Glencairn Museum News | Number 9, 2022

The stela of Maienhekau in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266). This “door” was a portal for the ka, or “life force,” of the tomb owner.

Figure 1: Stela of Maienhekau (Louvre C59). Image courtesy of the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

A funerary stela in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266) commemorates an official named Maienhekau (see photo above). He served during the reign of Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BCE), the famous military ruler of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. From at least as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3200 BCE), funerary stelae were an essential part of ancient Egyptian funerary preparations. These stelae were typically carved out of stone, although wooden examples are also known. They were displayed in an upright position, either freestanding on a base, or engaged in a wall of a tomb or memorial chapel. The reign of Tuthmosis III was marked by the expansion of Egypt’s control in the Near East and in Nubia. Although Maienhekau was not a prominent official, he is known from several funerary monuments that have his name and the names of his family members. The name Maienhekau means “lion of the rulers,” and this individual seems to be the only known holder of that personal name (Figure 19). (This stela was briefly discussed in “Preparations for a Good Burial: Funerary Art in Glencairn’s Ancient Egyptian Gallery” (Glencairn Museum News, No. 5, 2019.)

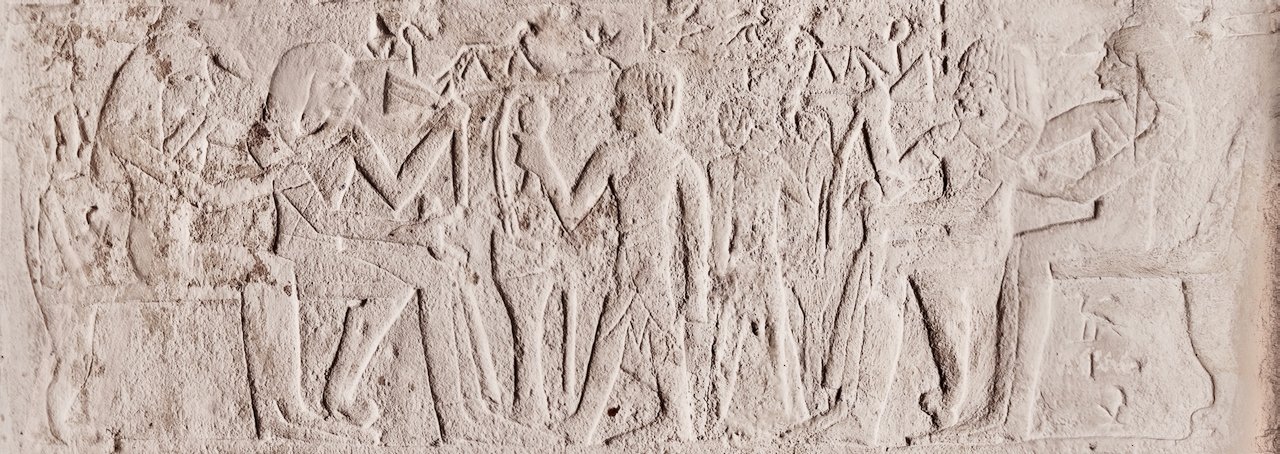

One of Maienhekau’s funerary monuments is now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Figure 1). This round-topped polychrome limestone stela was probably originally set up at the site of Abydos (see map, Figure 10). Abydos was a religious center where important sacred festivals took place. Abydos was also a location intricately connected to the god Osiris, the king of the dead. The Egyptians believed that Osiris was buried at this site, and they would go on pilgrimage trips so they could see or take part in the annual Osiris festival. Many ancient Egyptians constructed their tombs at this site so they could be close to this god and his celebrations. Some people also built cenotaphs (or “false tombs”) where they could be commemorated at Abydos even if they were buried elsewhere in Egypt. Maienhekau’s stela in the Louvre likely came from one of these cenotaphs or small memorial chapels at Abydos.

The decoration on the Louvre stela is divided into three sections. At the top, Maienhekau is shown together with his son, Nehemmeshaef. On the left side, Maienhekau stands in a worshipful position with his arms raised before a seated image of the god Osiris (Figure 2). An offering table is set up before the god holding various foodstuffs. On the right, Maienhekau stands in a similar pose before the god Ptah (Figure 3). An offering stand is set up before the god and a single lotus blossom is placed on top. Nehemmeshaef stands behind his father, facing the god Ptah, holding a bird in one hand and a folded cloth in the other hand. Eleven short columns of hieroglyphs appear above this scene, identifying the figures below. Osiris is called the “Foremost of the Westerners,” while Ptah is identified as “the one who is south of his wall, the Lord of Ankhtawy.” Both descriptions are typical epithets (or descriptors) of these deities. Maienhekau’s title is listed as “standard bearer.” His son’s title is not recorded.

Figure 2: Bronze statuette of the god Osiris in the Glencairn Museum collection (E74). Osiris was the husband of Isis and the father of Horus.

Figure 3: Statuette of the god Ptah in the Glencairn Museum collection (E999). Ptah was the chief deity of the city of Memphis. He was a creator god and the patron of craftsmen.

The second register has a scene of two people seated before an offering table. A small female figure stands behind the woman’s chair, and three female figures face the seated couple. Hieroglyphs above the figures give their identifications. The standard bearer Maienhekau sits with his wife, the lady of the house, Henuttawy. The small figure behind her is called “Her daughter, Tanetabu.” The three women standing before the couple are identified as daughters. From left to right we have: Taryry, followed by Tanetabu, and then Tamyt, who is called “true of voice before Osiris.” This statement following her name may show that she had passed away earlier. The daughter closest to the seated pair holds a libation vessel and pours water for her parents. She holds a folded cloth in her other hand. The other two women each hold a lotus flower in one hand and a folded cloth in the other. One flower is just a bud, while the other has fully bloomed. It should be noted that the lotus flower (or water lily) had symbolic meaning for the ancient Egyptians. This fragrant water plant bloomed in the morning and closed in the evening. This cycle recalled the daily appearance of the sun god at dawn each day and his return to the underworld at nightfall. Because of this, the lotus also symbolized rebirth and regeneration.

The third register, at the bottom of the stela, has three lines of a hetep-di-nsw offering prayer. Reading from right to left, the text says: “An offering which the king gives to Osiris, ruler of eternity, the great god, Lord of Abydos, and Anubis, foremost of the divine booth who is in his wrappings, Lord of the sacred land, and Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. May they give invocation offerings of bread, beer, cattle and fowl, every good and pure thing and cloth for the ka of the commander (of the ship) ‘Victory in Thebes,’ Maienhekau, fathered by the dignitary Min and born of the Lady of the House [name blank].” (Just like modern boats, ancient Egyptian watercraft had names: see Figure 4.)

We learn several things about Maienhekau from this stela. We learn which titles he held. We learn that his father’s name was Min, and that this man did not seem to hold any important positions. We see that Maienhekau had a wife named Henuttawy, and they seem to have had a son named Nehemmeshaef and daughters named Tanetabu, Taryry, and Tamyt.

Another stela with Maienhekau’s name is in the Egyptian Museum in Turin (Figure 5). Like the Louvre stela, this monument is carved from limestone and is painted. It is round-topped and likely also came from Maienhekau’s memorial chapel at Abydos. Interestingly, the Turin stela seems to have originally been made for someone else; Maienhekau usurped it and had it re-carved with his own name and the names of his family members.

Figure 4: Above: Just as modern boats and ships have names, so, too, did ancient Egyptian watercraft. From the monuments of Maienhekau we learn the names of several ships associated with New Kingdom royalty. Image of the Canard courtesy of Peter J. Wegner. Below: Painting of a boat from the New Kingdom tomb of Menna.

Figure 5: Stela of Maienhekau (Turin 155). Image courtesy of the Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

This stela is divided into four sections. At the top, a male figure offers a libation before three deities. At the far left, a falcon-headed Horus stands behind a seated figure of Osiris. They are shown within a type of shrine. A seated figure of the god Ptah (now damaged) is in front of them. Traces of offering stands can be seen between Ptah and the figure of Maienhekau. Above this scene are a pair of recumbent jackals facing a pair of wedjat eyes that rest above three nefer hieroglyphs reading “beauties.” A hieroglyphic label names each figure in the scene. Horus is called, “Horus, protector of his father, son of Isis gentle with love, the great god who resides in Ta-wer”; Osiris is the “Foremost of the Westerners”; and Ptah is called “Lord of the sky.” Maienhekau is identified as “the standard bearer (of the unit/ship) ‘Victory (in) Thebes.’” (See Figure 6.) When Maienhekau had this stela re-carved, he added the figure of Ptah and removed a figure originally in front of the standing male figure seen in the top register on the right.

Figure 6: These hieroglyphs are the word for “standard bearer.” This title appears several times on the monuments of Maienhekau.

In the second register, two standing male figures offer libations to two seated couples. Short columns of hieroglyphic text identify the figures in the scene. On the left, the “lady of the house, his beloved, Henuttawy, true of voice” sits next to Maienhekau, who is “noble before Osiris.” An offering stand with a single lotus appears between the couple and the libating figure, who wears the leopard garment of a sem-priest (Figure 7). Above him, the text reads, “Making hetep-di-nsw offerings by your son, your beloved, Nehemmeshaef.” A second couple sits on the right side. Here, Maienhekau is called the “standard bearer [of the ship . . .] ‘The young bull.’” He is again paired with his wife, Henuttawy, who is called the “lady of the house.” The standing figure making offerings to them is dressed differently from Nehemmeshaef. This man wears a short kilt and holds a water jar in one hand and grasps a duck in his other hand. The text above him says, “Making hetep-di-nsw offerings by your son, his [sic] beloved, Mehu.”

Figure 7: Sem-priests wore a distinctive leopard skin garment. Here we can see three examples of such a garment. The first is an actual garment made of painted linen. The statue depicts a man named Anen who was a sem-priest during the reign of Amenhtoep III. The final image is from the tomb of Tutankhamun and shows the pharaoh Ay dressed in the leopard stole while carrying out funerary rites for the deceased boy king.

The third register shows a seated couple on the left in front of a table with offerings. A standing male figure gestures towards them while three seated female figures appear behind him on the right. The figures are identified with hieroglyphic labels. The seated man is “his father, Min” and the woman is the “lady of the house, Ryry, his mother.” Min holds a lotus blossom to his nose. The standing man is identified as “his son, Khaemwaset.” The seated female figures are (from left to right): Taryry, “his daughter,” Ta(net)abu, and “his daughter” Takhat. Each woman holds a lotus flower in their hands.

Figure 8: This cartouche reads “Menkheperre,” the throne name of King Tuthmosis III.

The bottom section of the stela consists of a funerary prayer. Written in five lines and reading from right to left, it says: “An offering which the king gives to Osiris, foremost of the westerners, the great god, ruler of eternity, king of the gods (to) Ptah, the noble one, father (of the gods), lord of Maat, foremost of the Ennead, Amun-Re, bull of his mother, so that they may give the invocation offerings of bread, beer, cattle, fowl, cloth, incense, ointment, fresh water, wine, milk, all things good and pure, all things pleasant and sweet, to breathe the sweet breath of the north wind, to drink at the creek of the river and a beautiful burial after the mooring in the west for the ka of the bearer of arms of Menkheperre, commander (of the ship) ‘Victory in Thebes,’ commander of the ship ‘The Bellicose Cow,’ Standard bearer of (the ship) ‘Amenhotep the Bull Calf,’ Maienhekau.” (Menkheperre is the throne name of King Tuthmosis III; see Figure 8.) A kneeling figure with his arms raised in prayer appears at the bottom left of this inscription.

From this Turin stela, we learn a little bit more about Maienhekau. We see that his wife, Henuttawy, is mentioned again. His father’s name, Min, appears, as does the name of his mother, Ryry—information that was missing on the Louvre stela. Maienhekau’s son, Nehemmeshaef, appears here, as he did on the Louvre stela, but now he is joined by his brother, Mehu, another son of Maienhekau. Two daughters who appeared on the Louvre stela, Taryry and Tanetabu, are also on the Turin stela, and they are joined by another sister who is not mentioned on the Louvre stela, Takhat. A man who is not on the Louvre stela appears here before Maienhekau’s parents. He is called “his son,” so perhaps this man, Khaemwaset, is a brother of Maienhekau. We also learn more about the positions that Maienhekau held. On this stela, he has several different titles, including: “the standard bearer (of the unit/ship) ‘Victory (in) Thebes,’” the “standard bearer [of the ship . . .] ‘The young bull,’” “the bearer of arms of Menkheperre,” the “commander (of the ship) ‘Victory in Thebes,’” the “commander of the ship ‘The Bellicose Cow,’” and the “standard bearer of (the ship) ‘Amenhotep the Bull Calf,’ Maienhekau.”

The location of Maienhekau’s tomb is currently unknown, but another group of objects bearing his name gives us a hint as to where the tomb was originally found. There are a few funerary cones that are decorated with the name and title of this individual. This type of artifact is typically found in the area of Thebes in southern Egypt (see map, Figure 10). Funerary cones decorated the façade of certain New Kingdom Theban tombs; the pointed end was inserted into the wall face, and the round, flat end displayed the name and titles of the tomb owner (Figure 9). One of Maienhekau’s funerary cones was found in the city of Thebes at the site of Dra Abu Naga, close to the tomb of a man named Hery (Tomb 12). Another fragmentary example of one of his cones (now lost) was also found in this area. This suggests that Maienhekau’s tomb was located at or near Dra abu el Naga, a cemetery site that contains many tombs of officials from the New Kingdom (Figure 11).

Figure 9: An example of a ceramic funerary cone similar to those of Maienhekau. The line drawing shows the decoration on Maienhekau’s cones. The inscription reads, “the standard bearer, Maienhekau.”

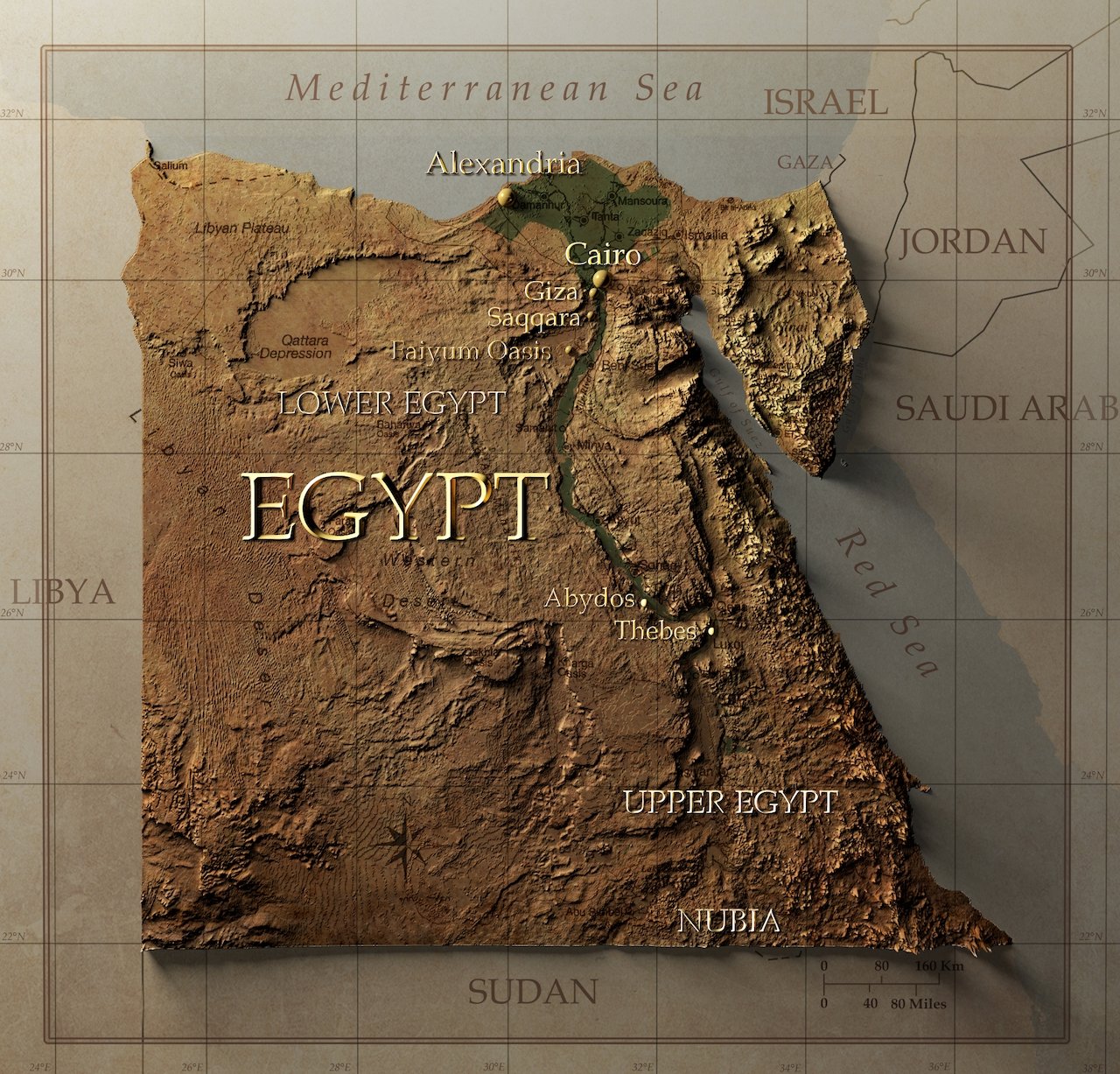

Figure 10: The locations of Abydos and Thebes, the probable original locations of Maienhekau’s stelae, can be seen on this map.

Figure 11: This sketch shows what a typical Theban tomb of the 18th Dynasty would look like. The tomb is cut into the rock and has a small courtyard. Funerary cones decorate the upper part of the façade (indicated here by the black dots).

Another important monument belonging to Maienhekau is in the Glencairn Museum collection. (See lead photo and Figure 12.) In 1963, this rectangular limestone funerary stela was in the possession of a French antiquities dealer named Guy Montbaron. After that, it was offered for sale at various auctions until it was purchased from Sotheby’s in 1985 and accessioned into the Glencairn collection. The provenience of the stela is unknown, but it probably came from Maienhekau’s Theban tomb together with the funerary cones that bear his name.

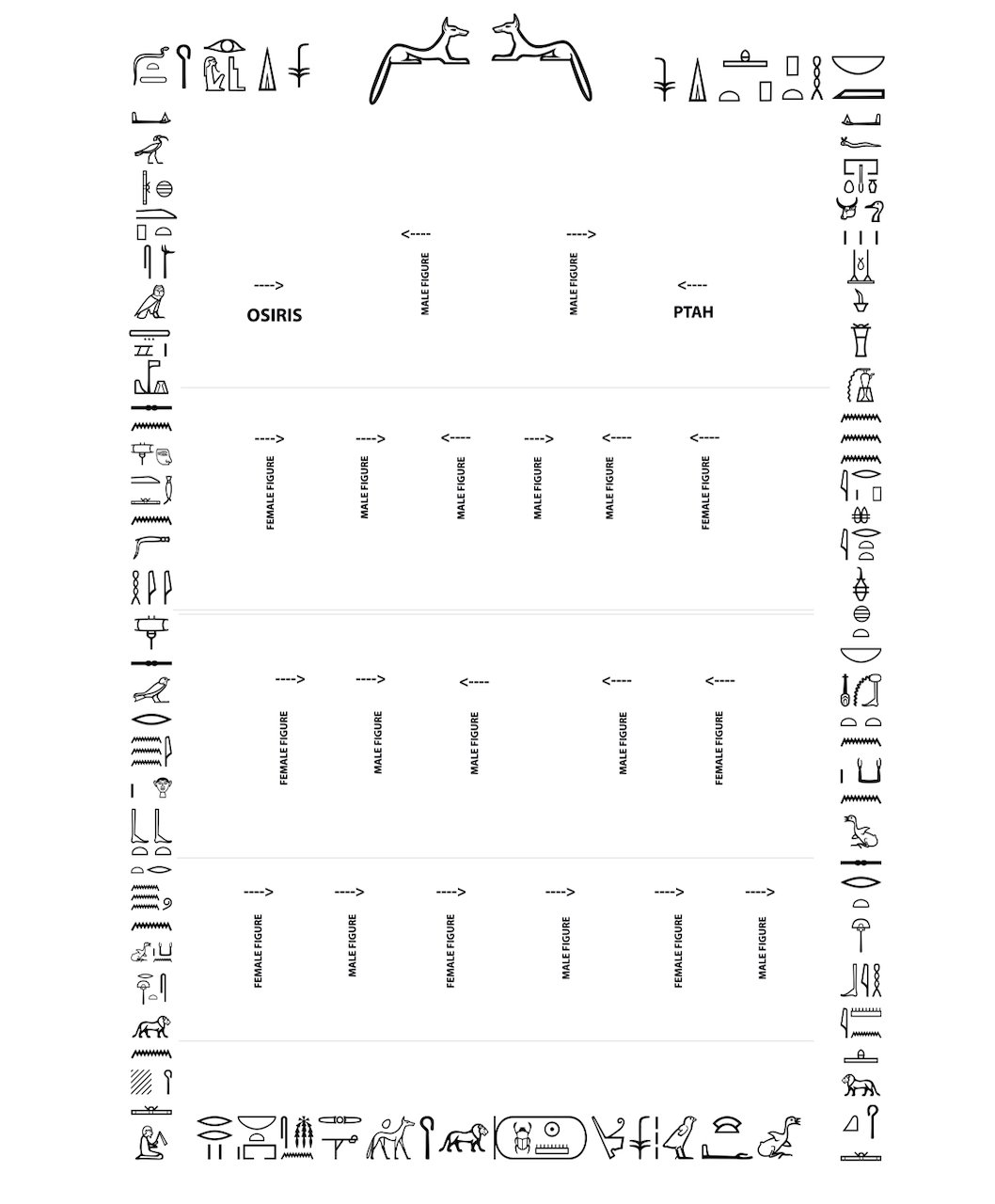

Figure 12: A diagram of the hieroglyphic inscriptions and decoration on the stela of Maienhekau in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266).

Glencairn’s Maienhekau stela is of a type known as a “false door” stela. Stelae of this kind are a development from the architectural feature of the same name that was common in Old Kingdom tombs (Figure 13). This “door” was conceived of as a portal for the ka, or “life force,” of the deceased. The ka could magically pass through this doorway and partake of the offerings left for it. False doors were typically placed in above-ground tomb chapels near offering tables where food and drink would be left for the deceased. False-door stelae first appeared in the Middle Kingdom and remained popular during the New Kingdom.

Figure 13: The False door of Iryptah (E14318). This false door dates to the Old Kingdom and comes from the site of Saqqara. Image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

The stela has an inscribed “frame” with two offering prayers that mirror each other. At the center of the frame at the top are two recumbent jackals. The prayer on the left-hand side reads from right to left and then down the side of the stela, while the text on the right-hand side reads from left to right and then down. These funerary prayers are hetep di nsw invocations like those seen on Maienhekau’s other two stelae. The texts invoke funerary deities and request offerings for the deceased. Maienhekau is named and his titles are given.

On the left side, the text reads: “An offering which the king gives to Osiris, ruler of eternity to give effectiveness in the sky, power on earth, (triumph) in the underworld, to breathe the sweet breath of the northern wind, to drink at the creek of the river for the ka of the standard bearer, Maienhekau.” On the right side, the text says, “An offering which the king gives to Ptah [Lord of Maat] so that he will give invocation offerings of bread, beer, cattle, fowl, cloth, incense, ointment, fresh water, wine, milk and every good and pure thing for the ka of the standard bearer (of the ship) ‘The young bull of Amenhotep,’ Maienhekau.”

A single line of text appears on the inner bottom lip of the stela. It reads, “the arms bearer of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkheperre, Maienhekau, the son of the dignitary Min, born of the lady of the house, Ryry.” This text tells us that Maienhekau served during the reign of the pharaoh Tuthmosis III whose prenomen, or throne name, was Menkheperre.

The decoration of the inner part of the stela is divided into four registers. In the uppermost register (Figure 14), two representations of Maienhekau kneel in adoration before Osiris and Ptah. One the left-hand side, Osiris is seated on a throne. He is mummiform, wears the white crown, and holds a was-scepter in his hands. He is identified as “Osiris, foremost of the west.” The label above the kneeling figure reads, “(Adoration) by the standard bearer [of the ship] ‘The Bellicose Cow,’ Maienhekau.” On the right, a similar figure kneels in front of the god Ptah, who is seated on a block-shaped throne. Like Osiris, Ptah holds a was-scepter and is shown mummiform. He wears his characteristic skullcap head covering.

Figure 14: Detail of the first register of the stela of Maienhekau.

A scene of two seated couples with a standing male figure in front of each pair makes up the second register (Figure 15). On the left we see Maienhekau seated and holding a lotus blossom. Next to him is a woman with a long, full wig topped by a lotus bud. A label behind her gives her name, Meryt, but offers no sign of her relationship to Maienhekau. The man standing before this pair offers them a libation. He is identified as Nehemmesha(ef). On the right side, Maienhekau sits with Henuttawy, the woman who is elsewhere called “his wife.” She wears a full wig with a lotus blossom atop her head. He holds a lotus flower in his hand. They are being offered a water libation by a male figure who is labeled “(his) son, Min.” Curiously, beneath the woman’s chair, there is a hieroglyphic text that reads Sat-re, meaning “Daughter of Re.” This could be the name of a female child whose image is no longer visible, or it could be an additional part of Henuttawy’s name.

Figure 15: Detail of the second register of the stela of Maienhekau in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266).

The third register shows another pair of seated figures (Figure 16). In this scene it is not the deceased Maienhekau and his wife who are shown, but instead, other members of Maienhekau’s family. The couple on the left are familiar to us from the other stelae of Maienhekau. His father, Min, sits with his mother, Ryry. In front of them, a man identified as “his son, Kha(em)waset” pours a liquid offering. On the right side, a man named Sennefer and a woman identified as “his daughter, Tamyt” are shown seated behind a table of offerings. Both seated men in this register hold lotus blossoms.

Figure 16: Detail of the third register of the stela of Maienhekau in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266).

The bottom register shows six kneeling figures (Figure 17). Each person faces right, and everyone holds a lotus in his or her left hand. Only one lotus is open; the rest are shown as buds. A hieroglyphic text to the right of each figure identifies them by name. From the left we have a woman named Ty, a man named Horus, a woman named Tanetabu, a man named Khaemwaset, a woman named Takhat, and a man whose name is missing. No titles or family relationships are given here to identify any of these people.

Figure 17: Detail of the fourth register of the stela of Maienhekau in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1266).

There are several different titles given for Maienhekau. Each title shows that he was a military man by occupation, but perhaps not a very high-ranking individual. Maienhekau held the general title of standard bearer. In some of the texts, this title is more specific, and he is referred to as the standard bearer of three different ships: Victory (in) Thebes, The Bellicose Cow, and Amenhotep the Bull Calf. For two of these vessels, he is also named as a commander. He holds this position for both Victory in Thebes and The Bellicose Cow. A final title he is given is that of the “bearer of arms of Menkheperre.”

The monuments of Maienhekau allow us to tentatively reconstruct his family tree and background (Figure 18). His parents were Min and Ryry. Two men, Khaemwaset and Sennefer, may have been brothers of his father Min, and are therefore uncles to Maienhekau. A woman named Meryt appears together with him on one stela, while another woman named Henuttawy accompanies him on all three stelae. It would be extremely uncommon for a non-royal official like Maienhekau to have two wives at the same time. In all likelihood, one of the wives, probably Meryt, died, and he then married a second time. It seems as if Maienhekau had nine children: his sons Nehemmeshaef, Mehu, Min and Khaemwaset, and his daughters Taryry, Tanetabu, Tamyt and Takhat. Traces suggesting a ninth child appear on the Louvre stela, but their name is lost. As for which wife is the mother of these children, only the daughter Tanetabu is explicitly connected to the woman Henuttawy. It is possible that this child was born to Henuttawy before her marriage to Maienhekau and that he then adopted the girl as his own. Unfortunately, the texts are not explicit enough for us to say with complete certainty. Two more people, a woman named Ty and a man named Horus, are included on the Glencairn stela, but there is no way to know with certainty what their relationship to Maienhekau was.

Figure 18: The family tree of Maienhekau.

Figure 19: Maienhekau’s name in hieroglyphs.

While nothing specific in the texts on these stelae gives us any indication of where Maienhekau came from, the decoration on the stela suggest that he (or his family) had connections to the city of Memphis. This important religious and administrative center was located in the northern part of the country, not far from Egypt’s modern capital, Cairo. All three of his stelae include an image of the god Ptah, the patron deity of Memphis. Ptah is not typically found on funerary stelae, so his inclusion here may be because of a special connection that Maienhekau felt towards this deity and the Egyptian city he protected. Perhaps Maienhekau originally came from the Memphite region. In any case, because he held positions that associated him with various royal ships, he probably would have spent a good deal of time near the ports and shipyards of Memphis, where these royal boats were moored when not engaged in military operations. Perhaps he developed a personal connection to the city’s patron deity.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section, Penn Museum

University of Pennsylvania

Bibliography

Al-Ayedi, Abdul Rahman. Index of Egyptian Administrative, Religious and Military Titles of the New Kingdom. Ismailia, Egypt: Obelisk Publications, 2006.

Chevereau, Pierre-Marie. “Le Porte-étendard Maienheqaou.” Revue d’Egyptologie 47 (1996): 9–28.

Faulkner, Raymond O. “Egyptian Military Standards.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 27 (1941): 12–18.

Gyllenhaal, Ed. “The Stela of Maienhekau.” Academy Museum Notes 10/3 (1986): 6–7.

Schulman, Alan Richard. Military Rank, Title and Organization in the Egyptian New Kingdom. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 6, Berlin: Hessling, 1964.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.