Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2024

This limestone funerary stela, belonging to a man named Bebi and dating to the First Intermediate Period (2150–1980 BCE), is one of eight ancient Egyptian objects recently loaned to Glencairn Museum by the Penn Museum.

As part of updates in the Egyptian gallery, Glencairn Museum recently welcomed a loan of eight ancient Egyptian artifacts from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum) in Philadelphia. These objects complement Glencairn Museum’s permanent collection and are displayed within a chronological framework in the Egyptian gallery.

Why would Glencairn Museum borrow material from another institution when it already has its own Egyptian collection? It is common practice for museums to lend and borrow objects for special exhibitions, short-term loans, and long-term displays. Glencairn Museum has a longstanding relationship with the Penn Museum, having previously borrowed objects from them and loaned items in return. Nearly 100 years ago, the Penn Museum borrowed a renowned marble statue of the goddess Minerva-Victoria from Cyrene, originally collected by Raymond Pitcairn. This statue was exhibited at the Penn Museum from 1935 to 1986, after which it returned to Glencairn Museum and is now displayed in the Roman Gallery (Figure 1). For more information on this statue, see this 2014 issue of Glencairn Museum News. Currently, a loan of jewelry from Glencairn Museum’s collection is on display in the Penn Museum’s Roman gallery along with jewelry from Penn’s own collection (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Marble statue of the Roman goddess Minerva-Victoria. Dating to the 2nd century CE from Cyrene, Glencairn Museum, 09.SP.1629.

Figure 2. Some of the jewelry on loan from Glencairn Museum can be seen here in the Penn Museum’s Roman Gallery. The necklaces visible in the close-up view are 15.JW.159, 15.JW.194 and 15.JW.170.

In late 2022, a loan of eight Egyptian objects that had been on display in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery since 1984 was returned to the Penn Museum. These objects included several vessels, a limestone offering basin (Figure 3), a terracotta soul house (Figure 4), and a painted limestone funerary stela (Figure 5). Following the return of these items, Glencairn Museum’s curator approached the Penn Museum to request a new selection of objects to take their place. This group of artifacts will likely remain on display for the next several years. This brief article will introduce you to the newest additions to Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery and situate them within their chronological and cultural contexts.

Figure 3. Liquid offerings were an essential part of Egyptian cult practices, both in tomb and temple settings. Basins for liquid offerings have been found in Old Kingdom (2625–2130 BCE) tombs. Limestone basin of a woman named Persenet from Giza, Old Kingdom, 2625–2130 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E13526).

Figure 4. Providing a tomb—a house for eternity—was an important part of Egyptian funerary practice. During the Middle Kingdom, graves of poorer individuals were sometimes marked with ceramic model houses. This magically provided for the deceased who could not afford to build a tomb. Terracotta soul house from Rifeh, Middle Kingdom, 1980–1630 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E2942A).

Figure 5. This crudely made funerary stela is for a man named Kemsi, who had the title “Administrator of the Ruler’s Table.” It was made for him by his brother, a man named Neferhotep, who had the title of judge. This stela is from Abydos, Second Intermediate Period, 1630–1539 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E9182).

A History of Collaboration

Glencairn Museum has maintained a close relationship with faculty, researchers, and graduate students at the Penn Museum and the University of Pennsylvania for many years. For instance, Dr. Irene Romano and Dr. David Gilman Romano, who are now at the University of Arizona, were long associated with both the Penn Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. In 1999, after researching Glencairn Museum’s Greek and Roman collections, they published the book, Catalogue of the Classical Collections of the Glencairn Museum.

In the early 1980s, David Pendlebury, then a graduate student in Egyptology at the University of Pennsylvania, was hired to catalogue Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian collection. During the process, he became interested in the Old Kingdom false door of Tepemankh (Figure 6). His research revealed that the elements of Tepemankh’s false door in Glencairn Museum’s collection matched with an additional piece of Tepemankh’s door housed at the Louvre in Paris (Figure 7). Further elements of the false door are in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark (Figure 8). (For more information about Tepemankh’s false door, see this 2011 issue of Glencairn Museum News.) Pendlebury went on to participate in fieldwork at the site of Giza as a member of the Giza Mastabas Project. During the excavations, additional objects relating to the tomb of Tepemankh were recovered, and the team produced a complete photographic and epigraphic record of the remains of the tomb in situ (Figures 9, 10).

Figure 6. View of the false door of Tepemankh in the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn Museum (E1150). Dating to the Fifth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (circa 2500–2350 BCE), the mastaba of Tepemankh was located at Giza. Tepemankh was an important official who was a royal acquaintance, an overseer of the department of palace attendants of the Great House, and a priest in the cult of King Khufu.

Figure 7. Limestone relief from the tomb of Tepemankh in the Louvre, Paris (E25408). Image courtesy of the Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités égyptiennes.

Figure 8. Line drawing of the false door of Tepemankh showing the joins between the pieces in Glencairn Museum, the Louvre, and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (AEIN 1438). (Image after a figure in Giza: Am Fuss Der Grossen Pyramiden: Katalog Zur Sonderausstellung.) The image to the left shows the plan of Tepemankh’s tomb chapel. The location of the false door is marked with a blue star.

Figure 9. Members of the Giza Mastabas Project in August of 1982. Seen from left to right are Edward Brovarski, David Pendlebury, William Kelly Simpson (standing), unidentified, Lynn Holden, and Carter Wentworth (image courtesy of Giza Project at Harvard University).

Figure 10. Lynn Holden and David Pendlebury in the re-excavated chapel of Tepemankh (D20) at Giza (image courtesy of Giza Project at Harvard University).

Figure 11. Glencairn Museum curator Ed Gyllenhaal doing epigraphy in the tomb of Ihy in Saqqara, Egypt, in the 1990s (photo by author).

Glencairn Museum’s current curator, Ed Gyllenhaal, is also a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, where he received his M.A. in Egyptology from the Department of Oriental Studies (now the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures). Gyllenhaal took part in three Penn Museum expeditions to Egypt, working at the sites of Deir el-Bersheh and Saqqara as an epigrapher. In this role, he was responsible for copying and documenting the decoration and inscriptions on the walls of tombs dating to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (1980–1630 BCE; Figure 11).

The New Loan

Let us now take a closer look at the objects included in the new loan on display in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery. These artifacts encompass a variety of types, including stelae, ceramic vessels, figurines, and funerary objects. Originating from various sites across Egypt, they cover a broad chronological range from the Predynastic Period to the New Kingdom.

Stelae

Many of the essential elements of Egyptian civilization crystalized during the Early Dynastic Period (Dynasties 1–3, 3000–2625 BCE). The use of tomb stelae inscribed with a person’s name began during this period. Among the objects on loan is a small, unassuming, round-topped limestone stela from the site of Umm el Qa’ab at Abydos, an important ceremonial site for both royal and private individuals. Abydos later became known as the burial place of the god Osiris, king of the underworld (Figure 12). Several tombs of First Dynasty kings at the site of Abydos (Figure 13) include burials of court officials and servants who were sacrificed and buried alongside the ruler. For instance, over three hundred subsidiary burials surrounded the tomb of King Djer. This practice of human sacrifice ended after the First Dynasty. Each of these graves, like the royal tombs they accompanied, was marked by a round-topped stela. The royal stelae are carved of hard stone with well-carved decoration (Figure 14).

Figure 12. Figurine of Osiris, king of the underworld, Glencairn Museum, E74.

Figure 13. View of Umm el Qa’ab, Abydos, the location of the royal tombs of Egypt’s earliest rulers. The name Umm el Qa’ab means “Mother of Pots” in Arabic, and refers to the copious amount of pottery left as offerings by pilgrims to the site (photo courtesy of Ayman Damarany).

Figure 14. Funerary stela of King Qa’a from Umm el Qa’ab, Abydos, First Dynasty, 3000–2800 BCE. This stela is one of a pair that marked the king’s tomb. It is carved of basalt, a hard stone, in contrast to the soft limestone used for the stelae that marked the graves of the subsidiary burials (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E6878).

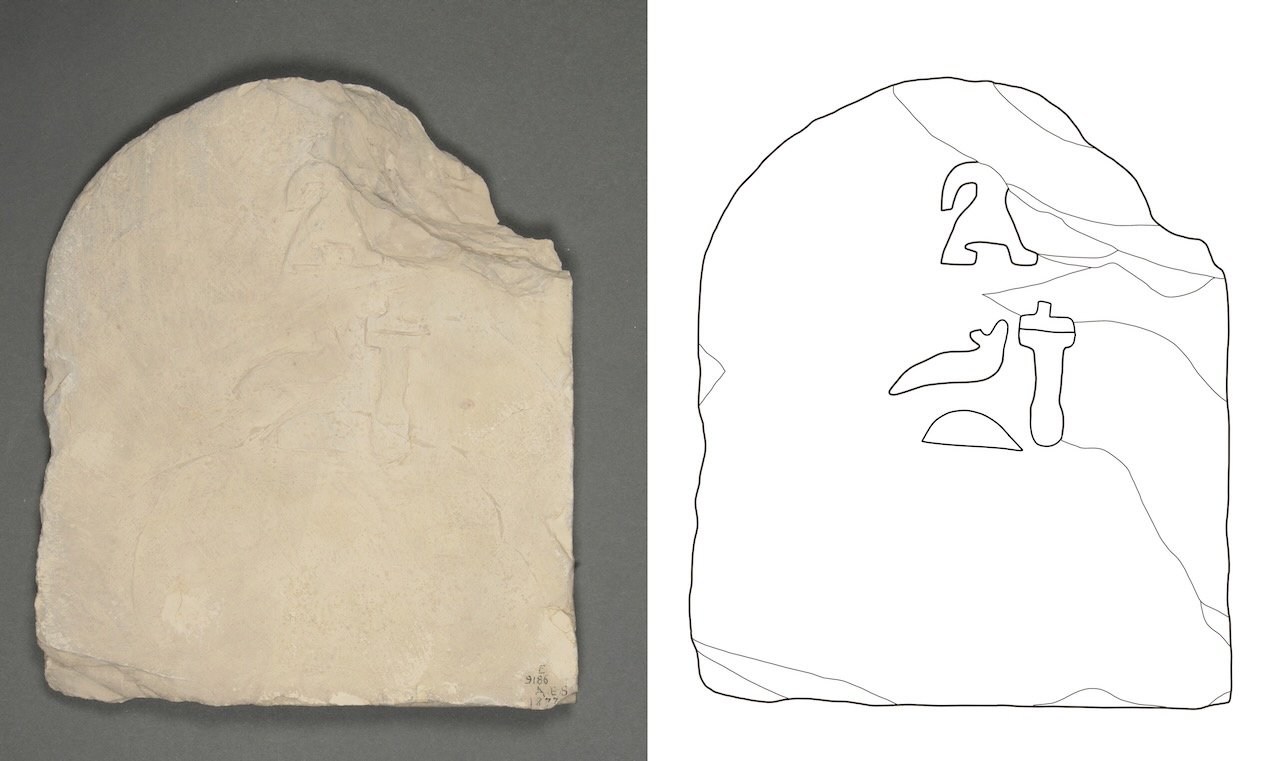

The stelae of the kings’ retainers are small and made of somewhat crudely carved limestone. The hieroglyphs on the stela now on loan to Glencairn Museum (Figure 15) spell out the name of its owner, Nefer (or possibly, the feminine version, Nefret), meaning “Good” or “Beautiful.” This individual was buried near the tomb of King Semerkhet and analysis of their skeletal remains suggests they had a form of dwarfism. This stela was excavated at Abydos by W. M. Flinders Petrie in 1899–1900.

Figure 15. Limestone funerary stela of Nefer from Abydos, Early Dynastic Period, First Dynasty, 3000–2800 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E9186).

As royal authority waned at the end of the Old Kingdom (2625–2130 BCE), local governors, known as nomarchs, grew more influential. Egypt fragmented into competing dynasties—one in Heracleopolis and another in Thebes. This period saw civil strife, famine, and a heightened role for these nomarchs, who claimed they could better care for and protect their local populations. Some of this instability may be reflected in the art, as the royal workshops no longer had influence over the entire country. Disruptions in trade affected the quality of funerary goods, leading even the wealthy to use local materials for their coffins.

Dendereh was an important ancient Egyptian site that spanned from the Predynastic Period to the Greco-Roman Period. From 1915 to 1918, Penn archaeologist Clarence Fisher (Figure 16) conducted several excavation seasons there, uncovering thousands of artifacts in the cemetery where provincial nobles from the First Intermediate Period (2150–1980 BCE) were buried. These officials were buried in large mastaba-type tombs, which featured stelae on their eastern sides. A mastaba, first seen during the Old Kingdom, is a type of tomb named after the Arabic word for “bench,” due to its rectangular shape, slightly sloping sides, and flat top. A deep shaft beneath the mastaba led to the burial chamber, which contained typical tomb goods such as wooden coffins, jewelry, stone and ceramic vessels, and metal objects like mirrors, tools, and weapons.

Figure 16. Penn Museum archaeologist Clarence Fisher (1876–1941) seen excavating at the site of Dendereh (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, #38942).

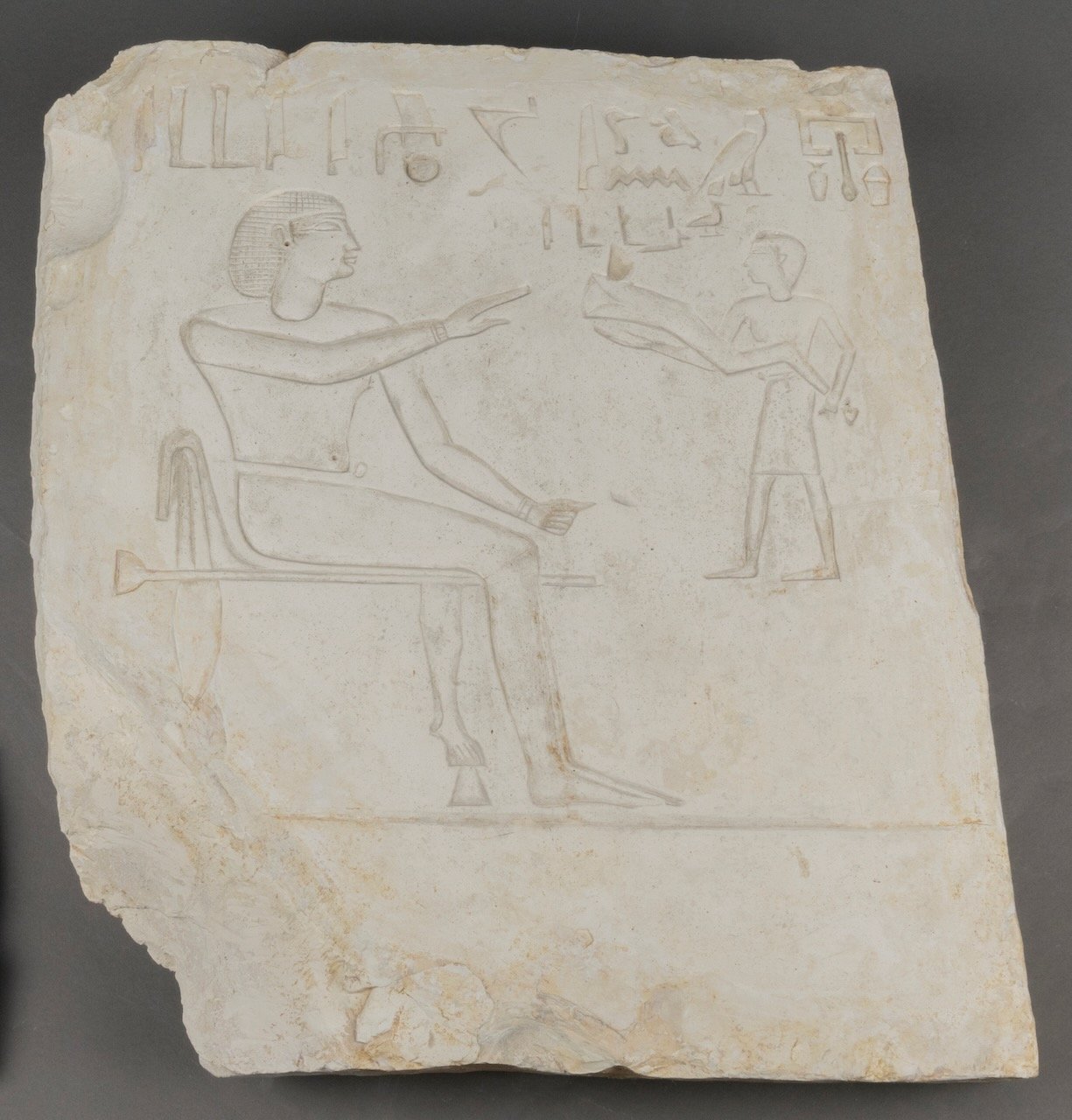

Funerary stelae from this period typically show the deceased with family members and included images of offerings of food and drink. They were inscribed with funerary prayers and the name and titles of the tomb owner. This stela (Figure 17), now on loan to Glencairn Museum, honors a man named Bebi. It displays hieroglyphs at the top reading, “Invocation offerings of meat and fowl for the revered one, Bebi.” Smaller hieroglyphs below show a figure holding a haunch of beef, labeled as “his son, Bebi.” The son’s small size in the depiction is not indicative of his actual height but is a stylistic feature of ancient Egyptian art, where more significant figures are portrayed on a larger scale.

Figure 17. Limestone funerary stela belonging to a man named Bebi from Dendereh, First Intermediate Period, 2150–1980 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, 29-66-668).

Ceramics

The origins of Egyptian civilization appeared during the Predynastic Period, a long and dynamic era which spanned around 2000 years. Prior to the invention of writing, and before the country was united under a single ruler, the peoples of the Predynastic Period created social, cultural, and religious practices that became hallmarks of the following Pharaonic era. The archaeological record of the Predynastic is fragmentary, but evidence from cemeteries and settlement sites gives insight into the lives of these early residents of the Nile Valley. One class of artifacts that offers insight into this early period of Egyptian prehistory are ceramic vessels.

Figure 18. Painted lug-handled jar, from Naqada or Ballas, Egypt, Predynastic Period, Naqada II-III, 3500–3000 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E1391).

Pottery vessels were an essential part of Egyptian life. They were used by all social classes for the consumption of food and drink and the storing and shipping of commodities. All ceramics are made of clay and fired at high temperatures. The type of clay and different surface treatments result in a variety of appearances. By examining the changes in pottery forms, design, and manufacture, archaeologists can assign dates to ceramics.

During Egypt’s Predynastic Period, people were buried in shallow graves in the sand, without the elaborate burial chambers or above-ground tomb chapels seen in later periods. Nevertheless, the items they were buried with indicate a belief in the afterlife. Pottery vessels, mainly for holding food and drink, were the most common grave goods. Throughout certain phases of the Predynastic Period, artisans adorned these vessels with diverse decorations, including figural designs depicting the natural landscape, animals, or human figures, while others featured more abstract or schematic patterns.

The painted decoration on one of the jars loaned by the Penn Museum may depict basketry (Figure 18). Sometimes ancient Egyptian artists chose to represent organic materials in more permanent mediums. The other painted vessel (Figure 19) is decorated to imitate stone, which was more expensive and difficult to craft. These vessels were both excavated by Flinders Petrie in the late 1890s and came from the sites of Naqada or Ballas, two locations with extensive Predynastic cemeteries.

Figure 19. Painted lug-handled jar, from Naqada or Ballas, Egypt, Predynastic Period, Naqada II-III, 3500–3000 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E1442).

Faience Baboon

The Upper Egyptian site of Hierakonpolis was home to an early temple dedicated to Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship. Excavations conducted by the archaeologist J. E. Quibell in 1898 uncovered a significant cache of ritually buried votive objects, including the famous Narmer Palette (Figure 20). This deposit also contained ivory and faience figures depicting humans and animals. Among them was a figurine, now on loan from the Penn Museum, of a seated baboon (Figure 21; Early Dynastic Period, Dynasty 1, 3000–2625 BCE). It represents the moon god Hedj-wer, whose name means the “Great White One.” Hedj-wer was a solar deity.

Figure 20. The Narmer Palette was found at the site of Hierakonpolis. This ceremonial object commemorates the unification of Egypt under one ruler.

Figure 21. Faience figurine of a seated baboon from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Early Dynastic Period, Dynasty 1 3000–2625 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E3843).

Figure 22. An amulet representing the god Thoth as an ibis-headed man, Glencairn Museum, E219.

Baboons were often linked with the sun, likely because ancient Egyptians observed wild baboons sitting with their front paws raised towards the sun at dawn to warm them. This posture, combined with their vocalizations, may have seemed as if the baboons were worshipping the rising sun. Hedj-wer is just one of several ancient Egyptian deities who could take the form of a baboon, or a baboon-headed human. In later times, the baboon became linked with Thoth (Figure 22), a deity associated with wisdom, the scribal profession, and the moon. One of the four sons of Horus, Hapy, a funerary deity whose image can be seen on the lids of canopic jars, also takes the form of a baboon. Another minor deity, Baba, is also shown as a baboon.

Offering Tables

The new loan from the Penn Museum includes two small offering tables, which may, in fact, be models of actual tables, since both examples are significantly smaller than the tables typically found in Egyptian tombs. In a tomb chapel, the spirit, or ka, of the deceased could magically receive nourishment from the representations of food and drink that sometimes decorated these offering tables. Some contained basins for offering liquids, and many are inscribed with funerary prayers requesting offerings. Typically, offering tables were positioned in front of the false door in the tomb chapel.

The calcite offering table (Figure 23) belonged to an important official named Meni, who served as a nomarch (governor). It was found at the important provincial site of Dendereh (the same site where the stela of Bebi was found). The inscription on the table lists Meni’s titles and name, along with a prayer for offerings. The text reads: “May invocation offerings go forth to the sole companion, great overlord of the nome, Meni.” It has been suggested that this calcite tablet was originally placed in Meni’s burial chamber, along with other ritual objects, rather than in his above-ground public offering chapel.

Figure 23. Calcite offering table of the nomarch Meni, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 6, 2350–2170 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E3615).

The prayer on the other small limestone table (Figure 24) mentions the funerary deities Osiris and Anubis, and requests 1000 of bread, beer, cattle, fowl, and linen for the ka (life force or spirit) of a man named Idnu, whose mother’s name was Iuehu. This is followed by offerings for a woman, perhaps a relative, named Hennut, whose mother was Ankhespepi. Both tables feature the hetep hieroglyph, which means “offering,” and depicts a loaf of bread on a mat. The two small rectangular depressions would have been used for liquid offerings on a full-sized offering table.

Figure 24. Limestone offering table of Idnu, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 6, 2350–2170 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, 54-33-3).

Figure 25. Limestone canopic jar and lid from Dra abu el Naga, Thebes, Egypt, Late New Kingdom, Dynasties 19–20, 1292–1075 BCE (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, 29-87-516A&B).

Canopic Jar

During the mummification process, embalming priests removed the intestines, liver, lungs, and stomach of the deceased, mummifying them separately. The wrapped organs were then placed in four canopic jars. Often these four jars were then placed within a canopic chest and were put in the burial chamber adjacent to the coffin. Initially, the jars had plain lids, but over time, it became common for each jar to have a lid shaped like a human head.

Eventually, the lids were adorned with representations of the four sons of the god Horus. On the the jar on loan from the Penn Museum, Duamutef, one of the sons, is portrayed as a god with the head of a jackal (Figure 25). This canopic jar was found at the site of Dra abu el-Naga. Located on the west bank of the Nile near Thebes, Dra abu el-Naga is an important non-royal cemetery site. From 1921 to 1923, Penn Museum archaeologist Clarence Fisher excavated here, focusing on the tombs of New Kingdom (1539–1075 BCE) officials. The Penn Museum houses thousands of artifacts including statuary, ceramics, funerary goods, and relief fragments from these excavations. In the Egyptian gallery at Glencairn Museum, this canopic jar is displayed alongside four faience amulets from the Glencairn collection representing the four sons of Horus (Figure 26).

Figure 26. Canopic jar on loan from the Penn Museum together with faience amulets representing the four sons of Horus from the Glencairn Museum collection: Imsety, Hapy, Qebehsenuef and Duamutef (Penn Museum, 29-87-516A&B, Glencairn Museum, E446–449).

This exciting collaboration between Glencairn Museum and the Penn Museum not only enhances Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery, but also embodies the shared mission of museums to foster education and cultural exchange. With the selected artifacts from this new loan from the Penn Museum, Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian display is enhanced, and we can further explore the significance of ancient funerary traditions. Each object helps provide valuable insight into the spiritual practices and artistic expression of the ancient Egyptians. By displaying these artifacts and investigating their meaning, we can foster a deeper understanding of history and our shared humanity. As Glencairn Museum continues to collaborate with other institutions, this partnership promises to inspire further discoveries and connections, ensuring that the legacy of ancient Egypt remains vibrant and accessible for future generations.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Bibliography

Fischer, Henry George. Dendera In the Third Millennium B.C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt. Locust Valley, N.Y.: J. J. Augustin, 1968.

Lembke, Katja, and Bettina Schmitz. Giza: Am Fuss Der Grossen Pyramiden: Katalog Zur Sonderausstellung.Hildesheim: Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum, 2011.

Martin, Geoffrey Thorndike. Umm el-Qaab. 7, Private stelae of the early Dynastic period from the royal cemetery at Abydos. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2011.

Patch, Diana Craig., et al. Dawn of Egyptian art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Distributed by Yale University Press, 2011.

Romano, David., et al. Catalogue of the classical collections of the Glencairn Museum, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. Bryn Athyn, PA.: Glencairn Museum, 1999.

Romano, Irene Bald. “No Longer the ‘Pitcairn Nike.’” Expedition Magazine 39, no. 3 (November, 1997). Accessed August 28, 2024.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.