The Cherry Street Temple lost its arched roof, and gained one and a half stories for the use of the new hospital (Figure 23).

Figure 23: The former Cherry Street Temple, now St. Clement’s Hospital, depicted in 1889 (St. Clement’s Magazine, October, 1889). Special thanks and gratitude to Andrew Nardone, Parish Administrator and Sacristan of St. Clement’s Church, for sharing his extensive knowledge of the history of St. Clement’s and the neighborhood, and for finding these images of the Cherry Street Temple transformed.

The altar traveled with the Society and eventually found itself situated at the highest place of honor in the majestic Bryn Athyn Cathedral. Much like the Temple, the altar went through its own modifications. To look at it today is to see the same form and function but not entirely the same presentation. (20) Originally made merely of dark mahogany, the altar was apparently leafed with gold, and ornamented in preparation for its placement in the Cathedral. In early plans for the Cathedral, a large repository for the Word was in the center of the chancel. However, the final design was of a simple altar on which the Word would remain at all times, surrounded by seven lampstands evoking imagery from the Book of Revelation (Figure 24).

Figure 24: Right: The Cherry Street altar situated in Bryn Athyn Cathedral, where it remained from the Cathedral’s dedication in 1919 until it was replaced in 1995 (My Story of the Bryn Athyn Cathedral, R. Lindquist, 2004). Left: A model of an early plan for the same space that never came to fruition. Bryn Athyn Historic District Archives.

In 1950, 94 years after the dedication of the cornerstone of the Cherry Street building, Raymond Pitcairn reflected on this important link to the past:

“The traditional symbol of the Lord used in churches, temples, and homes of the Academy and the General Church is the open Word in the form of a bound copy of the Old and New Testaments, placed in a repository or on an altar . . . In the Cathedral . . . we use the old Academy Cherry Street altar,—overlaid with gold,—on which rests a bound copy of the Old and New Testaments. The Cherry Street altar was also used for Society and school Worship after the Academy Schools moved from Cherry Street to North and Wallace Streets in Philadelphia.” (21)

Using the Cherry Street altar in Bryn Athyn Cathedral served as a bridge between old and new, keeping memories of the past alive for the remainder of their lifetimes. It is worth noting that for his entire life, from his earliest childhood in Philadelphia to the end of his life in Bryn Athyn, Raymond Pitcairn worshipped before this altar (Figure 25).

Figure 25: A visual timeline of the various homes of the altar, which has served as a centerpiece of New Church worship since its time at Cherry Street beginning in 1856.

The main sanctuary of Bryn Athyn Cathedral, however, is not the current home of the altar formerly at Cherry Street. In 1995, under the direction of Lachlan Pitcairn (1922-2013), Raymond’s son, the altar was removed to make way for a new altar that he commissioned. After spending nearly a decade in storage, the altar was put to use in the council chamber of the Cathedral, where currently the children’s service is held. (22) Though it is not the same place of honor that it once held at Cherry Street, North Street, or in the chancel at the Cathedral, there is something poetic about this artifact’s present location. It is situated beneath a stone corbel in the likeness of William Henry Benade, who himself once preached before it, looking down from the eaves on worshipping children—the future of the church and the continuing legacy of the Academy that he started (Figure 26).

Figure 26: Left: Detail of Cherry Street chancel from Figure 12. Middle: Rev. William Henry Benade, seated, visits the playschool in Huntingdon Valley, PA, in 1891. Academy of the New Church Archives. Right: Altar beneath sculpted corbel head of Benade in the council chamber at Bryn Athyn Cathedral in 2021.

Figure 27: The Reverends Joel Christian Glenn (right) and Christopher Augustus Barber, pictured here after a game of badminton in 2014. (Joel won.)

The Reverends Christopher Augustus Barber and Joel Christian Glenn (Figure 27) have been friends since they first they met at Bryn Athyn College. Today they are both ordained priests in the General Church of the New Jerusalem, an international church with headquarters in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. They report that they are glad to have had the opportunity to collaborate on another article for Glencairn Museum News (see also Glencairn’s 1796 Halfpenny Token: A 3D Video Rendering of the Earliest New Church Temple). Though they are a world apart, with Joel serving as the assistant pastor of the New Church in Westville, South Africa, and Chris as a teacher of religion at the Academy of the New Church in Bryn Athyn, they enjoy the opportunity to work together on projects related to New Church history and say they are grateful to Glencairn Museum for supporting their scholarship.

Endnotes

1. You can read more about this exciting journey and this photograph in “The Purchase of the Lanzone Egyptian Collection (1878),” a 2015 article in Glencairn Museum News by Ed Gyllenhaal.

2. Benade, W. H. (1856, September 11). “Laying of the corner-stone of School-House – Cherry St. above 20th.” Academy of the New Church Archives.

3. Bachmann, John - Artist. Bird's Eye View of Philadelphia. 1857. Paintings. Free Library of Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/53327.

4. For a more in-depth review of this history, see Hidden City Philadelphia’s article, “Medieval Masterpieces Inspired by Swedish Mystic Still Dazzle in Montco” by Sam Newhouse.

5. Block, Marguerite Beck, 1984. The New Church in the New World. New York: Swedenborg Publishing Association.

6. Swedenborg, Emanuel, Secrets of Heaven, passage 9032.

7. New Church Life, May, 1881.

8. This photograph is erroneously labeled 1880. However, the physical construction of the room, the pulpit and lectern, as well as Benade’s younger appearance, demand an earlier date.

9. New Jerusalem Messenger, 1857.

10. New Church Life, January, 1889.

11. To read more about this tradition, especially as it overlapped with Benade’s pre-New Church ministry and roots, see “Moravian Nativity Scene Exhibited at Glencairn,” Glencairn Museum News No. 1, 2011.

12. New Church Life, January, 1889.

13. “Mr. Benade’s First New Church School,” New Church Life, 1909.

14. New Church Life, 1881.

15. “A Life Sketch,” New Church Life, 1902.

16. The New Orleans Christian Advocate, December 2, 1875, p. 6.

17. “External Representatives,” New Church Life, 1884.

18. New Jerusalem Magazine, September, 1857, p. 407.

19. New Jerusalem Magazine, September, 1856, p. 408.

20. Many thanks to Peter Boericke and Gannon Blair for their insights into the later decoration of this altar.

21. Pitcairn, R., “Benade Hall Chapel and Chancel.” Academy Journal of Education, March, 1951.

22. Thanks to Jim Adams and Franklin Vagnone, former directors of the Cathedral, for information on the altar’s life in recent decades.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.