Glencairn Museum News | Number 5, 2024

Karen Loccisano and R. Michael Palan of Bridgewater, New Jersey, contributed a Nativity called Elegance of Spirit to Glencairn Museum’s 2024 World Nativities exhibition. It is dedicated to their friend, Linda Weller, who passed away in 2023.

The first World Nativities exhibition at Glencairn Museum was in 2009. Since then, it has become a cherished annual tradition. For many Christians, the birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem offers a powerful visual symbol for the Christmas season. The representation of the Holy Family, together with shepherds, wise men, and animals at the manger, has been reimagined by artists around the world, who adapt it to express their unique personal and cultural perspectives. This year’s exhibition features 57 Nativity sets from 31 countries.

Nativity scenes traditionally weave together elements from two different biblical accounts of Christ’s birth. For example, while the Magi (Wise Men) are described only in the Gospel of Matthew, and the shepherds only in the Gospel of Luke, most depictions include both groups alongside the Holy Family and the manger. Since the biblical narratives provide limited visual detail, artists often draw on non-biblical texts produced by early Christian writers to enrich the scene—such as the addition of elements like the ox and donkey, now commonly seen in Nativity art. Many artists also add their own imaginative touches to the Nativity tradition.

Figure 1. Karen Loccisano crafted from paper clay the Holy Family and angels for Elegance of Spirit.

Karen Loccisano and R. Michael Palan of Bridgewater, New Jersey, have over 20 years of experience designing Christmas ornaments for the Kurt S. Adler Company in New York City. They have also worked as illustrators for Highlights magazine and other children’s publications. For the past 13 years, the husband-and-wife team has focused their creativity on designing handcrafted Nativities. Their first Nativity, titled American Presepio, debuted in the World Nativities exhibition in 2013. Since then, Glencairn Museum has had the privilege of exhibiting five more of their Nativities.

This year, World Nativities features their newest creation, Elegance of Spirit (photo above, Figure 1). Made of cork and paper clay, this Nativity is a tribute to their friend, Linda Weller, who passed away in 2023. The artists have shared the following reflection on their inspiration and process:

“Our goal for this Nativity was to capture the ‘Elegance of Spirit’ of our dear friend Linda Weller, who we lost to cancer this past year. We are pleased that our work is displayed under Linda’s grandfather’s Moravian Star, which was gifted to Glencairn the same year we exhibited our first Nativity here. The cathedral represents the thin space between heaven and earth, where the spiritual and physical worlds join hands. Its spires reach to the sky and point the way to heaven, bringing us closer to the divine. Karen thought of Linda Weller’s illustrations while working on the figures. Linda was a gracious and beautifully creative artist with an eye for the human and natural world around her. The two angels kneeling on either side of the Holy Family were made by Karen to resemble Linda.”

This year, for the first time, the World Nativities exhibition includes a Nativity from Armenia. It was commissioned by Anna Akhobadze, a student at Lower Moreland High School and a member of the Armenian Church Youth Organization of America at Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania. Akhobadze felt strongly that the Nativity should be made in Armenia, supporting an Armenian artist. The figures were made in Gyumri, a city in Armenia, by ceramicist Gohar Petrosyan, an artist selected for her exceptional ability to depict traditional Armenian culture (Figure 2).

Figure 2. This Nativity scene, created in 2024 by Armenian ceramicist Gohar Petrosyan, depicts the Adoration of the Shepherds. In keeping with medieval Armenian tradition, the scene takes place in a cave rather than a stable. The infant Jesus is at the center, surrounded by Mary, Joseph, and the shepherds. On loan from the Armenian Church Youth Organization of America, Cheltenham, Pennsylvania.

According to Akhobadze, “I first learned about Glencairn Museum a couple of years ago when I visited the World Nativities exhibition in 2021 with my cousin. Out of so many beautiful pieces, I failed to find one representing the first Christian nation, Armenia. This year I took the initiative to reach out to the museum and ask if they would like to add an Armenian Nativity scene. My idea was welcomed by the exhibition curators, Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal, and I started my search for the best way to present it.”

Figure 3. Anna Akhobadze poses with the Nativity scene she commissioned from Armenian ceramicist Gohar Petrosyan for Glencairn Museum’s World Nativities exhibition. Akhobadze is a student at Lower Moreland High School and a member of the Armenian Church Youth Organization of America at Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania.

The Nativity, created by Petrosyan in 2024, depicts the Adoration of the Shepherds. The work was inspired by a 1262 Gospel illumination by renowned Armenian artist T’oros Roslin (see Walters Ms. W.539, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore). The inscription on the manuscript page references Luke 2:16: “So they hurried off and found Mary and Joseph, and the baby, who was lying in the manger.” Petrosyan’s interpretation of this 13th-century illumination shows the enduring connection between medieval Armenian religious art and contemporary artistic expressions.

Figure 4. Gohar Petrosyan was born and raised in Gyumri, a city in Armenia. She had her first solo exhibition at the age of 14, and later studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts of Armenia and the Yerevan Academy of Fine Arts, earning a degree in painting. In 2015, Petrosyan set up a pottery kiln and started to focus on pottery production.

Figure 5. On Sunday, December 8, 71 parishioners from the Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania, visited Glencairn Museum following their church service. In this photo, Anna Akhobadze addresses the group, sharing insights about her project to commission an Armenian Nativity for the Museum’s World Nativities exhibition.

Figure 6. Rev. Fr. Hakob Gevorgyan, pastor of Holy Trinity Church in Cheltenham, addresses a group from the church in Glencairn’s Great Hall on December 8. The reverend was born in the village of Khor Virab, located in the Ararat region of Armenia.

A Ukrainian-themed Nativity was created for World Nativities this year by Andrij and Luba Chornodolsky of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania (Figures 7–9). Traditional Ukrainian attire was crafted for the figures by Lydia Dychdala. For 20 years, the Chornodolskys have dedicated themselves to preserving Ukrainian culture by creating immersive dioramas that showcase children’s stories and religious traditions, including Christmas and Easter. In the fall of 2024, they created and curated Ukrainian Folk Tales and Traditions for Children: A Diorama Exhibition, on the campus of the Sisters of St. Basil the Great in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania.

Figure 7. A Ukrainian-themed Nativity was created in 2024 by Andrij and Luba Chornodolsky of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, with traditional attire crafted by Lydia Dychdala.

According to Andrij, “The reenactment of the birth of Christ is found in the traditions of Ukraine going back to the earliest times after the Christianization of Ukraine in 988. The original Christmas-related rituals were all based on the winter solstice practices of paganism. Religious songs proclaiming the birth of Christ were intertwined with past pagan songs. The practice of visiting homes with caroling and storytelling relating to the birth of Christ incorporated clothing and scenes from the biblical retellings including prophets, the wise men, shepherds, and Herod, who sought to kill the Christ Child. Also, animal costumes were part of the caroling group in reverence to the importance of animals in people’s lives, but also, because the Bible tells us that when Jesus was born in the manger, animals were present.”

Figure 8. Traditional attire for Mary and the Christ Child was crafted for the Ukrainian-themed Nativity by Lydia Dychdala.

Figure 9. Traditional attire for Joseph was crafted for the Ukrainian-themed Nativity by Lydia Dychdala.

Figure 10: Luba and Andrij Chornodolsky of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, pose with a map of Ukraine they created with traditional folk art elements at the Ukrainian Educational and Cultural Center in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania.

On loan to World Nativities from the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University is an eight-foot-tall, multi-tiered German Christmas pyramid (Weihnachtspyramide) crafted by Max Boehm from 1917 to 1947 (Figures 11–12). Boehm was born in Saxony, Germany, but emigrated to the United States in 1924—bringing along with him two wooden boxes filled with the pyramid’s many components.

Figure 11. An eight-foot-tall, multi-tiered German Christmas pyramid (Weihnachtspyramide) was crafted by Max Boehm from 1917 to 1947.

Boehm created the hundreds of wooden pieces that form the multi-tiered structure, which has a rotating central spindle. Working with a jigsaw, he worked on the project during Saxony’s long winter evenings. As his son Walter recalled, “They had a lot of snow over there in the winter months. There wasn’t much to do, so they started working on their woodwork.”

After settling in New Jersey, Boehm continued to improve the pyramid. The movement, originally powered by a clockwork mechanism, was eventually upgraded with an electric motor, and the candles were replaced with electric lights. The five tiers hold 46 hand-carved figures, made by a tailor in Germany, portraying scenes from the story of Jesus Christ’s birth.

Figure 12. The five tiers of the Weihnachtspyramide hold 46 hand-carved figures, made by a tailor in Germany, portraying scenes from the story of Jesus Christ’s birth.

For the second year in a row, A.J. DiAntonio of Navidad Nativities in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, has exhibited The Grand Cartapesta Presepe in the World Nativities exhibition (Figures 13–14). In a style reflective of the Neapolitan Nativity tradition in Italy, these 200 figures from his personal collection were crafted from papier-mache from the 1940s through the 1960s. They were produced by the Italian companies Fontanini, Euromarchi, and Viviani. The Grand Cartapesta Presepe draws inspiration from the iconic “Angel Tree” and the Neapolitan Nativity scene beneath it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Following the Neapolitan tradition, the scene emphasizes the Nativity (at center) while incorporating elements of village life. On the right side, scenes depict fishermen by a stream, an encampment of Magi with camels, and a village bustling with daily activities. To the left, a Roman centurion guards the city gate, while chicken farmers collect eggs. The sounds of pipers and flutists echo along the riverbanks while shepherds watch their flocks on the hillside behind the city.

Figure 13. Overlooking the Holy Family, a heavenly host of angels from A.J. DiAntonio’s collection graces a tree adorned with vintage Christmas ornaments. The ornaments were donated to Glencairn Museum by Brother Bob Reinke, a Franciscan friar who lives in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Figure 14. Following the Neapolitan tradition, The Grand Cartapesta Presepe emphasizes the Nativity while incorporating elements of village life.

Figure 15: “Meet the Artists,” part of the World Nativities exhibition, features four Nativity artists from Ghana, Laos, Mexico, and the United States. The exhibit includes their work, portraits (some taken in their studios) and brief biographies, offering insight into their traditions and creative processes.

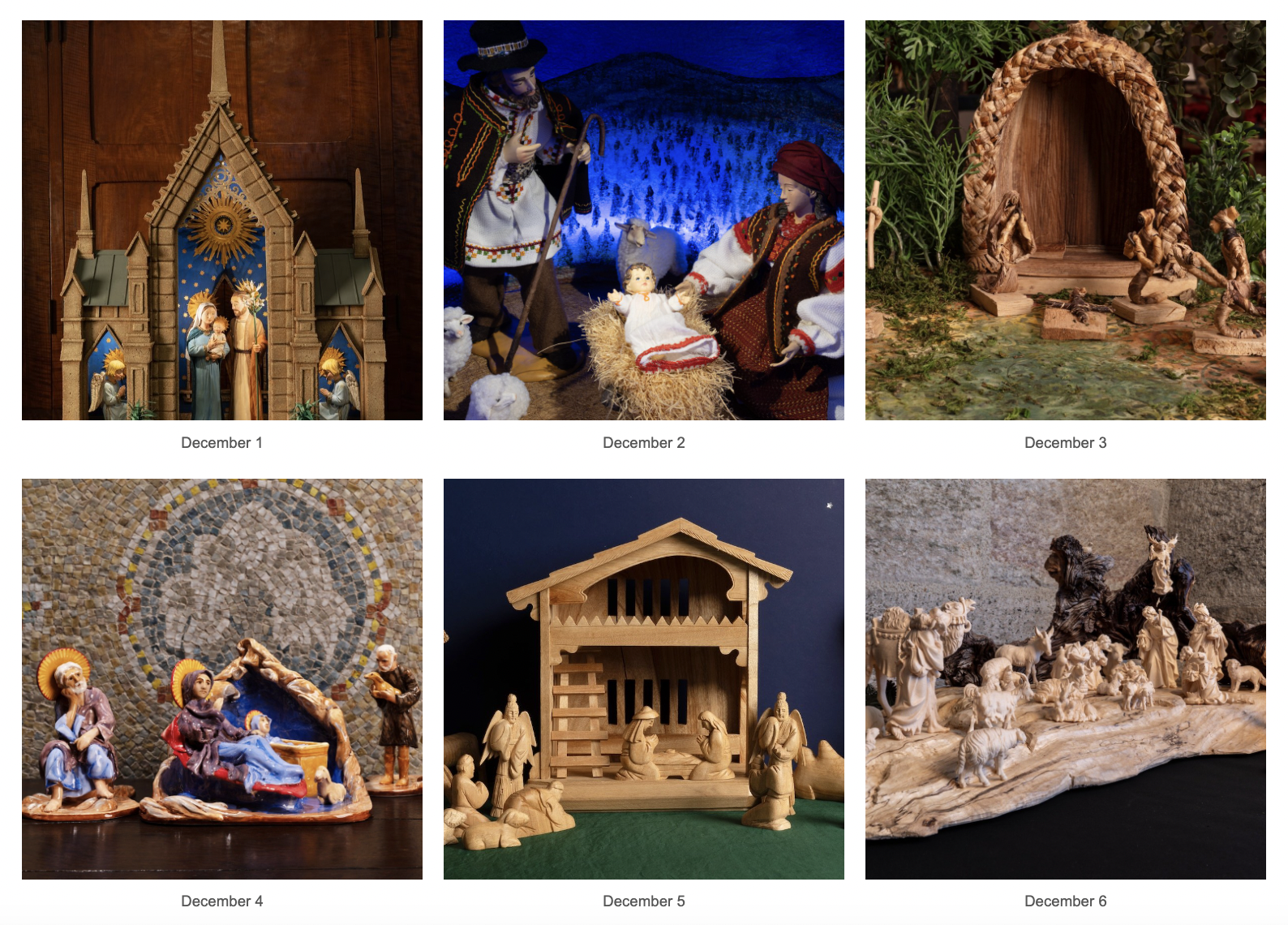

Figure 16. Every day, from December 1 through December 25, a new Nativity scene from Glencairn Museum’s 2024 World Nativities exhibition will appear in Follow the Star: A 2024 Advent Calendar. Original settings for many of the Nativities have been created by Bryn Athyn artist Kathleen Glenn Pitcairn. Follow the Museum’s social media (Facebook, Instagram) to receive each day’s Nativity in your newsfeed.

(CEG)