Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2024

Easter Eggs: Symbols of Rebirth and Renewal is a collaborative exhibition between the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University and Glencairn Museum. It opened on March 2nd and runs through May 5th.

Throughout the ages, the egg has captured the imagination of humanity in cultures and religions across the world as a symbol of the mystery of creation and the reawakening of the earth at springtime. Among the earliest surviving examples of human artistic traditions, decorated eggs have played a significant and perennial role in folk-cultural practices and religious expression up to the present day. Although the earliest written evidence of decorated eggs associated with the Christian celebration of Easter dates to the Middle Ages, this tradition was not simply a spontaneous development, but one that was shaped and influenced by a wide range of cultural practices throughout human history.

In a similar manner Pennsylvania’s vibrant Easter egg traditions emerge from a mosaic of diverse communities that have shaped and been shaped by broader transatlantic immigrant culture in America. The origins of decorating, blessing, and eating eggs as part of the religious celebration of the Paschal Feast in Pennsylvania can be traced to the arrival of several waves of immigrant groups beginning in the eighteenth century. Today Easter eggs have become a ubiquitous American tradition. Pennsylvania was the gateway for these traditions to enter North American culture, and continues to play a significant role as these cultural expressions evolve and new generations of Americans rediscover and explore their roots.

A traditional Pennsylvania Dutch pin-scratched goose egg, Pennsylvania, nineteenth century, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. This goose egg features sophisticated arrangements of floral and bird motifs, representing one of the most elaborate Pennsylvania Dutch scratched eggs to have survived from the nineteenth century. It was preserved by Joseph Kindig Jr. of York, Pennsylvania, who began collecting in the 1920s and became an influential expert in the material culture of the Mid-Atlantic.

German-speaking immigrants to Pennsylvania were the very first to establish a robust Easter egg tradition in North America.1 This transatlantic immigration gave rise to the popular Easter traditions that many Americans cherish today—decorated eggs, the Easter rabbit, Easter baskets, and egg hunts—all of which blend sacred and secular elements in contemporary celebrations of springtime. Later nineteenth- and twentieth-century migrations of families from Central and Eastern Europe brought their own unique Easter egg expressions to the Coal Region of Northeastern Pennsylvania, and to urban centers, such as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. For more than three centuries, these traditions have continued to flourish and diversify throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Myths of Creation and Rituals of Renewal

Human cultures have long admired the beauty and perfection of the egg, and marveled as new life hatches forth from the shell in springtime. Long before eggs were associated with the celebration of Easter, this mystery of nature came to represent new life and the reawakening of the earth each spring as a sacred symbol. The three-part structure of the egg, with its uniformly round shell, watery albumen, and brilliant yellow yolk, inspired stories of the creation of the earth, the oceans, and the sun in many religious traditions. The miraculous womb of the cosmic egg from which all life proceeds is a concept that appears in myths and sacred texts throughout human history.2

The oldest known written record of a mythological cosmic egg from which all life on earth proceeds is an ancient Egyptian manuscript from the New Kingdom Period (1580–1085 BCE), which praises the world-egg brought forth from the waters of nothingness by eight primeval deities: “O Egg of the water, source of the earth, product of the Eight, great in heaven and great in the underworld. . . I came forth with thee from the water, I came forth with thee from thine rest.”3 The egg contained the creator deity Atum, who fashioned the world from a mound of earth that emerged from the waters of chaos.4 In other versions of this creation story, it is the sun god Re who hatches from the egg,5 while still others suggest that the world-egg was laid by the goose Geb known as “the Great Cackler,” or the ibis associated with the god Thoth.

Ancient Egyptian ceramic egg in the Glencairn Museum collection, provenance and date unknown. This egg-shaped ceramic object in the Egyptian collection at Glencairn Museum, formerly part of the Academy of the New Church’s museum for at least a century, raises questions for researchers. It may be an ovoid juglet with a broken spout. However, its distinctive egg shape could hold symbolic meaning. According to two different versions of the Egyptian creation myth, the god who shaped the world hatched from a Cosmic Egg laid by either the celestial goose (known as the “Great Cackler”) or by the ibis associated with the god Thoth.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead includes many poetic incantations invoking the cosmic egg: “I have guarded this egg of the Great Cackler. If it grows, I will grow; if it lives, I will live; if it breathes the air, I will breathe the air.”6 It is significant that the cosmic egg of the world’s beginning also appears in these funerary texts, which served as a guide to souls navigating the afterlife. This is one of many instances throughout human history where eggs play a role not only in the symbolism of creation, but also in death and the hope of rebirth.

Paralleling the Egyptian creation stories, the Hindu creator god Brahma hatches forth from the Brahmanda (the cosmic egg), also called the Hiranyagarbha (golden embryo), which floats in the waters of creation. Among the oldest of the Hindu sacred texts is the Chandogya Upanishad, which describes the cosmic egg as hatching into two pieces, one silver and one gold, which became the earth and sky.7 Later writings such as the Visnu Parana and Brahmanda Purana describe that after a period of one thousand years of incubation, Brahma emerges from the seven-layered egg shell to create the universe, the sun, moon, and planets; the oceans, continents, and mountains; as well as the animals and humans— all from the matter of the egg.8

The Nihon Shoki (Japanese Chronicles) from 720 CE describe a similar creation story in which a cosmic egg was formed of the undifferentiated feminine and masculine principles, In and Yo, which separated to form the heavens and the earth.9

Likewise, in some variations of the Orphic creation myths of the ancient Greeks, the cosmic egg is separated into two halves that form the earth and sky.10 Considered the first Greek religious movement to produce sacred texts,11 the poetry of the Orphic traditions describe that in the beginning there was a watery abyss. Time, personified as a serpent or dragon and moved by Necessity, produces Aether and together with Chaos, gives birth to a cosmic egg. The serpent Time squeezes the egg, and hatches forth the shining creator god Phanes, both male and female, who gives birth to the gods, and thus all of creation.12

It is this ubiquitous notion of the cosmic egg, combining feminine and masculine forces and thus all of material existence, that inspired philosophers and later alchemists to envision the prima materia or first matter as the source of the four elements, containing within it the opportunity of the perfection of nature in the philosopher’s stone.13

A celebrated white marble relief at the Galleria Estense, Modena, depicts the hatched solar god standing within the celestial and terrestrial hemispheres of the cosmic egg—one crowning their head and the other supporting their feet, while a serpent forms a spiral around their body. Echoing the shape of the cosmic egg, an ovoid aureole containing the twelve signs of the zodiac delimits the celestial sphere, and personifications of the four winds gaze from each corner.14

The Modena relief is presumed to be a Roman syncretic work from the second century CE, likely equating the Orphic god Phanes with Mithras, a solar god who also hatched from the cosmic egg.15 Archaeologists have long observed parallels between the stories of Mithras and Jesus in the observation of their birth on December 25,16 although perhaps the most unexpected of these instances is a carved stone fountain in Alsleben bei Zerbst, Germany, depicting the resurrected Christ emerging not from a stone tomb, but from the shell of an egg, as a symbol of rebirth.17

Roman marble relief of Phanes-Mithras hatching from the cosmic egg, forming the heavens and the earth from the eggshell, surrounded by the twelve signs of the zodiac and the four winds. Italy Emilia Romagna Modena: Estense Gallery. Alamy Stock Photo: Claudio Pagliarani.

While this particular artistic rendering of the cosmic egg is highly unusual for Christian art, it serves as a visual parallel to the egg’s symbolic role in stories of both the creation of the cosmos, as well as the renewal of the world through rebirth. This association of the egg with resurrection is likewise a feature of many cultures, featured especially in the rich imagery of funerary arts and practices of ancient cultures throughout the world.

Archaeologists discovered Ostrich eggs in ancient Egyptian tombs of the Predynastic Period dating to the fourth millennium BCE, including both plain and highly decorated examples.18 Although it is uncertain whether these eggs were meant to be interpreted literally as food offerings to the dead, as functional containers, or specific symbolic objects, their sustained presence in burials throughout Egypt and beyond into the Mediterranean and Western Asia suggest a direct connection with religious veneration of the dead and hopes for an afterlife.

In the tomb of the Pharoah Tutankhamun, who reigned from 1347–1337 BCE, a sculptural lid of a funerary jar depicts a young goose with four unhatched eggs, likely referencing the creation story of the Great Cackler and the cosmic egg.19 Ostrich eggs cut into the shape of libation cups appear in Mesopotamian gravesites at Kish from 3000 BCE, and ostrich eggs also appear as funeral offerings in Assyrian graves at Assur from 2000 BCE.20 Similar ostrich egg bowls dating to the second or third century BCE were discovered in Los Millares, Spain.21

Recent archaeological discoveries of decorated ostrich eggshell fragments at the Diepkloof Rock Shelter in Western Cape, South Africa, dating from roughly 60,000–75,000 years ago, suggest that the decoration of eggs is perhaps humanity’s oldest surviving artistic tradition. To scientists, this discovery at Diepkloof is the earliest known example of human decoration and “constitutes the most reliable collection of an early graphic tradition.”22 The colorful egg fragments display a wide range of patterns etched into the surface of the shell that may hold symbolic or functional significance in addition to artistic expression.

Robin’s eggs and nest, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. Human traditions of egg decoration draw inspiration from the colorful eggs of birds worldwide. Robin's eggs are among the most brightly colored, and robin migrations signify the arrival of spring. In European art, robins are linked to the Paschal (Easter) mystery, their red breast symbolizing Christ's blood. According to some legends, a robin's breast turned red when it felt compassion and tried to remove thorns from Christ’s crown, but in doing so, pricked its own breast.

These earliest decorated eggs are reminders that humanity’s story has been interwoven with the egg in both sacred and mundane contexts long before the advent of agriculture and urban settlements. The consumption of eggs by humans is a practice inherited from our hominid ancestors, dating back millions of years.23 Prior to the widespread domestication of chickens in the Neolithic period first developed in China, the eggs of quail and other related species such as pigeons were eaten by hunter-gatherers, and these birds were among the first to be domesticated following the establishment of cities.24 According to the Book of Exodus, great migrations of quail fed Moses and the Israelites in the wilderness for forty years, 25 and quail were prized for their eggs and meat in Ancient Egypt, where the birds were depicted in art, both as the hieroglyphic letter ‘w’ and in images of migrating flocks in natural habitats. 26 Later, the Egyptians were the first culture to develop robust egg incubation techniques using wood-fired brick ovens, which not only increased flocks of domesticated fowl, but dazzled visiting foreigners who marveled at the process.27

Like the ancient art of the Egyptians, eggs also appear in burial paintings of the Etruscans dating from the eighth to the third centuries BCE. Here the egg plays an enigmatic roll, depicted in a ritual of passing eggs from one figure to the next. Archaeologists have also discovered decorated scratched ostrich eggs, as well as eggs etched onto funerary mirrors, painted on pottery urns, and ritually roasted in braziers by tombs, presumably as both offerings to the dead and as food for mourners.28 Funerary statues from the third century BCE in Boeotia depict the Greek god Dionysus holding an egg and a rooster,29 as if begging the age-old question: “Which came first?” Funeral vases at Athens depict baskets of eggs left on graves as offerings to the deceased, and in keeping with traditions of holding annual meals of remembrance at grave sites. Similar feasts are documented in ancient reliefs in Syria.30

Red egg, dyed with onion skins, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. Eggs dyed red played significant roles in religions and cultures throughout the ancient world, including the Jews, Greeks, Persians, Chinese, and later by Yazidi Kurds and Christians. Typically dyed with onion skins and a small amount of vinegar to bind the dye to the shell, the eggs were hard boiled in the dye, and remained edible with a touch of onion flavor to the egg. This is also the traditional way to dye eggs among the Pennsylvania Dutch, Ukrainians, and Lithuanians.

Even today among the Kurdish Yazidis, the New Year’s celebration on “Red Wednesday” in mid-April is signified with the ancient practice of dyeing eggs, which are exchanged and also placed on family graves. This practice is based in the Yazidi belief that the world was hatched from an egg by an archangel in the form of a peacock.31 At the celebration, eggs are cracked together in games to simulate the birth of the world from the egg. The Persian celebration of the new year is also celebrated with the dyeing of eggs, and according to some is called “The Festival of Red Eggs.”32

It is clear that even for ancient cultures that did not venerate their dead with devotional offerings, eggs still featured prominently as both ritual foods and symbols of renewal. According to Jewish tradition, eggs and bread were eaten at meals of condolence (seudat havrah) following burial of the dead as food to comfort the mourners.33 In some Jewish communities, such as those in Morocco, “mourning eggs” were dyed with onion skins and eaten at Sukkot or the autumn Feast of Tabernacles.34 Similarly, hard boiled eggs dipped in ashes are eaten as part of an old Ashkenazi custom before fasting on the holy day of Tisha B’Av, observed in remembrance of the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem.35

Eggs also played a significant role in the celebration of pesach or Passover, which celebrates the Exodus from slavery in Egypt. At the Passover Seder meal, a roasted egg called the betzah represents the hagigah or burnt offerings prior to the destruction of the temple.36 It appears, however, that for both the Seder and Tisha B’Av, eggs not only represented the loss of the Temple and the ritual of the burnt offering, but also a sense of hope in transformative renewal.37 Some Jewish traditions point to the roundness of the egg as a symbol of hope, as well as the cycle of life and renewal.38

It is perhaps precisely this dual meaning, as both a food of mourning and hope for renewal, that eggs first appear in early Christian legends of the Resurrection. As devout Jews, Jesus and his disciples celebrated the feast of Passover according to the biblical narratives on the night before his arrest by the Romans, and subsequent Crucifixion the following day. Among Eastern Orthodox Christians, the name for the celebration of Easter as Paska (Ukraine) and Pascha (Greece) takes its name from the Hebrew Pesach, and is the origin of the word “Paschal” used to alternately describe both Passover and Easter traditions. This overlap dates back to the time when early Christians, especially those of the Byzantine Church of the East, continued to celebrate Easter at the time of the Jewish Passover. It was not until the Council of Nicea in 325 CE that the observation of Easter was no longer reckoned according to the Jewish calendar for both Roman and Byzantine Christians.39

Orthodox Christians and some Catholics attribute the origin of the Easter egg to a miracle observed by St. Mary Magdalene, who was the first to witness the Resurrection in the Gospel narratives.40 According to tradition, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb to anoint the body of Jesus and brought a basket of hard boiled eggs as the traditional food of mourning. To her surprise, she found that the stone had already been rolled away and the eggs in her basket had miraculously transformed to the colors of the rainbow.41

Another story describes that Mary Magdalene presented an egg to the Roman Emperor Tiberius in an attempt to spread the news of Christ’s Resurrection. The emperor replied that a human could no more rise from the dead than the egg in her hand could turn red, and at once the egg was said to turn crimson red.42 It is for this reason that Eastern Orthodox icons of St. Mary Magdalene depict the saint holding a bright crimson egg. Eggs also play a role in other forms of veneration of St. Mary Magdalene, where an unusual pilgrimage site in France is called Grotte aux Oeufs (the Cave of Eggs), and is located in the mountains of Sainte-Baume in Provence, not far from an official shrine where, according to legend, St. Mary Magdalene spent her final days after fleeing Palestine.43

St. Mary Magdalene and the egg, Ukrainian Orthodox icon, 2023, Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer, Kutztown, Pennsylvania. Some Orthodox Christians and Catholics attribute the origin of the Easter egg to a miracle by St. Mary Magdalene, the first witness to the Resurrection of Christ in the Gospel narratives. According to tradition, Mary Magdalene presented an egg to the Roman Emperor Tiberius to spread the news of the Resurrection. The emperor responded that a human could no more rise from the dead than the egg in her hand could turn red. But the egg reportedly turned crimson red instantly. In other stories, Mary Magdalene brought a basket of hard boiled eggs to hold vigil at the tomb of Jesus. When she arrived, she found the stone that had covered the tomb rolled away, and the eggs in her basket had turned red.

In other traditions, it is the Blessed Virgin Mary as the source of the Easter egg tradition, who brings a basket of eggs to the foot of the cross, where she begs for mercy for her crucified son, and the drops of his blood turn the eggs red.44 A different legend suggests that Mary decorated eggs at the time of the Nativity, reinforcing the common Eastern Orthodox practice of depicting the Madonna and Child on Easter eggs.45 Yet another legend suggests that the Virgin Mary’s tears of joy colored a basket of eggs brought to her as food of comfort when she learned of her son’s Resurrection.46

It is likely that these legends are not of antiquity but of late arrival to Christianity as a way to differentiate the practice of decorating eggs among Christians from the many cultures that also decorate eggs at springtime. As indicated by the sheer proliferation of egg myths and egg decoration traditions throughout the world, such practices would not have been out of the ordinary.

As evidence of this ubiquity, throughout the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East, ostrich eggs were historically suspended in houses of worship across many faiths, including mosques, Coptic Christian churches in Egypt, and Greek Orthodox Churches, where a variety of stories explain their appearance as symbolic of various theological concepts or as serving a ritual function to bless those who enter the sacred space.47 Among such holy locations was the shrine of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, where ostrich eggs were historically suspended as a symbol of the Resurrection.48 In some instances, ostrich eggs were produced in porcelain, such as those which once hung at the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, Egypt. Some have suggested that these ceramic eggs served as counterweights for hanging lamps, while others have inferred a dual function as exotic objects of value and as religious symbols of devotion and rebirth.49

An Italian fresco at the Tomb of Antonio die Fissiraga (d. 1327) in Lodi, Lombardy, depicts an ostrich egg, either natural or ceramic, hanging from a chain above the seated Madonna and Child, to whom Fissiraga presents the image of a church, accompanied by St. Francis and another saint.50 Ostrich eggs have also appeared on official historical church inventories of liturgical items, including two at St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome by a donation of Pope Leo IV (847–855),51 and later in the shrine of the powerful Medici family in Florence in 1492.52

Ostrich egg, private collection of Becca Munro, Harleysville, Pennsylvania. In the Mediterranean and the Middle East, it was a tradition to hang ostrich eggs from the ceilings of religious places, including mosques, Egyptian Christian (Coptic) churches, and Greek Orthodox churches. These eggs symbolized theological ideas or served to bless those entering sacred spaces. In some cases, the ostrich eggs were made from porcelain, like the ones that decorate hanging lamps at St. Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the use of eggs as significant focal points in sacred architecture continued and may have even influenced aspects of liturgical practice. In Germany, ostrich eggs were placed on a representation of the holy tomb in the liturgy of the Easter Vigil mass, mirroring those documented at the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Priests would take the eggs and place them on the alter while intoning the Paschal greeting at midnight: “Christ is Risen,” met with the congregations reply, “He is risen indeed.” This signified the beginning of the Easter celebration, and the end of the Lenten fast. Such practices were historically associated with Cathedrals in the German cities of Mainz and Halle, and even continued into the eighteenth century at Cathedrals in Rheims and Rouen.53

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the development of the egg’s role in the Easter celebration lies in its historical ritual prohibition during the season on Lent, and the subsequent blessing of eggs at the Easter Vigil. Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) established the Lenten fast as a time when “. . . we abstain from flesh meat, and from all things that come from flesh, as milk, cheese, and eggs,”54 and the period of the fast eventually encompassed the 40 day period extending from Ash Wednesday through Holy Saturday, when the Easter Vigil was held. The liturgy of the vigil included special provisions for the blessing of eggs, salt, and bread, which were brought to church to be consecrated and subsequently eaten to break the Lenten fast:

“Lord, let the grace of your blessing come upon these eggs, that they be healthful food for your faithful who eat them in thanksgiving for the Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you forever and ever. Amen.”55

Eggs blessed in church were distributed in the community, and Christians of both Eastern and Western traditions placed eggs on family altars as a blessing to the home, concealed them in agricultural buildings, and ate them as rituals for health and well-being.56 Cracking games, practiced by children and adults, made use of the abundance of eggs prepared for the celebration, and the cracking of eggs symbolized a celebratory “hatching” of new life and the coming of spring.

It was a common custom dating to antiquity to dye such eggs red in onion skins as part of the Paschal celebration, but the decoration of eggs does not appear in written texts until the thirteenth century, when two references from the Slavic and German cultures appear. Archbishop of Kraków, Wincenty Kadłubek (1160–1223), writes of the turmoil in Poland, that “since antiquity, the Poles . . . play with their lords as if they were painted eggs.”57 In 1216 CE, German poet Freidanck penned the lines in Middle High German: “Ein kint næme ein geverwet ei vür ungeverweter eier zwei” (A child takes one colored egg, [but] for uncolored eggs, [the child takes] two).58

In both early texts, the authors refer to decorated eggs in mundane terms, indicating that the practice was commonplace. It is perhaps small wonder then, that archaeological discoveries of decorated ceramic eggs and colored egg shells in Ostrówek, Poland from ca. 1000 CE, and colored ceramic eggs at Worms, Germany from 320 CE, suggest that such practices had been well established among both Germanic and Slavic peoples, even prior to Christianity.59 Despite innumerable changes in cultural attitudes, materials, techniques, and significance, the tradition of decorating eggs has continued to grow and evolve in communities throughout Eastern and Western Europe.

Immigrants eventually brought these traditions to North America, where they flourished in folk-cultural communities spread throughout Pennsylvania. As the most ethnically and religiously diverse of the original thirteen colonies, Pennsylvania provided a safe haven for immigrants whose traditions continue to flavor the diversity of the commonwealth to the present day.

A traditional Pennsylvania Dutch scratched goose egg, by Peter V. Fritsch, Longswamp, Berks County, ca. 2005, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. This scratched goose egg features the artist Peter Fritsch's signature image of a bird poised on a flowering branch, as well as the blossoming of an intricate sunflower at the top, and a rosette on the bottom—all traditional motifs of the Pennsylvania Dutch.

Pennsylvania Dutch Easter Eggs

Prior to the American Revolution, 81,000 emigrants from the German-speaking regions of Central Europe established communities in early Pennsylvania before spreading throughout North America.60 Known by their English-speaking neighbors as the Pennsylvania Dutch, these immigrants brought their distinctive language, religious traditions, and seasonal customs to North America, where they both contributed to and were shaped by the blossoming of a new American identity. Their cultural influence is still visible today through the widespread adoption of holiday customs that later rose to popularity in the United States, especially those of Christmas and Easter. Among these, Easter eggs and the Easter rabbit stand out as two distinctive contributions to American culture.

Although many Anglo-American traditions are echoes of the British colonial past of early America, comparatively few of the quintessentially American holiday expressions, such as those of Easter and Christmas, find their origins in the British Isles. German cultural expressions, such as the Easter rabbit and Easter egg hunts, though popular today, were once considered foreign, unfashionable, or alternately too Catholic or too secular for the tastes of the Quakers, Presbyterians, Puritans, and some sectarian communities in Pennsylvania. As Dr. Alfred L. Shoemaker observed: “It must be remembered that the vast majority of the early British settlers in the Commonwealth—the English Quakers, and the Presbyterian Scotch-Irish—did not celebrate Easter. In fact, they ‘shunned’ it.”61 These Easter traditions nevertheless spread throughout the North American continent by way of the German-speaking immigrant communities, setting the stage for a new American expression of holiday traditions that would grow and change over many generations.

As a predominantly Protestant culture, Pennsylvania Dutch communities were composed of roughly 95 percent members of Lutheran and Reformed congregations, while just 4 percent were members of sectarian Anabaptist and pietist groups, including the Mennonites, Amish, Brethren, Moravians, and Schwenkfelders. Less than one percent were Roman Catholics. As a result, the official religious expressions of the Pennsylvania Dutch were considerably less liturgical than their communities of origin in Europe, yet their folk-culture was still deeply rooted in centuries-old, pre-Reformation beliefs and observances associated with the old liturgical and agricultural calendar.62 Easter eggs therefore made no official appearance in early Pennsylvania churches but were relegated to the home, where eggs were gathered in large quantities in the weeks leading up to Easter to be dyed, scratched to produce elaborate designs, and given as gifts among friends and family on Easter Sunday.63 Although not formally cultivated by the church, Protestants, Anabaptists, and Pietist religious groups in Pennsylvania decorated eggs as part of their annual Easter celebrations.

Pennsylvania Dutch Easter eggs by Peter V. Fritsch, ca. 1975–2010, Longswamp, Berks County, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, gift of Peter V. Fritsch. The prolific Pennsylvania Dutch artist and poet Peter V. Fritsch (1945–2015) created these Easter eggs as part of his annual tradition of handcrafting tokens of appreciation for his friends and family. Rooted in both traditional and contemporary artistic expressions, Fritsch’s work evokes the connection of local culture with the land and the cycles of the seasons. His work features depictions of birds, plants, and creatures of the earth, along with geometric motifs inspired by stars and religious symbols. Using a variety of scratched and painted techniques, Peter Fritsch’s work embodied both the continuity and evolution of Pennsylvania Dutch Easter egg traditions.

Good Friday Eggs

It is uncertain whether eggs were ever brought into the sanctuaries of early German Catholic or Episcopalian churches in Pennsylvania as tradition would have dictated in Europe, where portions of the Easter meal, including eggs, bread, and salt, were blessed at the Easter Vigil, and even sprinkled with holy water in the early days.64

Originally intended to bless food for actual consumption, according to tradition, congregants sometimes kept small samples of such consecrated eggs, salt, and bread long after Easter in households across Europe. The eggs were considered useful for a wide range of practical concerns, including healing, protection, and divination. Eggs laid on Maundy Thursday or Good Friday that were dyed red and blessed in the church were often kept hidden or displayed in household shrines to protect the home. Some of these eggs were inscribed or decorated with crosses to enhance their potency as sacred objects.65

These unofficial, folk-cultural European beliefs and practices provide insight into American customs among the Protestant Pennsylvania Dutch communities in Pennsylvania, where acts of ritual consecration no longer occurred in church during Lent and Holy Week, but took place on an unofficial, folk-cultural level at home and on the farm as sacred expressions for blessing, protecting, and promoting the well-being of humans, animals, and cultivated plants.

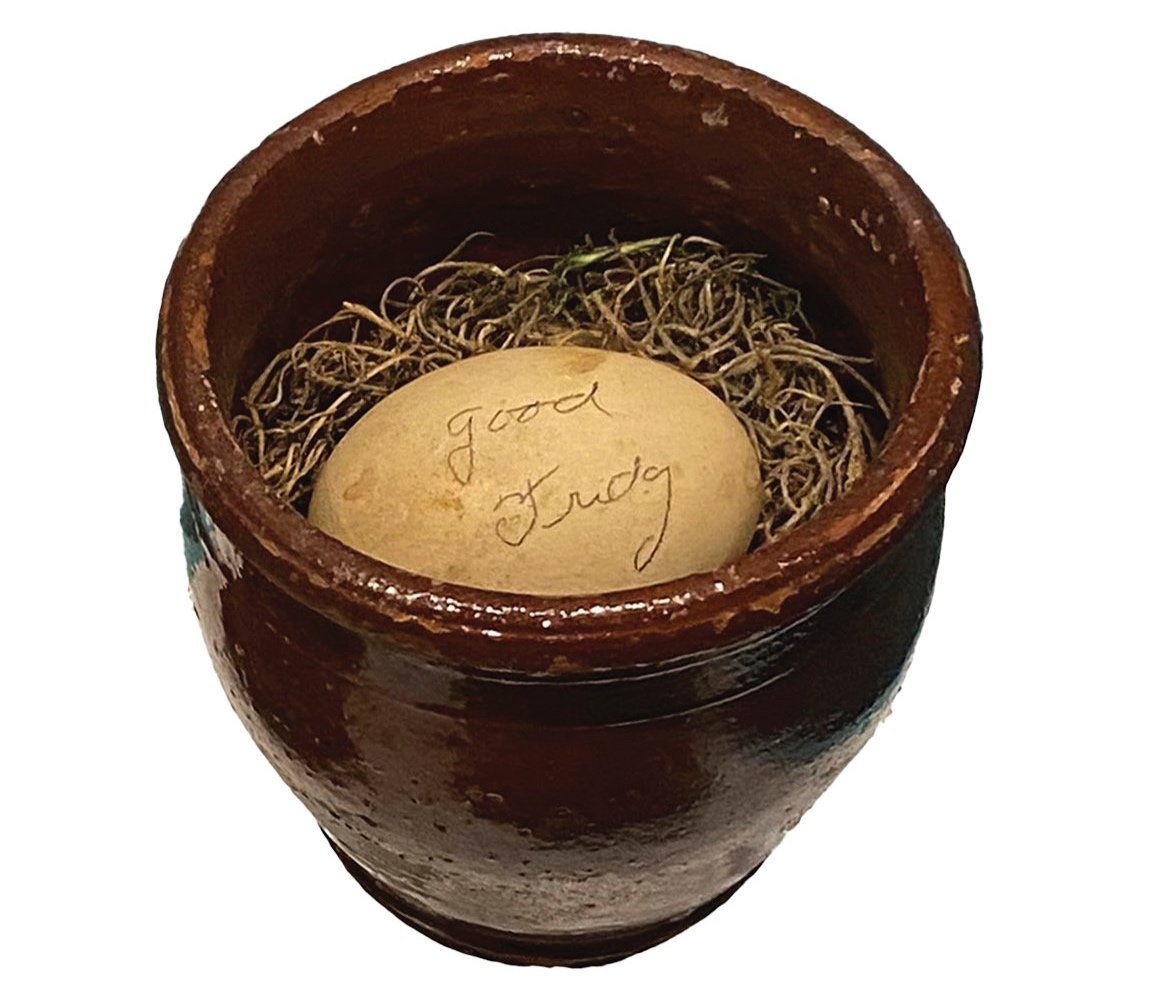

Good Friday egg (Kaarfreidaagsoi), Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, gift of Carl and Minerva Arner. Emma Koenig of New Ringgold, Schuylkill County, gathered this Good Friday egg in the late twentieth century, and each year she placed one in the barn, farm house, coops, and sheds on the farm to bless and protect the buildings and their occupants from storms, lightning, and fire.

When the Lenten season commenced on Ash Wednesday, not only were ashes applied to the foreheads of the faithful in church, but farmers also dusted their cattle, gardens, and even the perimeter of homes with ashes from the woodstove to drive away parasites, insects, rodents, and snakes.66 On the prior day, Shrove Tuesday, farm families used leftover lard from frying Fasnacht donuts to ritually anoint garden tools and plows to ensure an abundant agricultural year and to protect the soil in the kitchen garden and grain-fields from pests.67 Later during Holy Week, wild dandelion greens were gathered and eaten on Maundy Thursday to impart the blessings of Griener Dunnerschdaag (Green Thursday), which commemorated the Holy Supper, when bitter greens were eaten by Jesus and his disciples as part of the Jewish observation of Passover.68 Eating greens on this day was believed to prevent lethargy and illness in early spring.69

Good Friday was the most auspicious of these Lenten days, when no work of any kind was to be done, with the exception of the utmost necessities in caring for livestock. Instead, Pennsylvania Dutch families kept busy with a wide range of holiday observances and rituals. According to folklore, it always rained (even just a little bit) on Good Friday,70 and rural families collected such consecrated rainwater, and even dew, in jars to prevent illness and for the baptism of children in some rural union churches in Berks County.71

Most significantly, however, the Pennsylvania Dutch considered eggs laid on Good Friday to be intrinsically holy and were set aside to be eaten for breakfast on Easter morning to prevent illness.72 On many local farms, families selected an egg consecrated by virtue of this special day, and hid it in a container in the attic of the farmhouse to protect the house from storms, lightning, fire, and illness. One contact from Schuylkill County recalled that an egg was placed in each building on the farm, including the house, barn, sheds, coops, and other outbuildings.73 A good Friday egg could also be employed to relieve a hernia or to reduce a fever, and several contacts from the border of Berks and Lehigh counties not only recalled this practice but saved the delicate Good Friday eggs for decades in observation of this annual practice.74

While most Good Friday eggs were kept perfectly white and fresh, with occasional inscriptions for the year they were collected, on rare occasions, some were also hard boiled and dyed red, along with ordinary Easter eggs prepared on Holy Saturday for the celebration the following day. Among the Pennsylvania Dutch, Easter eggs generally fell into two main categories: those that were intended for eating and those featuring a wide range of decorative motifs that were presented as gifts. Both classes of Easter eggs were typically hard boiled in natural dyes.

Like their ancestors in Europe, the Pennsylvania Dutch boiled their Easter eggs with the skins of yellow onions. A small amount of vinegar was used to bind the dye to the calcium of the shell. Depending on the concentration of the dye, onion skins produce a limited range of warm colors from orange to deep red or brown. These colors also varied depending upon the breed of chickens, and whether the hens laid white, brown, or pale blue eggs. Like many other European cultures, the Pennsylvania Dutch considered the traditional red resulting from onion skins to be significant for Easter eggs because of the color’s association with the blood of Jesus shed at his Crucifixion on Good Friday.

Other colors were also historically produced from black walnut hulls, coffee or oak bark for shades of deep brown to black, and hickory bark or elder catkins for yellow.75 Shredded red cabbage or dried hibiscus flowers, which if boiled and allowed to oxidize, formed a deep emerald green, while dried elderberries, currants, or pokeberries could be reconstituted for shades of magenta, and roots such as turmeric or beets produced yellow and pink.

A traditional Pennsylvania Dutch scratched Easter egg, twentieth century, Berks County, private collection of Elaine Vardjan. Scratching eggs is a living tradition among the Pennsylvania Dutch, and is also one of the earliest types of Easter egg decoration documented in America among the descendants of German-speaking immigrants to Pennsylvania. The contents of this egg were blown out, and a cord was attached to hang the egg.

If natural dye plants were shredded and kept in the dye bath at the time of boiling the eggs, this produced mottled colors, especially onion skins, which created a variegated appearance if left in close contact with the eggs. A uniform color could be achieved with dye plants that were boiled and strained to remove them from the dye bath. The Pennsylvania Dutch dyed not only chicken eggs with these methods, but also goose, duck, turkey, guinea and peahen eggs.

Families saved any eggs that cracked in the boiling process for eating, while those considered suitable for decoration were carefully selected to ensure their quality. Rich colors, especially deep reds, greens and browns, were favored for traditional scratching techniques that produced high-contrast decorative forms. A pen knife or a pin with the head firmly pressed into a cork worked perfectly to remove portions of the dyed surface, revealing the white of the shell underneath.

The entire family—women, men, and children—participated in this delicate art form. Eggs presented as gifts for family and friends were typically inscribed with names, initials, dates, and artistic designs, and youths exchanged decorated eggs as tokens of affection. Such delicately inscribed Easter eggs were highly personalized and varied considerably from one individual to the next, and some of these eggs serve as heirlooms, recording the family history as a unique form of documentary material culture. Among historic examples in Pennsylvania, a wide range of both representational and abstract forms appear, and while birds, flowers, and star patterns are among the most numerous, other documented examples include images of animals, people, angels, and religious iconography, along with houses, agricultural implements, and even grandfather clocks—images connecting families to their lived experiences in the world.76

Binsegraas Easter egg, Berks County, by Viola E. Miller (1916–1982), ca. 1960, private collection of Elaine Vardjan, Oley, Berks County. A traditional form of appliqué Easter egg decoration in Pennsylvania involves carefully removing long strands of the inner pith of bulrushes and applying it to the egg’s surface, along with fabric accents applied below the pith, or as surface elements on top of the pith.

Applied Easter Egg Decorations

In addition to egg scratching, the Pennsylvania Dutch employed several other techniques to decorate Easter eggs, including the use of applied patterned fabrics or the pith of the common bulrush known as Binsegraas, which can be carefully removed and adhered to the surface. There are two basic techniques for applying strands of rush pith. Either the egg features fabric cutouts that are tightly framed in spirals of pith, or the pith wraps the entire egg in tight spirals and applied fabric cutouts embellish the surface. Although both forms were once commonplace in Pennsylvania, the latter technique was once favored in the twentieth century by the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County.77

The use of Binsegraas in Pennsylvania has all but vanished. The technique relies upon a ready supply of bulrushes harvested from wet meadows, and according to local lore, the best bulrushes are to be found where cows fertilize them with their manure.78 The rushes then have to dry, and the pith is painstakingly removed by forcing a wooden match stick along the rush while simultaneously splitting the outer cylindrical husk of the grass. Long strands of pith are best to work with, but require patience and skill to properly remove it. Two of the foremost artists continuing this practice in Pennsylvania are Elaine (Becker) Vardjan and her daughter-in-law Nancy Vardjan of Oley, Berks County.

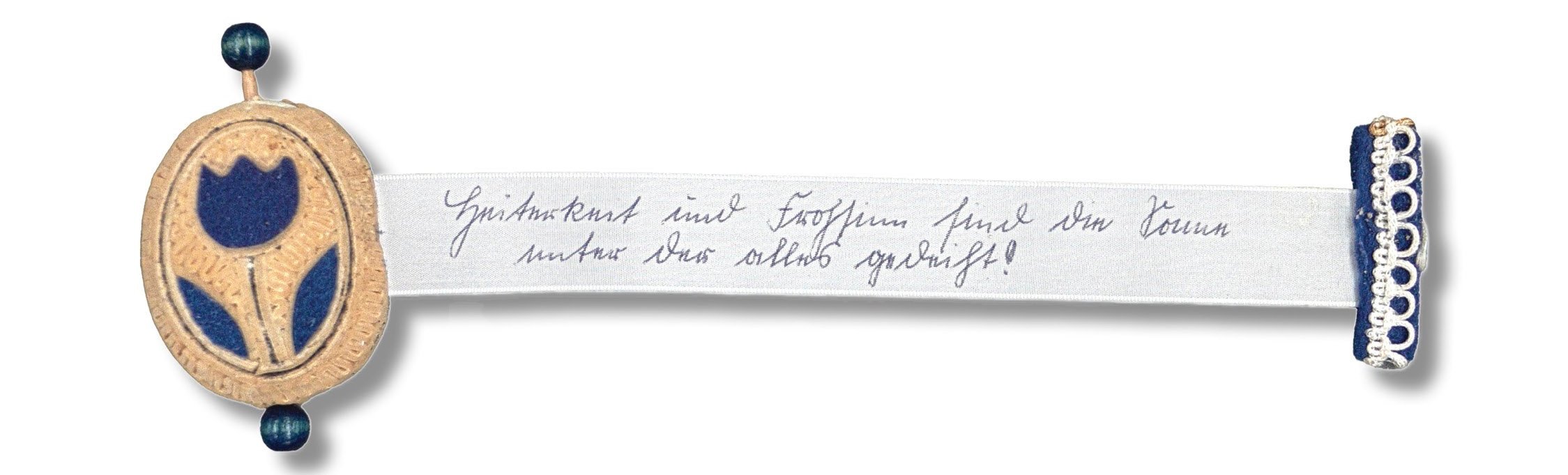

German Binsegraas Easter egg, Berks County, twentieth century, private collection of Elaine Vardjan, Oley, Berks County. This German Easter egg displays an intricate use of bulrush pith and fabric to form a tulip, with a slot for a concealed scroll to extend out from a spool in the egg that provides the German text: “Heiterkeit und Frohsein sind die Sonne unter der alles gedeiht!” (Merriment and gaiety are the sun under which all things thrive!).]

The use of rush pith is a tradition that is found on both sides of the Atlantic, especially in German-speaking communities, where the practice is accompanied by folk beliefs that the phase of the moon affects the quality of the pith. According to German sources, the rushes must be picked at full moon when the pith is at its prime, otherwise, the reeds will be empty when the moon wanes.79 The practice has been documented in Göttingen and other parts of Germany,80 as well as Poland, where in Silesia, they combine the pith with strands of wool.81 One German variety of the pith-covered egg includes an inscribed ribbon that unrolls like a scroll from a rod inserted into holes at the top and bottom of the egg, and emerges from a slot on one side. The messages tend to be sentimental or inspirational, in keeping with the egg’s role as both a token of affection and a sacred object.

Redware Easter eggs and charger, Lester Breininger, Berks County, 1979–2006, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, and private collections of Elaine Vardjan and Ruth Laubenstein Yablonski. Lester Breininger (1935–2011) was the leading Pennsylvania Dutch redware potter of the twentieth century. He opened a pottery workshop in Robesonia, Berks County, in 1965. With roots tracing back to German-speaking settlers who arrived in Berks County in 1712, Lester, a ninth-generation descendant, aimed to bring back early techniques, materials, and styles in both practical and decorative items. Each year, he made redware Easter eggs with bright yellow slip and carved patterns that revealed the red clay beneath. This technique, called sgraffito, parallels the colorful scratched eggs in the Pennsylvania Dutch tradition.

Historic Pennsylvania Easter Eggs

Although it is likely that thousands of Easter eggs have been decorated each year in Pennsylvania throughout the past three centuries, seldom do these fragile decorated eggs survive from one generation to the next. Part of the reason for this is that previous generations decorated hard boiled eggs that gradually dried out. Unlike today’s practices of hollowing out the egg shells by blowing out the yolk and white, the Pennsylvania Dutch tradition involved leaving the egg entirely intact. The white would gradually dry out, and the yolk would become solid and rattle inside the shell. Normally such eggs would dry completely in a few years, with minimal, if any, odor. The only exception to this, is if any imperfections compromised the shell, such as accidental weak spots from scratching or using too much vinegar in the dye when hard boiling, which would cause the egg to leak and putrefy. Eggs had to be kept in a stable, dry environment, such as a cupboard, a small box, or on the mantle, where they would be preserved.

A traditional Pennsylvania Dutch pin-scratched duck egg, Pennsylvania, nineteenth century, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. This pin-scratched duck egg features the images of a delicately articulated bird. The shell was dyed red-brown with the traditional onion skin vinegar dye. This egg is one of two preserved by collector Joseph Kindig Jr. of York, Pennsylvania.

Typically only the most decorative of eggs would be saved from year to year, as a common Pennsylvania Dutch-language proverb ominously states: “Friehyaahr iss net do, bis die Oschderoier gesse sinn” (Spring is not here until the Easter eggs are all eaten).82 Although spoken in jest, this proverb accurately represents the gusto which once marked the festivities of Easter day, when children and youths not only exchanged eggs, but commenced competitive activities to gather and eat as many eggs as possible. These traditions include annual egg eating contests or a competitive game called “egg picking,” in which two eggs were struck against one another and the egg that survived the encounter was determined the winner.83 Competitive children selected eggs for their shape and hardness of shell in the hopes of qualifying as the local champion. Those that won such contests got to keep the eggs of their opponents. Combined with annual egg-eating contests, it is small wonder that so few Easter eggs survived from previous centuries. The Juniata Sentinel & Republican newspaper reported on April 22, 1874 that a “champion egg-eater lives in Ephrata. . . last Easter he ate 40 and still lives.”84

Although these games usually included only the simplest dyed hard boiled eggs, still the overwhelming majority of the Easter eggs produced in Pennsylvania throughout the centuries were broken and didn’t survive. Early Easter eggs preserved by families, private collectors, and cultural institutions are a rarity. Some of these are from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, while very few examples from the eighteenth century still exist. The ephemeral nature of the tradition was the subject of much attention in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century newspapers throughout Southeastern and Central Pennsylvania, where editors queried their readers to find stories of the oldest Easter eggs in Pennsylvania communities.

Scratched Pennsylvania Dutch Easter egg, Strodes Mills, Mifflin County, 1844, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. In 1844, George and Susanna Strunk of Strodes Mill, Mifflin County, crafted a traditional scratched Easter egg for their two-year-old son, A. James Strunk (1841–1871). Using onion skins, they dyed the egg a russet red color and decorated it with flowers, stars, an owl, a turtle, a bird, the initials “A. J. S.,” and the date. The egg has been passed down by members of the family for generations, a rare survival from that time due to the fragility of natural eggs.

An excellent example of a traditional scratched egg surviving from 1844 was made by George and Susanna Strunk of Strodes Mills, Mifflin County, for their son A. James Strunk (1841–1871), when he was just two years old. They dyed the egg with onion skins for a russet red color, and adorned it with flowers, stars, an owl, a turtle, a bird, and the initials “A. J. S.” and the date. The egg was passed down by members of the family for generations and was eventually featured in several newspaper articles in Mifflin County as one of the oldest surviving eggs in the region. A newspaper clipping preserved by the family, dated April 17, 1963, shows Mrs. Margaret M. Strunk holding the egg that had belonged to her grandfather A. James Strunk. Another clipping from 1960 indicates that Mrs. Strunk had displayed the egg, then 116 years old, in her office at the Lewistown Insurance & Realty Company, which drew attention from the public and the local press.85

While the Strunk egg is one of only a few eggs that survived from the mid-nineteenth century, eggs from the eighteenth century are exceptionally rare in Pennsylvania Communities. The Lancaster Daily Express on March 27, 1875, reported the survival of an Easter egg scratched 100 years prior, when Easter was celebrated just three days before the Battles of Lexington and Concord at the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775.86

In 1960, Dr. Alfred Shoemaker of the Pennsylvania Folklife Society located an article published in 1884 in the Mount Joy Herald including an account of yet an older egg. Jacob N. Brubaker (1832–1913), bishop of the Lancaster Mennonite Conference and member of the Landisville Mennonite congregation, described an egg formerly owned by Mara Brubaker, bearing the initials “M. B.” and the year “1774.”87

This description matches an egg that survives today as part of the collection of the Pennsylvania Folklife Society, now at the Berman Museum, Ursinus College. It is likely that Shoemaker’s discovery in the Herald was connected in some way with his obtaining the egg for the Society. Interestingly, recent photographs of the object suggest that this artifact appears to have been created using a resist dye technique, rather than scratching, which is an unexplainable anomaly in Pennsylvania Dutch Easter egg traditions. Evidence for this lies in the uniformity of smooth wide lines and round dots in the creation of floral designs, a central crown motif, and the initials in two hearts, surrounded by dots—all of which were likely produced by applying wax with a tool.88

Although Brubaker vouched for the provenance of the egg as being connected with a family member in the Lancaster County Mennonite community, the wax resist technique appears more consistent with European techniques than those of early Pennsylvania. Alfred Shoemaker warns later in Eastertide in Pennsylvania that he questions the Pennsylvania provenance attached to “a considerable amount of folk art today in museums and private collections dubbed as Pennsylvania Dutch,”89 citing a Swiss imported egg as evidence of transatlantic exchange of material culture in the twentieth century by travelers and collectors.90

Two scratched Easter eggs by Peter V. Fritsch, 2007 and 2002, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, gift of Peter V. Fritsch. These elaborate Easter eggs were produced as gifts for Peter Fritsch’s mother, to whom he presented an egg every year as a token of his appreciation and affection. Many of Fritsch’s close relatives and friends received eggs each year, carefully inscribed in a variety of scratched and painted techniques.

Shoemaker also cites what he describes as the earliest known reference to a scratched egg “in the Dutch Country” from Thomas Anburey’s Travels Through the Interior Parts of America, published in London in 1798. However, Anburey’s description of scratched eggs was not from Pennsylvania as Shoemaker reported, but rather in Frederick, Maryland, where a sizeable population of Pennsylvania Dutch families had relocated from Lancaster, York, and other counties adjacent to the Mason-Dixon line dividing the two states. In a letter from “Colonel Beattie’[sic] Plantation, near Frederick Town, in Maryland, July 11, 1781,” Anburey explains:

“At Easter holidays the young people have a custom, in this province, of boiling eggs in logwood, which dyes the shell crimson, and though this colour will not rub off, you may, with a pin, scratch on them any figure or device you think proper. This is practised by the young men and maidens, who present them to each other as love tokens. As these eggs are boiled a considerable time to take the dye, the shell acquires great strength, and the little children divert themselves by striking the eggs against each other, and that which breaks becomes the property of him whose egg remains whole.

To impress the minds of his children with their glorious struggle for independence, as they term it, the Colonel [Beattie] has an egg, on which is engraved the battle of Bunker’s Hill. This he takes infinite pains to explain to his children, but will not suffer them to touch it, being the performance of his son gone to camp; but now being slain, he preserves it as a relic.”91

Anburey’s personal account provides an interesting overview of the tradition of scratched eggs, although he does not mention the strong German cultural influence in Frederick, Maryland. It is noteworthy that Colonel Charles Beatty (1730–1804) whose paternal line was Irish and originally hailed from Ulster County, New York,92 showed such enthusiasm for the local tradition. But Anburey makes no mention of the tradition’s origin within any particular ethnic enclave, suggesting that the tradition had already become a shared regional tradition by this time—one that all Americans could enjoy.

Scratched Easter egg as a token of affection, Pennsylvania, 1920, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. In 1920, an anonymous admirer in Pennsylvania scratched this Easter egg as a token of affection for “Miss Betty.” The egg features images of stars, a large white heart, and an anchor, symbolizing devotion and steadfastness. The golden-brown color likely resulted from using onion skins or black walnut shells as dye materials.

Tokens of Affection, Friendship, and Devotion

Most notable in Anburey’s letter is the description of the eggs as “love tokens.” Among the historic eggs to survive to the present day, very few show obvious indications of having been tokens of affection, although it is clear that the practice was common. Shoemaker documented one example from 1888, bearing nothing more than a heart, the year, and the name “Lizzy Cammauf.”93 This was likely Lizzy E. (Peiffer) Cammauf (1870–1935), of Sinking Spring, Berks County. The egg bears her married name when she was 18 years old, suggesting that the egg may have been the work of her husband, George F. Cammauf (1867–1942).94 On another example from 1920, an anonymous admirer inscribed the name of his sweetheart “Miss Betty” as well as elaborate images of stars, a large white heart, and an anchor. Thoughtfully, the symbols appear to suggest devotion and steadfastness, and the golden brown color of the shell was likely produced with onion skins or black walnut shells.95

Pennsylvania Dutch Easter eggs by Peter V. Fritsch, Longswamp, Berks County, ca. 1975–2010, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, gift of Peter V. Fritsch. The prolific Pennsylvania Dutch artist and poet Peter V. Fritsch (1945–2015) created these Easter eggs as part of his annual tradition of handcrafting tokens of appreciation for his friends and family. Rooted in both traditional and contemporary artistic expressions, Fritsch’s work evokes the connection of local culture with the land and the cycles of the seasons. His work features depictions of birds, plants, and creatures of the earth, along with geometric motifs inspired by stars and religious symbols. Using a variety of scratched and painted techniques, Fritsch’s work embodied both the continuity and evolution of Pennsylvania Dutch Easter egg traditions.

This tradition of giving eggs to loved ones, friends, and family continues to this day in the Pennsylvania Dutch cultural region. In Berks County, one of the most prolific makers of scratched eggs in the late twentieth century was Peter V. Fritsch (1945–2015) of Longswamp Township, Berks County. A Pennsylvania Dutch-language poet, artist, musician, playwright, and an art teacher in Reading public schools, Fritsch produced dozens of exquisitely scratched and painted eggs each year and presented them as gifts to his friends and family. While living on an ancestral farm along South Mountain in Longswamp, Fritsch raised his own chickens, ducks, geese, and peacocks, and even ventured to local ponds and lakes to bravely gather eggs from the nests of Canada geese, armed with nothing more than a household broom and an oak splint basket.96

Bird tree Easter egg, Peter V. Fritsch, Longswamp, Berks County, 2002, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. The Tree of Life, teeming with birds, is an important religious symbol of life and rebirth for the Pennsylvania Dutch. This egg by Peter V. Fritsch features an original Pennsylvania Dutch poem on the reverse side.

Rooted in traditional and contemporary artistic expressions, Fritsch’s work evoked the connection of local culture to the land and the progression of the seasons, with special attention paid to the birds, plants and creatures of the earth, along with geometric motifs of the stars and religious symbols. Using a variety of scratched and painted techniques, Fritsch’s work embodies both the continuity and evolution of Pennsylvania Dutch Easter egg traditions.

One of Fritsch’s most cherished motifs was the “bird tree”—a variation of the Pennsylvania Dutch Tree of Life, and a central folk-cultural religious symbol of life and rebirth among the Pennsylvania Dutch. One particularly elaborate example of Fritsch’s work preserved in the collection of the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University, depicts the Tree of Life positively teeming with colorful songbirds, accompanied by an original Pennsylvania Dutch-language poem on the reverse: “Kinner nau sehn die Vegel im Bahm. Im Friehyaahr sie singe paar bei paar, Aasech Gottes schaffes in Auge un Ohr” (Children, now see the birds in the trees. Their singing in springtime is a sign of God’s work to the eye and ear).

Although the Pennsylvania Dutch folk art depiction of the Tree of Life is frequently misconstrued as an expression of commercialized kitsch or part of a polite, secular form of decoration, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Like many of the classic religious motifs featuring images of the natural world and celestial bodies, the Tree of Life is not only biblical, but also emblematic of the tendency in Protestant devotional art to celebrate the natural world as an expression of the sacred.

Tree of Life, birth and baptismal certificate, Walker Township, Centre County, 1813, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. This colorful manuscript certificate features the Tree of Life. In the devotional traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch, this symbol reflects their religious appreciation for the natural world. The Tree of Life motifs have stylized branches and birds arranged symmetrically around the form of a horn—a symbol of annunciation—as the trunk. The central inscription records the baptism of Moses Dunckel, son of Jacob and Lowis (Krebs) Dunckel, on April 14, 1813. Manuscript artists, who were often community schoolteachers, regularly created these certificates for Pennsylvania Dutch families.

Among early works of art of the Pennsylvania Dutch, the Tree of Life appears especially in illuminated religious documents, including birth and baptismal certificates, religious verses used for copy exercises in early schools, and inscribed bookplates in prayerbooks presented to youth at confirmation. One particularly colorful manuscript certificate, featuring vibrant images of the Tree of Life, commemorates the baptism of Moses Dunckel, born just two weeks after Easter on April 14, 1813, to Jacob and Lowis (Krebs) Dunckel of Walker Township, Centre County. Produced by an anonymous scrivener and artist in that region known for producing arrangements of birds, the certificate bears characteristic symmetrical arrangements of stylized branches and birds. These Tree of Life motifs feature the form of a horn—a symbol of annunciation—as the trunk.

Tree of Life, Johnny Claypoole, Lenhartsville, Berks County, 1977, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. While the folk-art portrayal of the Pennsylvania Dutch Tree of Life is sometimes dismissed as kitsch or merely a polite, secular form of decoration, this interpretation is misleading. Similar to other classic motifs that incorporate depictions of the natural world and celestial bodies, the Tree of Life not only holds biblical significance but also exemplifies a tendency in Protestant devotional art traditions to celebrate the natural world as an expression of the sacred.

Such certificates were commonly produced for Pennsylvania Dutch families by manuscript artists and calligraphers, who were often schoolteachers in their communities, and these material texts are commonly known today as Fraktur, after the German-language term for the elaborate blackletter calligraphy (Frakturschrift).97 Occasionally, these were the very same artists who decorated Easter eggs,98 and in one such case, a Pennsylvania Dutch scrivener produced the earliest known images of the Easter rabbit in North America.99

The Easter Rabbit

Sometime between 1795 and 1810, school master, church warden, and calligrapher Johann Conrad Gilbert (1734–1812) of Brunswick Township, Schuylkill County,100 produced a series of carefully drawn and painted images of the Easter rabbit as Belohnungen or rewards of merit for his school students.101 As a first generation emigrant from Germany, Gilbert’s depiction of the Easter rabbit, characterized with a wild posture, bristling ears, and unfurled tongue, reflects the original meaning of the German term Osterhase as “Easter hare.”102 Gilbert’s wild hare carries a low-slung basket replete with colored Easter eggs in red, yellow, green, and black, representing his legendary role as the conveyor of eggs to children on Easter morning. Thus, the very notion of the “Easter rabbit” is an American idiom, translated from the Pennsylvania Dutch vernacular term Oschderhaas, and predicated on the fact that the German-speaking immigrants found no hares when they settled in Pennsylvania.103 Two of Conrad Gilbert’s Easter rabbit paintings managed to survive into the present day, and both are preserved in institutional collections at Colonial Williamsburg and Winterthur Museum.104

Easter rabbit, after Conrad Gilbert, ca. 1810, theorem painting on velvet by Sandra Jean Coldren, private collection of Elaine Vardjan, Oley, Berks County. Schuylkill County schoolmaster Conrad Gilbert’s Easter rabbit images, the earliest in America, continue to inspire artists in Pennsylvania to embrace the roots of this custom. Here Sandra Jean Coldren faithfully recreates Gilbert’s original paintings, depicting the Easter hare with a basket of colored eggs. Two of Gilbert’s paintings survive, which he made as rewards of merit for his students when he taught in a one-room school in present-day Orwigsburg, Schuylkill County.

Conrad Gilbert house blessing, Tulpehocken, Berks County, 1784, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University Johann Conrad Gilbert (1743–1812) penned this hand-written house blessing titled “A Beautiful Christian House Blessing for All Pious House Fathers and House Mothers” (Ein schöner Christlicher Hauß segen, für alle fromme Hauß väter und Hauß mütter). It was created for the family of Adam Schmidt of Tulpehocken Township, Berks County. The blessing provides comforting words of advice for Pennsylvania Dutch households, meant to be displayed and read aloud during special occasions, such as Easter Day, and in times of trouble.

German-speaking immigrants like Conrad Gilbert, who arrived in Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century, first introduced the Easter rabbit to North America. Although they emigrated from many different parts of what is today Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Alsace, France, the majority came from communities in the Southwest in an area formerly defined as the Kurpfalz, or the Electoral Palatinate where the tradition of the Easter rabbit was widely known.105 This included the region that is now the Rhineland-Pfalz of today, as well as parts of present-day Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, and Alsace. Emigrants from territories farther south or east departed by means of the Rhine River that passed through the Palatinate, making the region a diverse cultural mixture throughout the time of emigration. Interestingly, there were once other legendary animals that delivered Easter eggs in German-speaking lands, such as the Easter fox of Westphalia, the cuckoo of Styria, the Easter stork of Thuringia, as well as many others,106 that never found their way to Pennsylvania.

Easter rabbit watercolor illustration, Peter V. Fritsch, Longswamp, Berks County, 2009, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University, gift of Peter V. Fritsch. In this watercolor painting, Peter V. Fritsch depicts a naturalistic Easter rabbit carrying eggs in a woven basket to children on Easter morning. The title in Pennsylvania Dutch reads: “Der Oschder Haas kummt mit die Oier!” (The Easter rabbit comes bearing the eggs!). Fritsch was also a bringer of eggs, creating elaborately decorated chicken, goose, and peacock eggs each year for friends and family.

According to the regional custom, early Pennsylvania Dutch families often prepared Easter baskets or nests for the arrival of the Oschderhaas, who, as children were told, would visit in the night to fill the baskets or nests with decorated eggs. Children were encouraged to create these nests outside in the open air, or on windows or on the floor in the home. They carefully considered the choice of soft nest materials, and locations accessible to the Easter rabbit. These nests were once commonly created each year by children of farm families, but due to their ephemeral nature, no original examples are known to survive.

Pennsylvania Dutch traditional Easter basket, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. Pennsylvania Dutch families were the first Americans to create Easter baskets. Children decorated household baskets and lined them with straw or dried meadow grass. This split-oak gathering basket, complete with a sturdy handle, was ideal for Easter egg hunts.

Hand-built straw Easter nest, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University. A parallel to the Easter basket tradition is the creation of Easter nests by children who expected overnight visits from the Easter rabbit. These nests were made outdoors, on windows, or on the floor in the home. Children thoughtfully chose soft nest materials and accessible locations for the Easter rabbit. Once a common practice among children in farm communities, the temporary nature of these nests has resulted in the absence of surviving examples.

The Easter rabbit was also believed to lay these colored eggs, and was credited with hiding hard boiled, dyed eggs throughout the property for the children to gather in their baskets. Another surprising (and biologically puzzling) aspect of the legend, is that many Pennsylvania Dutch people refer to the egg-laying Easter rabbit as “he”—the result of generations of use of the masculine pronoun der accompanying the vernacular word Haas.107 Although the pronoun applied to the whole species and not any one particular individual rabbit, the result is that even today throughout the United States, many communities interpret the Easter rabbit as male—further evidence of the tradition’s origin.

The legend of the Easter rabbit was completely unknown to the English, Scotch-Irish, and Welsh immigrants in the Commonwealth, as well as the other communities of Anglo-Americans who settled throughout the United States. Nevertheless, the tradition soon spread and was widely embraced by diverse communities by the second half of the nineteenth century. Today, the Easter rabbit has become one of the most cherished of American holiday traditions.

In 1882, prolific writer, educator, and Quaker Phoebe Earle Gibbons (1821–1893) of Lancaster, described the rural practices of children in Southeastern Pennsylvania:

“If the children have no garden, they make nests in the wood-shed, barn, or house. They gather colored flowers for the rabbit to eat, that it may lay colored eggs. If there be a garden, the eggs are hidden singly in the green grass, box-wood, or elsewhere. On Easter Sunday morning they whistle for the rabbit, and the children imagine that they see him jump the fence. After church, on Easter Sunday morning, they hunt the eggs, and in the afternoon the boys go out in the meadows and crack eggs or play with them like marbles. Or sometimes children are invited to a neighbor’s to hunt eggs.”108

Dr. Alfred L. Shoemaker emphatically described the Easter rabbit as “perhaps the greatest contribution the Pennsylvania Dutch have made to American life.”109 Not one to favor over-use of the superlative, Shoemaker’s reasoning was simple—no other aspect of Pennsylvania Dutch culture achieved such broad acceptance in communities throughout the United States. However, Shoemaker also concedes that the tradition was certainly reinforced by later waves of nineteenth- and twentieth-century immigrants to the United States, as well as the mass production of Easter trade cards imported directly from Germany.

Over four million German immigrants arrived between 1850 and 1900, and populated cities in the Northeast and Midwestern United States,110 such as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Chicago. These new groups of German-Americans were culturally distinct from the earlier communities of the Pennsylvania Dutch, who were predominantly rural, and increasingly relied on English as their educational language, while Pennsylvania Dutch vernacular remained their oral, home language. Both groups, however, contributed to perpetuating the Easter rabbit as an American tradition.

Egg-shaped Easter rabbit candy holders, Germany, ca. 1900, private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal. These candy holders feature classic images of the Easter rabbit in his traditional role as the bringer of eggs amidst symbols of spring such as pussy willows and hatching chicks. The candy holders were mass produced in Germany and imported to the United States. These candy holders were first printed as flat, full-color lithographs that were carefully sliced and adhered in strips to the convex surface of pressed paper egg-forms. Although chocolate was also a major export from Germany, these candy holders typically were filled by confectioners in urban areas of the United States who sold them directly to customers. The candy holders were not only containers for Easter candy, but they also served as decorations that could be reused year after year. The simplest way to display them is to suspend them from a loop of string inserted between the two halves of the egg.

German papier mâché Easter rabbit candy holder, Marolin Manufaktur, Steinach, Germany, private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal, Bryn Athyn, Montgomery County. This papier mâché candy holder was made by the German company Marolin, established in 1900. Marolin is known for producing finely cast Nativity figures, holiday decorations, and toys. The company specializes in hollow candy holders, including traditional Easter rabbit forms. The company’s unique papier mâché formula was nearly lost after World War II when the GDR in East Germany banned the promotion of religious figures. However, during German reunification in 1990, the family company resumed private operations. The original recipe, barely legible, was unexpectedly rediscovered on the back of a cellar door, allowing Marolin to resume its tradition.

German Osteroier

With the rise of industrial printing in the second half of the nineteenth century, lithographic Easter ephemera was mass produced on a commercial scale in Germany, and to a lesser extent in the United States. Die-cut and embossed lithograph prints were issued as trade cards and formed into papier mâché egg-shaped candy holders presented to children at Easter. These lithographic artistic works often featured scenes of the Easter rabbit or groups of rabbits hiding and delivering eggs, or images of the natural world at springtime, complete with floral bouquets, nests of eggs, and baby ducks and chicks, often accompanied by highly sentimentalized portrayals of children with a distinctly Victorian style. Although the First World War later stopped the import of these candy holders to the United States, production continued after the war, replacing the imagery of the Victorian era with cartoon depictions of Easter that only served to increase the popularity of the candy holders well into the twentieth century.

This transatlantic holiday exchange halted by the time of the Second World War, and international trade in traditional holiday decorations all but collapsed. Christian traditions also faltered under pressure from the Nazi regime, and again later when East Germany was divided and under Soviet control. Although German companies were among the most productive purveyors of Christian and secular holiday decorations in the world, many were forced to repurpose their businesses under communist leadership. One such company, Marolin Manufaktur of Steinach, had been established in 1900 by Richard Mahr (1876–1952), who specialized in producing religious figures in the Nazarene style popular in the late nineteenth century from finely cast papier mâché. By the 1920s, Marolin had expanded beyond a family company to include a wider range of production, including Nativities, glass Christmas ornaments, Easter figures, and candy holders. At the peak of the company’s production, the Second World War halted the production of nativity figures under the Third Reich, and following the war, religious holiday figures and decorations were prohibited under the Soviet-affiliated German Democratic Republic. The company continued to make cast children’s toys, but it was not until after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and German reunification in 1990 that the company was finally allowed to once again resume production of traditional cast papier mâché figures. But the company suffered tremendous loss of infrastructure with the destruction of its original molds and equipment. Even the original recipe for the papier mâché was forgotten until a barely legible transcription of the recipe written in chalk on the back of a cellar door was unexpectedly re-discovered, allowing the family company to resume production of traditional wares. Today the Marolin company continues to produce cast Easter rabbit candy holders of exceptional quality.111

Two Victorian candy holders, Germany, ca. 1900, private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal. These classic Victorian illustrations show a child gathering Easter eggs from the Easter rabbit, accompanied by images of rabbits and chicks. Employing mass production methods, the images were printed and applied to pressed paper candy holders. After cutting the lithograph prints into strips, they were carefully adhered to the round surface of the egg. This technique preceded the use of steam-operated presses that shaped printed images into convex egg forms for the two halves of the candy holders. Typically filled with chocolate, these holders were subsequently exported to the United States.

Right: Postcard of Easter rabbit delivering eggs with a cannon, Germany, ca. 1910, private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal. This German postcard shows a uniformed Easter rabbit with chickens, blasting Easter eggs from a cannon toward a rural town in the distance. This humorous take on the Easter rabbit legend was printed in full-color lithography with metallic leaf and embossed, giving it a three-dimensional effect. Clever and inventive Easter greetings like these, printed in Germany, were widely popular in the United States before the First World War.

Left: Greeting card with Easter rabbit posing for the camera, Germany, ca. 1910, private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal. This tongue-in-cheek greeting card features an Easter rabbit posing for the camera. It belongs to a genre of humorous Easter lithographs mass produced in Germany and distributed in Europe and the United States. The English caption “Easter Greetings” confirms that this card was intended to delight American audiences with its imaginative subject.

Although German Easter egg traditions were among the first to be brought to Pennsylvania, the traditions also evolved considerably over the centuries following mass immigration to North America, and Germans embraced a wide range of styles and forms, including scratched and painted eggs; rush pith, rye-straw, and fabric appliqué, as well as wax-resist dye methods and acid etching, both of the latter creating exceptionally fine line work.112 These artistic eggs are still customarily given as gifts and tokens of affection, and the traditions have continued to grow and evolve on both sides of the Atlantic.

Easter greeting card, S. Hildesheimer & Co., private collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer. During the late nineteenth century, Victorian greeting cards featuring Eastertide holiday imagery became widespread in the United States and Europe. Advances in full-color lithographic printing enabled mass production, like this eight-page lace-bordered card by British publisher Siegmund Hildesheimer (1832–1896) of London and Manchester. Born in Halberstadt, Germany, Hildesheimer’s works reached the English-speaking world and were popular among Pennsylvania Dutch families. This card was displayed in the home of Alexander and Susan Printz of Reading, Pennsylvania, and later in the home of their daughter, Laura May (Printz) Green of Lebanon.

One of the leading producers of Easter eggs in Europe is the Peter T. Priess Company of Vienna, Austria, which employs 100 artists in nearby Salzburg to produce a line of painted Easter eggs. The company was established in 1975 by Peter and Dorota Priess, specializing in traditional glass Christmas ornaments and Easter eggs made from the shells of chicken, turkey, goose, and ostrich eggs that have been carefully blown out and outfitted with ribbons for hanging. They specialize in a wide variety of traditional painted drop-and-pull geometric designs, as well as images of Easter rabbits, chicks, and other springtime themes. The company provides the yolks and whites of the eggs to bakeries as a sustainable partnership.113 The Priess company is a leading exporter of eggs to other parts of the world, and because their eggs are meant to be hung, they have greatly facilitated the continued tradition of the Osterbaum (Easter tree) in Germany.

Cotton-wrapped walnut tree, featuring eggs by Peter Priess Company of Vienna and Salzburg, ca. 2000, and sawdust dolls of rabbits and chicks by Debbie Jarret, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University and private collection of Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal.

The Osterbaum and the Egg Tree